In May 2016, a video appeared online of a moribund chimpanzee's tender reunion with an important figure from her past. The clip shows ‘Mama’, long-time matriarch of the chimpanzee colony at Arnhem Zoo in the Netherlands, despondent in a fetal position, refusing food and water. It cuts to the arrival of Dutch primatologist and founder of the Arnhem colony, Jan van Hooff, whom Mama had known for over forty years. She recognizes him, and her features break into a broad grin. She offers weak greeting vocalizations and draws in Van Hooff to stroke his hair.Footnote 1 The encounter aired on Dutch national television and has been viewed by millions on YouTube. Commentators appreciated Mama's quasi-human behaviour, her ‘ecstatic grin’ as she cradles Van Hooff's head and ‘drums her fingers gently on his crown’.Footnote 2 Frans de Waal, Van Hooff's first doctoral student and renowned primatologist, used this touching hominid embrace in his book Mama's Last Hug (2019) to support his claim ‘that a gesture that looks quintessentially human is in fact a general primate pattern’.Footnote 3

This video reminds us of the ongoing emotional and cultural resonance of the faces and gestures of our closest relatives which reach us most importantly through documentary footage, a key medium of science communication. Van Hooff's status as a once-leading expert on primate facial displays and centrality to the story of Mama directs our attention back to London Zoo in the early 1960s, where his research began in a collaboration between Britain's new commercial television service (Independent Television, or ITV) and the Zoological Society of London (ZSL). In 1956 Granada TV – one of the companies producing content for ITV – and the ZSL jointly set up a television and film unit in the grounds of the zoo. Under the aegis of its first director, the zoologist Desmond Morris, the Granada unit became a hub for communicating ethology, the self-proclaimed ‘objective’ science of animal behaviour, through film and television. Van Hooff's research on primate facial expressions in the early 1960s instantiated two shifts emphasized by Dutch ethologist Gerard Baerends in his closing remarks to the 8th International Ethological Congress in 1963: the increasingly common practice of presenting animal behaviour in the ‘palatable … form of films’, and the growth of ‘descriptive papers and films … on mammals’ relative to those on insects, fishes and birds.Footnote 4

Historians have reconstructed uses of the moving image as an analytical tool and communication device in ethology's canonical research programmes. Film served the public promotion and legitimation of Konrad Lorenz's work on imprinting and that of Karl von Frisch on honeybee communication.Footnote 5 For Nikolaas Tinbergen, it was a crucial aid for comparing the behavioural adaptations of gull species to ecological niches.Footnote 6 By the 1960s animal behaviour researchers commonly collaborated with television producers in what Jean-Baptiste Gouyon described as ‘mutual exploitation’.Footnote 7 The former had scientific expertise and authority; the latter had funds, broadcasting acumen and a large audience. Both benefited from arrangements that were nonetheless sometimes fraught. Building on this work, I introduce two new themes: first, the importance of film in the extension of ethology to primates; and second, the significance of commercial television as an unstudied player in the history of science and the moving image. I find that, through its unit at the zoo, Granada sponsored innovative research by an up-and-coming ethologist. It produced a television film on the evolution and function of facial expressions based on Van Hooff's research on captive primates. This was mutually advantageous: Van Hooff obtained a valuable reel which he used to analyse behaviour sequences, present at conferences and extract stills for publication; Granada gained a telegenic programme authorized by ethological expertise which applied to nonhuman primates rules of shot composition normally used to focus attention on human faces on television.

The Granada TV–Zoological Society of London Film Unit has received scant attention from historians, mentioned in passing in narratives of the BBC, but never examined in its own right.Footnote 8 This reflects a broader bias towards the BBC in the burgeoning histories of science on UK television.Footnote 9 The dearth of research on ITV stems from the lesser prestige of a network more associated with light entertainment than with serious programming, a sprawling and shifting regional structure inhibiting archival preservation, and the inaccessibility to researchers of surviving written materials.Footnote 10 As a joint venture the Granada unit presents a golden opportunity to sidestep this empirical impasse using the rich archives of the ZSL and of its secretary, Solly Zuckerman. Together with the fortuitous survival of the Van Hooff programme, one of the few unit films preserved in the ITV Archive, these materials can tell us much about how the ‘zoological–entertainment complex’ functioned in ITV's largest and longest-running company.Footnote 11 This article also shows that commercial television, like its licence-fee-funded counterpart, was an important source of financial, material and technical patronage for ethologists in the 1960s.

Primate facial expressions and the challenge of ethology

For the first sixty years of the twentieth century, facial-expressions research was replete with comments about the utility and desirability of motion picture records, but largely devoid of films.Footnote 12 This practical neglect was in part a legacy of the definition of facial expressions as scientific objects in the second half of the nineteenth century. The photographic practices of Duchenne de Bologne, Oscar Rejlander and Charles Darwin ensured that ‘the particular instant captured by photography defined and identified how … expressions appeared’.Footnote 13 In other words, a facial emotion was constituted by a single photograph of an expression either ‘held’, as in the galvanic experiments of Duchenne or, later, captured by the instantaneous process.

Much like Darwin's research for The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals (1872), the locus classicus of modern expressions studies, twentieth-century psychologists used photographic portraits to address two basic questions: were expressions inherited or acquired, and how accurately could observers identify them?Footnote 14 Some photographic series, notably that of French psychoanalyst Jean Frois-Wittmann made in 1930, became canonical in recognition experiments.Footnote 15 For primate researchers, photographs of an infant chimpanzee produced by Russian comparative psychologist Nadia Kohts and her husband Alexander in the 1910s were similarly influential. While valued for their quality – for example, by Ada and Robert Yerkes, the doyens of early twentieth-century great-apes research – static photographs left much to be desired. In The Great Apes (1929), the couple noted that photography ‘incompletely represented the affective life’ and that a ‘nearer approach to adequacy of representation may be obtained by the simultaneous use of motion picture film and phonographic record … to represent action and to give the observer the “feel” of an affective episode’.Footnote 16 This exemplifies a tendency, common to primate research and experimental psychology, to idealize but not use moving images in the study of facial expressions, probably reflecting the lower cost and convenience of producing and reproducing photographs instead.Footnote 17

By contrast, ape faces were seen in cinemas, most iconically the bestial stop-motion animation face of King Kong. This 1933 Hollywood classic tapped into nineteenth-century imagery of the gorilla's atavistic brutality perpetuated in a pervasive Darwinian iconography of simianized people and humanized apes.Footnote 18 Kong's face gave powerful cinematic form to an older trope of apish savagery. Another perennial convention, operating in a different emotional register, was to exploit primates for comedy. London Zoo's chimps’ tea party was among its most popular summer attractions between the late 1920s and the early 1970s, and was imitated by zoos around the world.

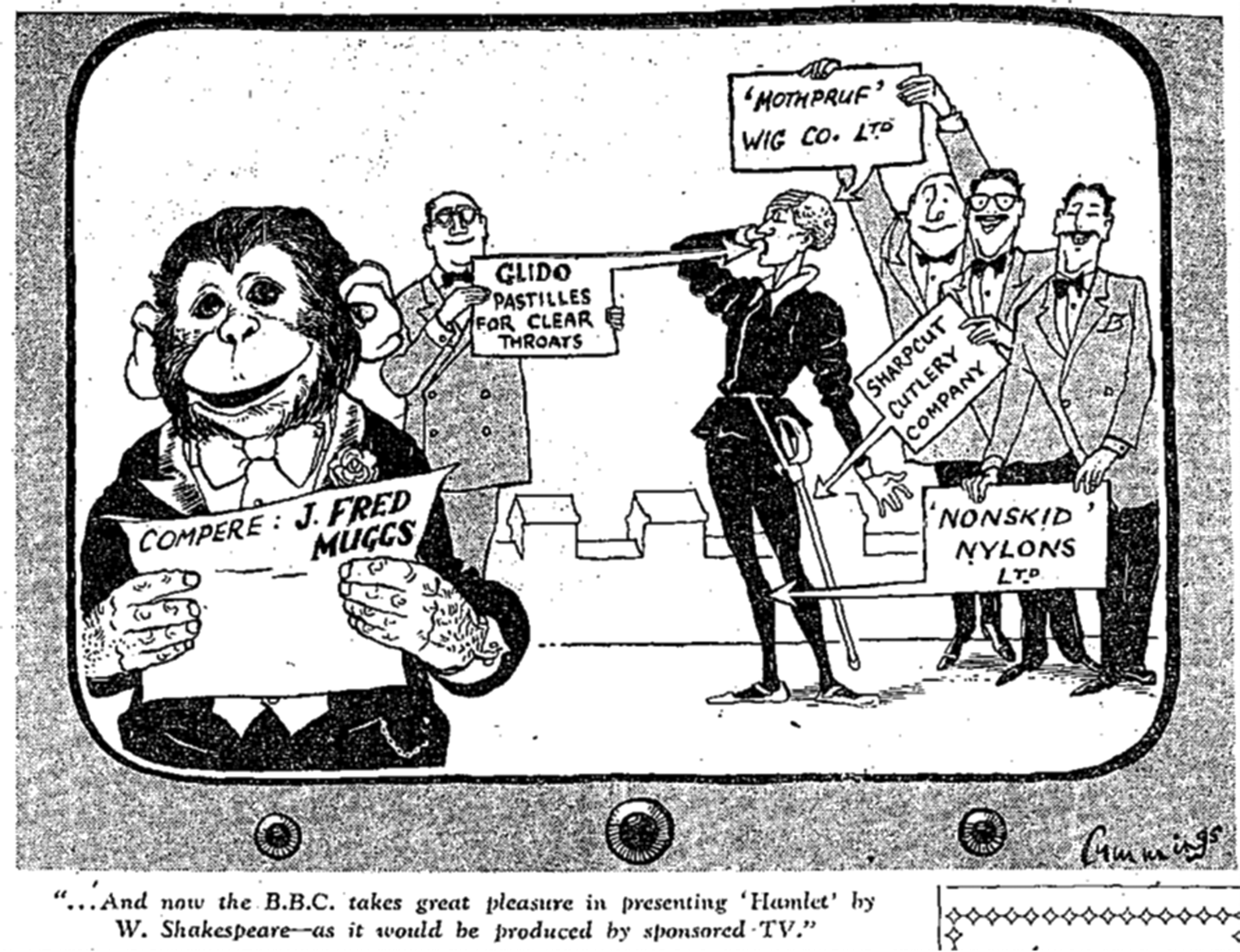

This status of chimps as comedy turns became a flashpoint in arguments about introducing commercial television in Britain. In the early 1950s, when Parliament debated the possibility of an advertisement-funded service, impish photographs and cartoons of J. Fred Muggs – an infant chimpanzee named, no doubt, in reference to his expressive face – peppered the press. Muggs served as ‘mascot’ to Today, the morning chat show of the major US commercial broadcaster NBC. When Today covered the coronation of Elizabeth II, Muggs was in the studio dressed in a kilt. For detractors in Britain, this juxtaposition of Muggs and monarchy was a cautionary tale of the irreverent ‘vulgarity’ of advertisement-funded television. Leading the attack was the Daily Express, owned by press baron and rabid opponent of commercial television Lord Beaverbrook, which ran a satirical cartoon envisioning how such a service would treat a production of Hamlet, complete with Muggs as compere (Figure 1). Critics were soon vindicated: in 1956, PG Tips's parent company Brooke Bond capitalized on the popularity of London's chimps’ tea party to launch a successful television advertising campaign. Facial movements and dubbed voices gave the illusion of a chatty family of hapless chimps in human clothes sipping cuppas. Imbricated in consumer culture, moving images of apes were used to thrill, frighten, peddle and amuse. Ethologists studying primates in the 1960s made this rich iconography a polemical target as they promoted alternative understandings of monkeys and apes grounded, they maintained, in objective scientific methods that included film.Footnote 19

Figure 1. A cartoon satirizing ‘sponsored TV’, the prevailing US model of commercial broadcasting which gave advertisers direct control over programme content, by imagining a BBC production of Hamlet in which smarmy salesmen advertise the Hamlet actor's accoutrements while Muggs comperes in the foreground. The accompanying article in the middle-market Daily Express describes Muggs's Today role as ‘to make funny faces’. Michael Cummings, Daily Express, 10 June 1953, p. 4. © Cummings/Express/Mirrorpix.

A handful of zoologists in the UK, the United States, the Netherlands and South Africa began studying primate facial expressions around 1960. Since primates were challenging and expensive to keep, collections concentrated in zoological gardens, university departments and medical schools. The Cambridge Sub-department of Animal Behaviour, Yale Department of Zoology, the University of the Witwatersrand, Bronx Zoo and London Zoo: these were the key sites for early primate expressions work. A variety of intellectual and disciplinary concerns motivated practitioners. Niels Bolwig was guided by his senior colleague at Witwatersrand, Raymond Dart, to treat primate behaviour as a lens through which to understand human evolution.Footnote 20 Cambridge ethologist Robert Hinde established a rhesus monkey colony in 1959 to investigate his friend John Bowlby's attachment theory using primate models.Footnote 21 That year, Hinde's doctoral student Richard Andrew moved to Yale to pursue the evolution of human laughter by studying primate communication.Footnote 22

All of these researchers had some access to cine cameras, but financial and practical hurdles impeded the serious use of celluloid. Cambridge ethologists had to shoot sparingly because of prohibitive film stock costs.Footnote 23 Academics at Witwatersrand had the added problem of frequent loss or damage during processing and copying.Footnote 24 Yale Zoology had ‘no facilities for motion picture processing and editing, and … enlarging and printing [facilities which] can only be described as primitive’.Footnote 25 The resources for high-volume shooting and professional editing rested with television companies, a critical source of funding and expertise for the production of scientific films in this period. This science–television nexus provided the enabling conditions for Jan van Hooff's research.

Primate ethology at London Zoo

Van Hooff took an idiosyncratic path to his topic and to London Zoo, one of the largest primate collections in the world and well networked with academic ethology. Son of the director of Burgers’ Zoo in Arnhem, Reinier van Hooff, and grandson of its founder, Johan Burgers, Jan van Hooff grew up alongside a rich menagerie of animal life. He studied biology at Utrecht University, where a physiology-heavy curriculum offered little scope to develop his enthusiasm for living organisms. Van Hooff remembers encountering ethology towards the end of his degree – principally in the writings of Nikolaas Tinbergen and Konrad Lorenz – while working briefly in 1958 as research assistant to the retired psychologist Frederik Buytendijk.Footnote 26 Van Hooff stayed at Utrecht to work towards his doctoraalexamen – the Dutch equivalent of a master's degree which for biologists required a series of research projects in different areas of biology. Captivated by the work of his compatriot Tinbergen in Oxford, Van Hooff was determined to do one project in ethology. His intimate knowledge of zoo primates and other animals, and his undergraduate reading of Darwin's Expression of the Emotions, help explain his decision to specialize in facial expressions.

Van Hooff's supervisor, Sven Dijkgraaf, himself a student of pioneering ethologist Karl von Frisch and an expert in sensory physiology, asked his friend Tinbergen if Van Hooff could visit Oxford. The timing was propitious, with Tinbergen himself musing upon facial expressions around this time. Throughout the 1950s, Tinbergen and his students had conducted field studies comparing the behaviour of gull species. The aim was to determine the function, causation and, ultimately, origins and divergence of displays. In addition, Tinbergen sought to stimulate further comparative ethological research by calling ‘attention to some ideas which might be checked in other animals’.Footnote 27 He wondered, for instance, whether human smiling and laughter had an appeasement function analogous to displays he had studied in black-headed gulls.Footnote 28 So Tinbergen must have been excited to read Dijkgraaf's letter. He agreed to supervise Van Hooff on condition that, in the absence of suitable primate facilities in Oxford, Van Hooff base himself at London Zoo under the day-to-day oversight of Tinbergen's former DPhil student, Desmond Morris. The zoo's curator of mammals, Morris was also famed on the small screen as ITV's ‘zoo man’ and an expert on chimp behaviour.

Van Hooff reached London in August 1960. Funded by his master's scholarship and his parents’ purse, he stayed through the following spring, and returned for seven months between September 1961 and April 1962.Footnote 29 Doctoral students in ethology tended to work on a single species, compiling an ‘ethogram’ or full inventory of movements involved in a category of behaviour, such as courtship or fighting.Footnote 30 Van Hooff, by contrast, began a bolder comparative study spanning dozens of primate species while still a master's student, a sacrifice of depth for breadth suggested by Morris. This would have been impossible had Van Hooff already been enrolled on a conventionally specialized doctorate. It was facilitated by Morris's freedom to supervise projects that university ethologists might have regarded as maverick or overambitious, and his possession of the curatorial power to give Van Hooff an office and full access to the Monkey House, and to ensure the cooperation of keepers and staff.

London Zoo boasted all four genera of anthropoid ape – gorillas, chimpanzees, orangutans, and gibbons – numerous Old World monkeys, and a smaller assemblage of New World species. The organization of the Monkey House, which accommodated similar species adjacently, facilitated the comparative approach that Tinbergen encouraged. Van Hooff could let his gaze flit between cages, speculating on phylogenetic relations while doing his primary work of describing and cataloguing expressions.Footnote 31 This day-to-day practice comprised observation and intervention and centred on interactions between two members of the same species. Often, Van Hooff would introduce conspecifics unfamiliar with one another and study their subsequent facial and bodily movements. Other experimental interventions included mimicking expressions himself to elicit responses and showing an individual its own face in a mirror. In each case, Van Hooff would record the succession of expressions and behaviours using, at least in the first months of his work, a humble notebook, which he filled with a shorthand developed in consultation with Tinbergen.

Conceptually, Van Hooff analysed facial movements into an integrated hierarchy of ‘facial elements’: the eyes, eyelids, eyebrows and upper head skin, ears, mouth-corners, and lips. Van Hooff proposed that each facial element could occupy one of several positions, which he called ‘expression elements’ – the eyebrows could be raised or lowered, for example, or the eyes be ‘glancing evasively’. Finally, he maintained that different combinations of these expression elements could form ‘compound facial expressions’, with sums greater than their parts.Footnote 32

Between Regent's Park and Oxford, Van Hooff found fertile ground for his ethology. Tinbergen supported a project that answered his calls for comparative studies on new species and his specific interest in the phylogeny of human facial expressions. Morris provided access to extensive primate collections and the freedom to work on an innovative project. Van Hooff applied the methods of comparative ethology to new species and patterns of movement, thereby establishing expertise at the outset of his academic career. Yet without Granada, this might have come to little, and so it mattered that Van Hooff offered more than expertise.

Newsworthy research serves Granada

Broadcasters seized on Van Hooff, a charismatic, dapper Dutchman with a compelling research topic. Two months after arriving at London Zoo, in the second week of November 1960, the BBC and ITV covered Van Hooff's research. His flair for communication, coupled with staple broadcasting techniques, made for memorable performances. On the BBC, Cliff Michelmore, the ‘John Bull’ of the small screen, interviewed him for the current affairs programme Tonight. The discussion was punctuated by blown-up photographs of primate faces which added visual interest and allowed Van Hooff to decipher the expressions to an audience of seven million.Footnote 33 Van Hooff's ITV appearance can be reconstructed using a remarkable set of photographs taken in Desmond and Ramona Morris's Primrose Hill flat showing the interview as it was transmitted on their television (Figure 2). Cutting from a frontal two-shot (Van Hooff talking to interviewer) to close-ups allowed Van Hooff to enact amusing ‘monkey faces’ – soon his party piece – to the evident delight of the Morrises. Performing a repertoire of mimicked expressions, whether to the cameras, to primates behind chain-link enclosure fences or at dinner parties, was a form of embodied scientific practice which functioned variously as experiment, aid to scientific communication and visual gag.Footnote 34 The appeal of Van Hooff's topic and television appearances led to further media coverage: in British newspapers and magazines, radio interviews and US papers, which reported on the Dutchman who ‘mugs at monkeys’ in London Zoo.Footnote 35 Printed, aural and visual media fed off each other in creating scientific news.

Figure 2. Jan van Hooff interviewed on ITV. (a) Van Hooff (right) with unidentified interviewer (left). (b) The Morrises laugh as they watch Van Hooff's contorting face on their seventeen-inch Murphy television set. Photographs courtesy of Desmond Morris.

By January 1961, Van Hooff's research had been earmarked as a possible programme topic by the Granada TV–Zoological Society Film Unit. Set up as a joint venture in January 1956, the unit made television programmes and scientific films about animal behaviour using the ZSL's collections. During its seven years of operation, the unit produced eight television series, most memorably the flagship children's weekly Zoo Time, which at its peak of over three million viewers outcompeted all but one of the BBC's five natural history programmes.Footnote 36 A focus on captive animals, shot in their enclosures or in Granada's purpose-built zoo studios, was in marked contrast to the wild fauna typically shown on the BBC.Footnote 37 It also differentiated Van Hooff's research from the lush tropical aesthetic of contemporaneous field primatology. Characterized by long-term projects, often conducted by female researchers and supported by National Geographic, these highly mediatized studies of free-living apes created a ‘primate folklore for the modern age’, and made icons of researchers and research subjects alike.Footnote 38 Working in captivity may have lacked the aura of the field, but it facilitated Van Hooff's controlled observations and comparative practice. And while not propelling him into the pantheon of ‘primate folklore’, the Granada unit repeatedly gave Van Hooff a mass UK audience.

In the early 1960s, ITV companies were subjected to intense scrutiny by the Pilkington Committee, formed in 1960 to ‘consider the future of the broadcasting services in the United Kingdom’ and recommend whether a planned third channel be allocated to the BBC or commercial television.Footnote 39 Pilkington became a byword for establishment-pleasing television. Commercial broadcasters, critics charged, eschewed public-service obligations and reaped fantastic profits by flooding their schedules with cheap quiz shows and American imports. ‘Balance’ was the watchword of the Pilkington discourse and its report, published in 1962. Broadcasters had an obligation to produce schedules that struck a balance between light entertainment and serious programmes, although those terms never gained binding definitions.

Historians have shown how, in this context, current-affairs programmes including Granada's flagship World in Action became ‘premium products’ for ITV.Footnote 40 Natural history programmes acquired similar value. Sunday Times television critic Maurice Wiggin extolled Another World, a Granada series about wildlife in Borneo, as ‘pure Pilkington, a work of quality to delight both the innocent and the sophisticated’.Footnote 41 For L. Marsland Gander, reviewing Animal Story, the Granada unit's first adult series, in the Telegraph, ‘Surely it is folly to utter sweeping denunciations of television in all its forms when it can offer programmes such as this’.Footnote 42 Gander reserved his ‘highest praise’ for an early episode of Anglia TV's Survival, a wildlife series with a conservation message, and wondered whether general programming improvements were ‘because of Pilkington influence’.Footnote 43

Against this backdrop the Granada unit began working on a new series, eventually titled Breakthrough, and, no doubt encouraged by Morris, decided in January 1961 ‘that the young Dutch zoologist, Van Ho[o]ff, who has been working on animal facial expressions, should be contacted for some advice’.Footnote 44 By March, two programmes with Van Hooff were planned: one on facial expressions, and another, later dropped, on a side project with Morris on conflict avoidance and appeasement behaviours.Footnote 45 At this stage, the films were intended for a new run of Animal Story, but in October 1961 this idea was abandoned and the ‘material (in part) re-grouped into another series, tentatively called “Breakthrough”’.Footnote 46 This would comprise seven episodes on two themes: patterns of behaviour involved in courtship and parenting, and the nature of vision and visual communication (including ‘Animal expressions’). This abrupt and important change goes unexplained in the minutes of the unit's monthly policy meetings. The first two Animal Story series had been critical successes, even pulling an award at the 1959 Venice Film Festival. Why rebrand the material and reconceptualize the series? One possibility lies with the figure of Denis Forman, Granada's de facto head of programmes, who kept a close watch on the unit's productions. In June 1961, Forman told Douglas Fisher, the unit's erstwhile director of photography, of his dissatisfaction with the disjointed ‘scrapbook’ approach of most natural history programmes, including Animal Story. Instead, Forman confided, his ideal series would be cohesive, developing a ‘thesis’ over its episodes as the work of an ‘editorial mind’.Footnote 47 Since the policy shift occurred soon after this intervention, in summer 1961, Forman could have catalysed the attempt to create a more coherent series.

By March 1962, when filming for ‘Animal expressions’ was complete and Van Hooff's research stint at the zoo was drawing to a close, Granada recorded him for three episodes of Zoo Time transmitted that May and June. Together with Morris and Malcolm Lyall-Watson, Morris's second ethology supervisee, Van Hooff elicited facial expressions from chimps, rhesus monkeys, marmosets and other primate species and explained their meanings. In the second of Van Hooff's Zoo Time appearances, transmitted on 23 May, he engineered one of his stock experimental setups for the cameras: introducing two monkeys unfamiliar with one another and describing the dynamics and facial movements of ensuing interactions. A still printed in a 1966 Zoo Time book spinoff (by a Granada-owned publisher) depicts the scene (Figure 3). Held in Van Hooff's and Lyall-Watson's hands in a forced encounter, the monkeys turn their heads to avoid each other's gazes. Morris interpreted the image: ‘The picture shows … that when two young monkeys are shy about meeting they will not look one another in the face’, suggesting that by ‘studying this kind of behaviour we can learn a great deal about our own human actions’.Footnote 48 In children's programmes, books and television series for adults, Van Hooff's newsworthy research was an asset for Granada, pregnant with insights about human expressive behaviour.

Figure 3. Zoo Time production still. Van Hooff (right) and Malcolm Lyall-Watson (left) introduce two unacquainted monkeys which avoid each other's gazes while Morris (centre) comments. From Desmond Morris, Zoo Time, London: Rupert Hart-Davis, 1966, p. 129.

‘Animal expressions’ and television cultures of the face

Having reached Granada's large weekly children's television audience in spring, Van Hooff's research went out to adults that autumn. Unusually for an episode other than a series opener, Granada gave ‘Animal expressions’ full-page billing in the TV Times. Readers flicking through would have been struck by the prominent image of an orangutan cupping its protruding lips; the headline, ‘breakthrough to … the mind of a monkey’, tantalized with the promise of interspecies understanding. Cognitive authority was grounded in the person of Van Hooff, the ‘dignified Dutchman’, who had spent ‘over two years’ working on this ‘scientific experiment’.Footnote 49 The programme would ‘tear aside people's prejudiced and sentimental ideas about animal behaviour … to show that there is a reason for it’. This invocation of hard scientific graft and expertise, together with the bellicose anti-anthropomorphism so central to the public ethology cultivated by Morris at the zoo, differentiated Breakthrough from the BBC's natural history offering, particularly its flagship Look, presented by gentleman naturalist Peter Scott. Look was a studio-based television lecture supplemented by films, usually made by amateur experts from Scott's social network who commented on their footage as it was screened. By 1961 Look's format and Scott's style seemed an amateurish ‘remnant of past times’ even to its producer, Eileen Molony.Footnote 50 Breakthrough, by sharp contrast, was a collaboration between ethologists and professional broadcasters, filmed and tightly edited for television.

‘Animal expressions’ went out at 10.45 p.m. on Tuesday 16 October 1962. The late hour is consistent with a scheduling policy advocated by the Independent Television Authority (ITA), which regulated ITV companies like Granada. Rebutting Pilkington criticism, the ITA argued that ‘serious’ ITV programmes televised late outperformed BBC equivalents during peak hours, suggesting that earlier placement was counterproductive.Footnote 51 Schedulers may also have deemed Breakthrough too specialist, and therefore unlikely to draw large audiences and advertising revenues at peak times. A twenty-six-minute running time in a thirty-minute slot suggests that ‘Animal expressions’ was bookended by four minutes of advertising (ITV rarely broke the flow of documentary programmes with internal advertisements and ‘Animal expressions’ shows no hint of the ‘natural breaks’ which signalled such intermissions).Footnote 52

The title sequence, which introduced each episode of Breakthrough, betokens a scientific treatment of animal behaviour. We see the back of an owl's head. Timpani roll in a martial rhythm.Footnote 53 The owl turns 180 degrees to face the camera with its huge black eyes in a penetrating stare. The shot fades and the eyes are replaced with the eyepieces of a microscope, inviting viewers to reverse the gaze and peer, with the aid of science, inside the enigmatic world of animal behaviour, and all the while the solemn percussion accompaniment reinforces the visuals (Figure 4). Elements of this attention-grabbing format were borrowed from Granada's current-affairs programmes.Footnote 54 Commentary was provided by Robert Holness, familiar to ITV audiences as host of the gameshow Take a Letter and one of several non-scientists Granada used to narrate its zoo programmes to broaden their appeal. As the titles faded into a close-up shot of a chimpanzee's face, Holness lent anthropological import, intoning that the expressions examined in the episode represent the involuntary kind which, ‘whether we like it or not … tell other people exactly what we are feeling’.

Figure 4. Screen shots from Breakthrough (1962) titles. The owl's eyes dissolve into the eyepieces of a microscope. The camera then pulls back while the microscope rotates and the series title appears. ITV plc.

The programme comprised a cinematic narrative of the evolution of facial expressions shaped by Van Hooff's comparative method. Opening with the ubiquitous ‘bite’ threat, the sole expression of fishes and reptiles, it turned to the complex primate facial movements which are its focus.Footnote 55 Cutting from shots of lizards in open-mouthed threat to analogous displays in hippos, wolves and foxes creates powerful visual linkages that traverse the animal kingdom and reinforce the evolutionary message. The second half of ‘Animal expressions’ is a montage of short clips showing similarities and differences in the facial displays of primates. Cutting rapidly from a sooty mangabey to a mandrill to a black ape (Celebes crested macaque), and then a moor macaque, the succession of bite threat clips mirrored Van Hooff's comparative approach in the taxonomically ordered Monkey House.

Conversely, ‘Animal expressions’ adapted the powerful filmic and televisual convention of framing human faces to Van Hooff's research topic. As pioneering television producer Norman Swallow averred in 1966, ‘The human face, caught in moments of emotion or reflection or repose, is one of the most consistently powerful of all the images presented on the television screen’.Footnote 56 In Britain, when Jasmine Bligh announced the postwar resumption of television broadcasting in 1946, the close-up of her face was ‘widely regarded as the paradigmatic televisual image’.Footnote 57 When tightly framed, the human head appeared near life-size on the small screen which, watched at head height, situated ‘expressive faces among those of the [domestic] audience’.Footnote 58 Recall, for example, the placement of Van Hooff's televised face relative to the Morrises’.

Filming monkey faces for television therefore involved adapting compositional norms established for humans, often to striking effect, as can be appreciated by analysing specific sequences. In a headshot around the fourteen-minute mark, the camera holds the face of a young crab-eating monkey (Macaca fascicularis) in focus for a full forty seconds as it shifts uncomfortably under the stare of someone offscreen (Figure 5). Television allowed viewers to gaze with peculiar intensity upon the faces of its subjects. As critic Maurice Wiggin observed, ‘the man who appears before the cameras should know that he is being stared at … Relaxed and at our ease, lolling on our own hearths, we tend to scrutinise the close-up image with merciless and unmannerly severity’.Footnote 59 This effect had been captured by the notion of ‘parasocial interaction’, introduced by Donald Horton and Richard Wohl to media psychology in 1956 for ‘the illusion of face-to-face relationship’ generated especially by television.Footnote 60 Viewers of ‘Animal expressions’, watching the crab-eater's evasive eye and head movements, may have had the uncanny sense that their own stares were responsible for the juvenile monkey's jittery behaviour. The shot re-establishes to reveal a second monkey on the right; a frontal two-shot now frames the scene, familiar to audiences from its ubiquity in early television drama and studio interview programmes.Footnote 61 These conventional framing techniques lent a familiar televisual grammar to primate facial movements. PG Tips advertisements also exploited this, but differed in their meticulous choreography, dressed-up chimps and dubbed voices.

Figure 5. Crab-eating monkey avoids a stare from behind the camera in ‘Animal expressions’ (1962). ITV plc.

Much of the imagery in ‘Animal expressions’ was emotive. One sequence shows a chimp drawing back the corners of its mouth in apparent frustration at being repeatedly offered and then denied a drink, while Holness observes that ‘for most people the sight and sound of a chimp in rage is very disturbing’. As Thomas Dixon has shown, the acceptability of intense emotional expression on television underwent an important shift around 1960.Footnote 62 When, in the late 1950s, pioneering interview-based programmes including This Is Your Life and Face-to-Face (both BBC) presented weeping for the first time, some critics excoriated what they saw as unrestrained Americanized displays. By the early 1960s, intense emotion in interview and drama programmes was becoming common and accepted.Footnote 63 The emotions that played on the faces of monkeys and apes in ‘Animal expressions’ seem to have passed without negative comment, unlike the first episode of Breakthrough, which, one viewer complained to the TV Times, included the ‘sudden appearance on the screen … of two enormous spiders, magnified to many times their natural size’.Footnote 64 Television personalities were often criticized for ‘putting it on’ or ‘playing to the cameras’. As Holness emphasized at the start of the programme, the expressions of monkeys and apes in ‘Animal expressions’, by contrast, being ‘involuntary’, were understood as authentic.

An up-and-coming producer at the BBC Natural History Unit, Jeffrey Boswall, praised Breakthrough in the same breath as books for general audiences by Lorenz and Tinbergen for showing ‘how animals can be made interesting without misrepresenting them’.Footnote 65 His language echoes television critics praising the Pilkington virtues of wildlife programmes. Granada and the ZSL retrospectively presented Breakthrough as above all a scientific achievement, and it was in their interest to do so.Footnote 66 In reality, and typically of Granada productions of the time, episodes like ‘Animal expressions’ blended seriousness and frivolity. For example, a voice-of-God commentary signalled detached authority and foregrounded scientific content over personality, yet the invisible commentator was a quiz show host. A stern percussion motif introduced each episode, but a light, quirky score accompanied the primate faces. The programme's TV Times billing stressed the objectivity of ethology, yet its imagery and tone exploited the comedic value of ‘funny faces’. This hybrid style was part and parcel of the production culture encouraged by Granada's chairman Sidney Bernstein and senior producers such as Denis Forman. A showman committed to entertaining spectacle that held television audiences’ attention, Bernstein was also bent on maintaining Granada's reputation as the leading contributor of public-service programmes to the ITV network. ‘Animal expressions’, with its judicious blend of serious televisual conventions and the lighter cultural associations of primate faces, succeeded – with its parent series Breakthrough – in the eyes of zoologists and post-Pilkington programme-makers alike.

Granada footage at a symposium on primates

If Van Hooff's research gave Granada a telegenic topic and a set of captivating performances, Granada served Van Hooff with a versatile film which he could watch and rewatch for his own research and adapt to various formats of visual communication. At conferences he projected footage of the facial movements he was categorizing and analysing; in print he had series of stills reproduced in an early, if not the first, example of this mode of representing behavioural interactions in primate ethology. Working with a television company gave Van Hooff an edge over his rivals. The Granada unit had a darkroom, a viewing suite, two cutting rooms and a professional production team on site. Allowing Van Hooff to surmount the prohibitive costs of filmmaking and lending him technical expertise, Granada's production of ‘Animal expressions’ illustrates an increasingly common alignment of broadcasters and scientists in the production and circulation of zoological films, which here gave him a competitive advantage in the study of primate facial expressions.

From the mid-1950s, the BBC had begun to operate as an important patron of zoology. In part responding to Granada's contract with the ZSL, it helped fund expeditions and research in exchange for image rights.Footnote 67 Most significantly, the BBC Natural History Unit commissioned films from Oxford zoologists, providing funds from the early 1960s that were crucial to the establishment in 1968 of Oxford Scientific Films, a leading specialist in macrophotography.Footnote 68 The Granada unit's zoological films represented a novel alignment of ethology and television production. Most footage was shot in purpose-built studios at the zoo, creating a different aesthetic from BBC productions in exotic locations. This general television–zoological nexus was well represented at an important symposium on the primates held at London Zoo on 12–14 April 1962 which attracted over four hundred conferees, including Van Hooff and several other primate ethologists.

The filmic culture of this symposium (and others like it) has gone largely unnoticed by historians more interested in its seminal status as, on the one hand, the meeting at which Jane Goodall first presented her research, and, on the other, one of three independently planned conferences in spring 1962 that reignited primate research in Europe and North America.Footnote 69 But in the recollections of attendees, moving images were among its most memorable aspects, and so deserve closer attention.Footnote 70 The symposium was organized into three themes: behaviour, functional anatomy and genetics. Film was the showpiece of two presentations in the first section on behaviour, including Van Hooff's, who projected footage that would appear in ‘Animal expressions’ that October. This chronology is significant. Granada held the copyright to all films produced by the unit, including ‘Animal expressions’, and its general policy was that ‘any lending of materials should not conflict with the selling potentialities of these films’, including public exhibition prior to transmission on television.Footnote 71 Granada must, therefore, have made a goodwill exception for Van Hooff (as it did occasionally for the ZSL), who used the footage six months before the broadcast on ITV.

Van Hooff had a thirty-minute slot in a four-person afternoon panel. He presented after Richard Andrew, who spoke on vocalizations; a complementary pairing on two sensory modalities understood to be interdependent though seldom analysed together. After tea, conferees reconvened for an hour's discussion led by Desmond Morris and the Swiss zoologist Hans Kummer. This went unrecorded, but we can assume that Morris gave his student a good hearing. Concluding remarks by Solly Zuckerman, who chaired the behaviour section, followed. Notoriously combative, Zuckerman evaluated the day's papers against his own, as he saw it, paradigmatic research of the 1930s. They fell, he claimed, into two classes: those ‘still dominated by anecdote and speculation’, and those exemplifying how ‘new scientific techniques have been applied to the subject’.Footnote 72 Van Hooff's filmic contribution fared well. Zuckerman praised the ‘detailed analysis, using precise photographic methods … of facial expressions which characterise New and Old World monkeys’.Footnote 73 This was no mean feat. Photographic and filmic evidence did not guarantee veracity for Zuckerman. One conferee, Alison Jolly, who travelled from Yale to the symposium with Andrew, her PhD adviser, remembers a moment when Zuckerman obstinately denied baboon carnivorism in the face of ‘a close-up film … of male baboons with blood-smeared muzzles and the intestines of a baby antelope dangling from their teeth’.Footnote 74 The images were, in fact, stills from a film which Raymond Dart had acquired from ‘amateurs’, as he put it, shot in Kruger.Footnote 75 The key difference for Zuckerman, who considered himself a crusader against anecdotal evidence, therefore, was probably the credibility of the filmmaker. He trusted Morris, Van Hooff and the Granada unit, but not unidentified ‘amateurs’.

The cinematic spectacle of the symposium culminated in a special film session on the final morning. While uncredited in the published proceedings, two of the five films were produced or co-produced by television companies and a third had been shown on the BBC the previous week, illustrating both how integral television production was to the resurgence of primate research in the 1960s, and how easily moving images travelled between specialist audiences and broad national ones. Morris showed a Granada film on chimpanzee behaviour, while David Attenborough displayed BBC footage of lemurs. The third film was presented by Ronald Hall, professor of psychology at Bristol University, as ‘Paradise for baboons’, a twenty-minute black-and-white film on Look, before it was projected, austerely retitled ‘The chacma baboon’, at London Zoo. While it passes without comment in the Proceedings, the television transmission was well received and the film highly rated by primatologists.Footnote 76 The crucial distinction between the films of Van Hooff and Morris, on the one hand, and those of Attenborough and Hall, on the other, was location. The bulk of the Granada unit's films were produced in the zoo, mostly in purpose-built studios. This could lend them what television critic Maurice Wiggin had described as ‘a clinical touch, a whiff of the laboratory’.Footnote 77 By contrast, BBC-produced footage tended to be shot, as one journalist put it, on ‘sun-drenched safaris to faraway places’, giving a much airier, naturalistic aesthetic.Footnote 78 For television commentators, Granada productions could sometimes look dry and academic – ‘all in the can, assembled for projection’, as Wiggin averred – but in other contexts they could inspire praise for ‘precise photographic methods’ (Zuckerman on Van Hooff).

Van Hooff's film and paper also impressed Hall. He lauded the promising Dutchman in a letter to Zuckerman after the symposium and would cite the ‘interesting preliminary account of his [Van Hooff's] … general description and classification of facial expressive movements … in zoo monkeys and apes’ in a 1963 chapter surveying recent work on primate behaviour.Footnote 79 A wider measure of Van Hooff's academic contribution with this Granada-aided research was its status as a routine citation in the expanding specialism of primate facial expressions and the broader ethological and psychological literature.Footnote 80 While scientists from a variety of disciplines invoked Van Hooff for different reasons, his 1962 paper was usually referenced as the most comprehensive, if still preliminary, description and categorization of primate facial expressions.

Soon after the symposium, Van Hooff returned to the Netherlands, where his supervisor Sven Dijkgraaf provided him a teaching post and the opportunity to develop his facial-expressions research and work towards a PhD.Footnote 81 Television and film continued to play an important role in his research and communication activities. In September 1964, he began with his brother Antoon co-hosting Zoo Zoo, a top-rated monthly television programme modelled on Zoo Time, which gave him more opportunities to gather film. He also used the footage of ‘Animal expressions’ to create a visual argument demonstrating the function of facial expressions in dyadic interactions for a chapter in Primate Ethology, a volume edited by Morris and published in 1967.Footnote 82

Film stills in print

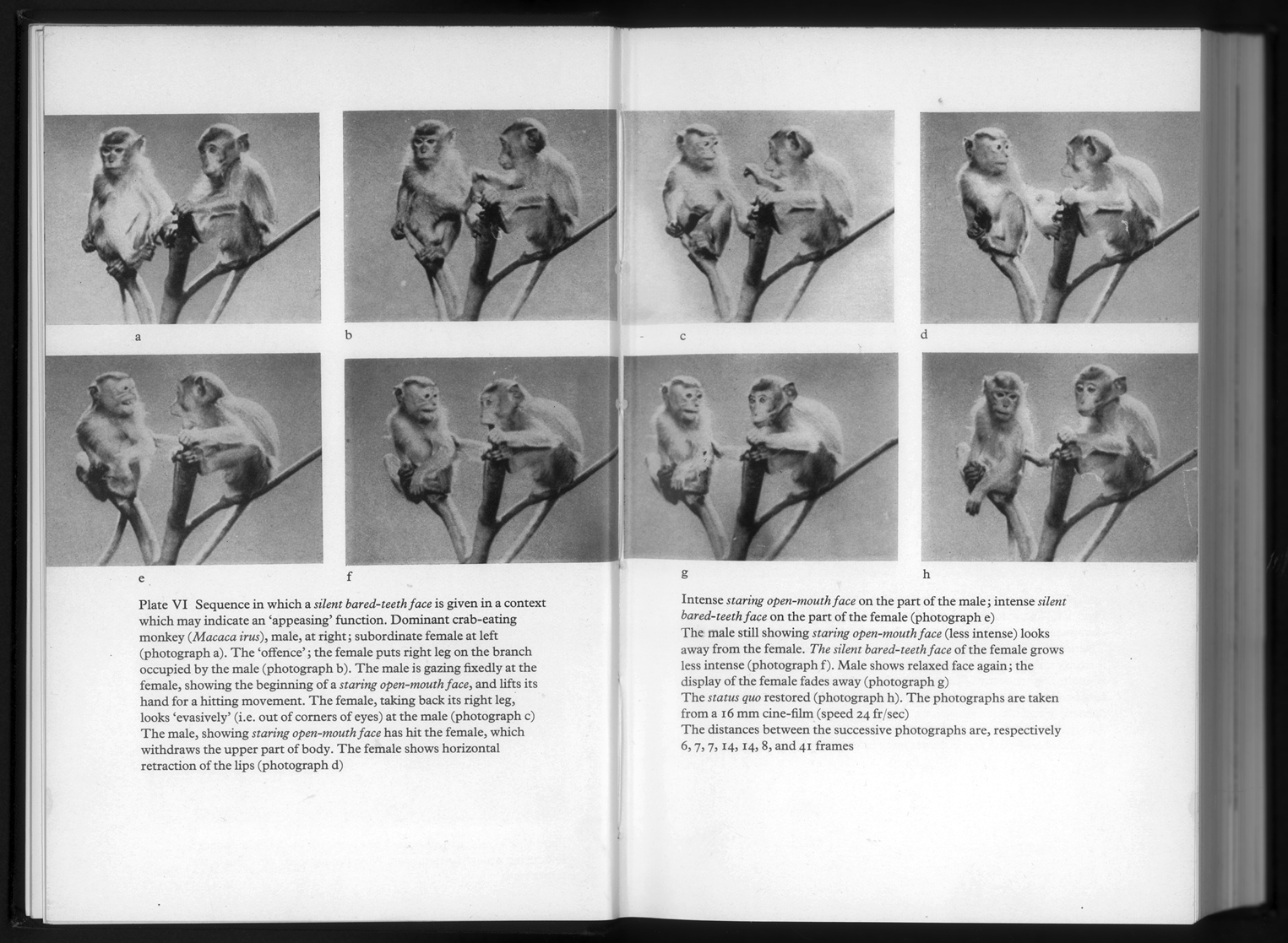

Using the footage from his collaboration with Granada, Van Hooff selected film stills and arranged them sequentially, producing a visual argument for his theory that an expression he called the ‘silent bared-teeth face’ had an ‘appeasement’ function. Recall the frontal two-shot of juvenile crab-eating monkeys. Cutting at irregular time intervals, Van Hooff segmented this sequence of around ten seconds into a series of eight stills on a double-page spread (Figure 6). He picked as his starting frame an ‘offence’, in the form of the subordinate female infringing upon the territory of the dominant male, which triggered the subsequent interaction.Footnote 83 The climax occurs in frames d to f. They show the male grabbing the female's arm while a ‘staring open-mouth’ face develops. The female begins responding to this aggression in frame d with ‘horizontal retraction of the lips’ which becomes the full-intensity ‘silent bared-teeth face’ shown in e. By g, both monkeys show ‘relaxed’ faces and the ‘status quo [is] restored’, insinuating that the female's display caused the male to cease his aggression. Rendering the stills in this way was a visual technique for elucidating the social functions of primate signals.

Figure 6. Double-page spread with frame-by-frame analysis of eight stills from ‘Animal expressions’ printed in Primate Ethology, London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1967, Plate VI. Reproduced with permission of the Licensor through PLSclear.

Primate Ethology received mixed academic reviews. While some criticized the volume's images as ‘in general … not adequate’, others praised its ‘excellent illustrations and commendably accurate documentation’. Jane Goodall's chapter, in particular, was applauded for its high-quality National Geographic photographs of wild chimpanzees.Footnote 84 Critical reviewers did not specify offending images, or the reasons for their objections. But Van Hooff's other frame-by-frame sequence of captive chimpanzees, shot for an episode of Zoo Zoo, could have provoked some of the negative response: a wire-mesh cage criss-crosses the already unfocused film stills in which expressions are barely discernible, a far cry from the slick glass-fronted studio shots of the Granada unit.

In a more positive review, anthropologist John Lawrence Angel pointed readers to the fruitful comparisons they could make between Van Hooff's images and the verbal descriptions of children's facial expressions in a later chapter by Nicholas Blurton Jones.Footnote 85 Angel's comments show how words and images reinforced one another to support Van Hooff's claim to have identified homologues of human smiling and laughter in the ‘silent bared-teeth face’ and the ‘relaxed open-mouth face’ respectively. While none of the reviewers explicitly acknowledged Van Hooff's frame-by-frame analysis – an early use of this method in primate research – it galvanized students in the late 1960s and the 1970s, notably Berkeley PhD student Suzanne Chevalier-Skolnikoff, to take up his filmic techniques.Footnote 86 Chevalier-Skolnikoff, however, lacked the resources that the Granada unit had given Van Hooff at a similarly junior stage. She was forced to record the interactions of her stump-tailed macaques through gaps in a wire-mesh enclosure with a lightweight, coarsely grained Super 8 camera, and to carefully conserve expensive film.Footnote 87 In publications, she could erase extraneous detail and disguise graininess by having drawings made, but the lack of purpose-built studios imposed low production values, as in Van Hooff's Zoo Zoo stills.Footnote 88 The Granada unit was a rare boon to primate ethologists.

Conclusion

Adapting the approach Tinbergen had developed with his students in their gull research, Van Hooff made an ambitious preliminary description and classification of primate facial expressions. Like a growing number of mammalian ethologists in the 1950s and 1960s, he made the moving image central to his practice, a shift facilitated by proliferating links between zoologists and broadcasters. The Granada unit specialized in this ‘entertainment–zoological complex’, catering simultaneously to ethologists and the public-service-oriented commercial television agenda of Granada in the age of Pilkington. The company found in Van Hooff's work a visually arresting topic and adapted it to a television grammar of framing human faces. The result was an informative, scientifically authorized and at times amusing addition to its schedule. Shot through with the studio- and zoo-based aesthetic of much of the Granada unit's film work, ‘Animal expressions’ showed primate faces and interactions in tightly framed sequences against monotone backgrounds to focus viewers’ attention and exclude distractions. This contrasted with the on-location filming that predominated in BBC natural history programmes and ultimately, through National Geographic-sponsored research, produced modern primatology's most abiding images.

Based for some fourteen months in London Zoo and the Granada unit, Van Hooff gained much that his counterparts at academic institutions lacked. He received early national and international exposure, including television interviews in which he began developing camera-friendly routines of exposition. In Van Hooff's hands, footage from ‘Animal expressions’ was a multivalent research and communication resource. With it, he put himself and his topic on the radar of leading primate researchers at the 1962 ZSL symposium. Through intermedial translations he cut sequences into the series of stills printed in Primate Ethology, an early example of this representational technique by a primatologist. In these ways, footage was made to serve a new specialism in behaviour research as well as a commercial television company as it negotiated a turbulent period of scrutiny and criticism. Ethologists and commercial television professionals were mutual beneficiaries of this filmmaking project.

Through its alliance with London Zoo ethology, the Granada unit provided ITV with captivating programmes such as ‘Animal expressions’ which exemplified pioneering ethological research and distinguished the new channel's natural history output from that of its BBC rival. Too often dismissed as a purveyor of facile entertainment, ITV was, thanks to the Granada unit, for a period the leading innovator in the content and format of natural history television. Further work on the science of commercial television in this formative period of television history will help to balance a BBC-centric historiography.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Nick Hopwood, Helen Curry and the editor and two anonymous referees of the BJHS for their wealth of insightful comments and suggestions on drafts. In addition, I thank those who gave feedback at the BSHS Online Conference 2021. For generously sharing their memories and photographs, I thank Jan van Hooff and Desmond Morris. For invaluable remote archival assistance, I am indebted to Sarah Broadhurst (Zoological Society of London) and Robin Bray (ITV). I am grateful to Ian Bolton and Adrian Newman (Anatomy Visual Media Group) for preparing figures. This research was generously supported by the Arts and Humanities Research Council (grant number AH/R012709/1), a BSHS research grant, and my department.