Alonzo Jacob Ransier approached the podium at the Southern States Convention of Colored Men assembled in Columbia, South Carolina, on October 18, 1871. He had just been elected president of the gathering that included delegates from Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, Maryland, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, and Washington, DC. Ransier was a native South Carolinian born to free Black parents in 1834; he represented Charleston at the South Carolina State Constitutional Convention of 1868, then served in the state House of Representatives, and was now the state's first Black lieutenant governor.Footnote 1 “Upon your action, gentlemen, depends, in a great part, the future of the colored man, at least in the Southern States.”Footnote 2 The delegates later composed an “Address to the People of the United States” that read in part, “the instantaneous embodiment of four millions of citizens who had for years looked upon the Government as not only denying them citizenship, but as preventing them from acquiring that capacity under any other national existence, was, it must be admitted, a startling political fact.”Footnote 3 Temporal themes were not just rhetorical flourishes—Ransier and his colleagues deployed time as a tool by which to advance their rights.

The Southern States Convention debates provide abundant evidence that Black southerners relied on imagery and narratives of the past, present, and future in their advocacy efforts. The Committee on Education wrote, “the question of education is, to the people of color, one of a most vital importance … for nearly two centuries and a half, nineteen-twentieths of four millions of human minds—and minds susceptible of the highest cultivation, evidenced in numerous cases—have been shut out from the invigorating and regenerating influences of education.”Footnote 4 And the Committee on Labor noted, “the condition of the colored population of this country is such that under the new order of things it becomes them to assume grave and important duties unknown to them in the past.”Footnote 5 J. F. Quarles of Georgia provided to the convention an account of “The Social Problems of the South”:

And now we ask the Southern people, in all candor, if we have not borne this species of oppression long enough? We are weary of being consumed by this moloch, caste; we are weary of being hunted down by the ghosts of the defunct system of slavery; we are weary of being reminded of servitude more galling than Egyptian bondage; we are weary of being treated as outcasts and strangers in the land of our nativity, and the home of our fathers; and we ask, as it is our right, that these odious discriminations shall cease. Too long, already, have they been allowed to bear sway in this country. And surely now the time has come when their influence should be destroyed; the time has come when their power ought to be broken; the time has come when they should perish from the land.Footnote 6

The Colored Conventions Movement served as a public political forum where African Americans could speak to each other, state governments, the federal government, and the nation.Footnote 7 Delegates adopted the language of temporality in pursuit of justice and equality. They used the past to correct the historical record, the present to convey the urgency of the new post-emancipation era, and the future to advocate on behalf of labor rights and public education.

During the nineteenth century, African Americans gathered in many conventions to condemn slavery, advocate for their rights, demand equality, and debate paths forward. Frederick Douglass, Henry Highland Garnet, John Mercer Langston, Charles Langston, and Henry McNeal Turner were regular participants, as were hundreds of other Black leaders and citizens from across the country. The meetings were largely dominated by men, though recent scholarship has found multiple paths of influence by Black women.Footnote 8 These conventions are neglected resources that offer an indispensable view into African American political organizing and public debate over a range of policy and constitutional issues. The debate was taking place in other forums as well, but these gatherings were especially important. According to Eddie Glaude Jr., the early antebellum conventions “represent the first national forum for civic activity among African Americans.”Footnote 9 The same is true for those held during and after Reconstruction in the South, where public political discourse had previously been reserved for whites.

The Colored Conventions Project at the University of Delaware has digitized and compiled transcripts from the movement.Footnote 10 The founding director of the project, P. Gabrielle Foreman, argues that convention records offer an “articulation of Black subjectivity and the assertion of Black worth, ambition, and belonging in North America with which scholars have yet to fully grapple.”Footnote 11 She also notes that historical scholarship so often focuses on individual narratives that it can “obscure foundational commitments to Black collective authorship and address.”Footnote 12 These were “spaces for concrete planning, coordination, and advocacy for equal justice and freedom through collective efforts.”Footnote 13 As such, careful consideration of the debates exposes additional evidence of the profound influence by Black activists on American political thought and development.

The American South has a fraught relationship with time. In fact, it is the purposeful construction and manipulation of time, history, and public memory that has defined Southern politics. White supremacists shaped perceptions of the past through stories of an “Old South,” a “Lost Cause,” and many promises of a “New South” in their effort to secure power and the racial hierarchy. State governments used time to control the distribution of rights through grandfather clauses, curfews, jail time, convict leasing, vagrancy laws, labor regulations, and other legal mechanisms. Landholders abused African Americans through a sharecropping system that relied on a variety of temporal constraints, including annual contracts (sanctioned and often required by the state) and credit arrangements with exorbitant interest rates on farming equipment, seed, and fertilizer. The result was a post-emancipation system of agriculture that more closely resembled slavery than free market capitalism. All the while, public space and public history valorized whites and ignored or vilified Blacks.

Scholarship on political development in the South should not always be divided by race, but experiences with time varied across the color line. Desmond King and Rogers Smith argue that “American politics has historically been constituted in part by two evolving but linked ‘racial institutional orders’: a set of ‘white supremacist’ orders and a competing set of ‘transformative egalitarian’ orders.”Footnote 14 In his groundbreaking work on Reconstruction, Richard Valelly describes a “parallel politics” in which “blacks used open-air settings, public spaces, and, in some cities, churches for broadly political purposes, even as presidential reconstruction denied freedmen access to official spaces of capitols and county courthouses.”Footnote 15 And P. Gabrielle Foreman uses the term “parallel politics” to describe the Colored Conventions Movement itself.Footnote 16 Unfortunately, the vast majority of scholarly energy has been spent on the white South, wherein African Americans are often portrayed as pawns in the Southern political drama instead of people with agency.

Nell Painter writes, “for too long we have normalized whiteness, as though to be white were to be natural.… ‘Southerner’ used to mean only ‘white southerner,’ as though black southerners were not part of the South.”Footnote 17 The course of American politics, however, was continuously shaped by the actions of Black southerners, who had their own relationship with temporality—they did not gaze back longingly on a lost past, and their vision for a New South required a fracture in the path of development.Footnote 18 This relationship operated in a segregated but connected realm. The enslaved were trapped in an archaic, evil institution that prohibited any social advancement. Emancipation and the transformation from property to citizen was a critical juncture, a new founding moment in Black southern time. African Americans then had to counter white supremacist mythology about the past and resist laws and practices that were devised to control their time. Segregation itself is steeped in temporality—the basic structure of the Jim Crow South required that Blacks wait for whites to receive any public goods or rights before they could access the leftovers.

During the Civil Rights Movement, activists used the language of temporality to convey urgency in the fight for equality. Martin Luther King Jr. produced works titled “Why We Can't Wait” and “Negroes Are Not Moving Too Fast.”Footnote 19 In his most famous address, he invokes the broken promises of the past before warning,

Now is the time to make real the promises of democracy. Now is the time to rise from the dark and desolate valley of segregation to the sunlit path of racial justice. Now is the time to lift our nation from the quick sands of racial injustice to the solid rock of brotherhood. Now is the time to make justice a reality for all of God's children. It would be fatal for the nation to overlook the urgency of the moment.Footnote 20

King then builds to a crescendo by outlining his dream of a more just future. Bobby Seale closed his account of the Black Panther Party, with a call to African Americans, “We know that as a people, we must seize our time.”Footnote 21 After her acquittal, Angela Davis told the nation, “it is justice that we seek, and many of us can already envision a world unblemished by poverty and alienation, one where the prison would be but a vague memory, a relic of the past. But we also have immediate demands for justice right now, for fairness, and for room to think and live and act.”Footnote 22 These twentieth-century Black activists were standing upon a rhetorical foundation built by those who preceded them.

After defeat in the Civil War, white southerners sought to obscure a heinous past while maintaining the racial hierarchy that past had produced. Black southerners, on the other hand, began a whole new historical experience that required constant advocacy and sacrifice to secure the rights they had been promised during and after Reconstruction. They petitioned the Union Army, the federal government, state governments, and the greater public across this period in many different ways. I am investigating how they used time as a rhetorical tool to fight oppression and demand equal treatment and justice. The extant transcripts from the Colored Conventions Movement contain an important record of these efforts. Participants used public interpretations of the past, present, and future and the language of temporality to counter the work of white supremacists. Their efforts demonstrate that citizens and social movements, like governments, can wield time as a tool to shape politics.

1. Time as a Political Tool

Scholars of American political development (APD) often claim that “history matters” and we ought to take time seriously. According to Paul Pierson, careful consideration of timing and sequence offers a better understanding of political outcomes.Footnote 23 Attention to sequence speaks to an emphasis on “path dependence,” a concept that describes the growing costs of changing course over time, especially in economic or institutional development.Footnote 24 Other scholars use “multiple orders” to describe numerous political components progressing at different temporal speeds and logics.Footnote 25 And some are interested in progression after “critical junctures” (war, economic calamity, etc.).Footnote 26 Karen Orren and Stephen Skowronek attempt to synthesize the goals of subfield and tap its “fuller significance”—meaning “what it is APD might teach us about how past and present politics are connected, by what bridges or processes; about how time comes to exert an independent influence on political change, apart from the notion that time ‘passes.’”Footnote 27 Some work in APD examines the influence of time on developmental pathways, but this approach misses how essential temporality is to understanding racial dynamics in the nation and the fact that the state and citizens can wield time as a political tool through laws, policing, economic arrangements, and public rhetoric.

In a recent book, The Political Value of Time, political theorist Elizabeth Cohen argues that “scientifically measured durational time is a highly significant and underexplored political good,” “time is a tool in the arsenal of a state,” and governments exert control over the lives of citizens through a variety of temporal mechanisms—elections, political terms, censuses, taxes, prison sentences, naturalization procedures, welfare benefit requirements, military service, and probationary/waiting periods.Footnote 28 Charles Maier also recognizes a politics of time built into governance, while Stephen Hanson and Christopher Clark connect the manipulation of time to communist and fascist regimes.Footnote 29 Sociologists Donatella della Porta, Massimiliano Andretta, Tiago Fernandes, Eduardo Romanos, and Markos Vogiatzoglou argue that transitions to democracy operate as critical junctures during which social movements can exploit legacies and memories of the past to build solidarity and spur institutional change (the Black Southern conventions considered here also gathered during democratic transition—one that ultimately failed).Footnote 30 This scholarship shows that time can be used by those with power to undermine democracy and within individual movements. In this article, I demonstrate that subjugated groups can also use time to challenge those with power and the state.

Another conceptual facet that Cohen's work helps elucidate is the notion that emancipation marked not just a critical juncture but a new founding moment. She argues that “time and territory are both implicated in the creation of political boundaries,” and “temporal boundaries separate in from out, enfranchised from disenfranchised, and rights-bearing from rightless.”Footnote 31 Cohen refers to “zero-option rules,” which establish a temporal line, “a specific date upon which a form of legal sovereignty commences.”Footnote 32 The Emancipation Proclamation and then the Thirteenth Amendment shifted one of these central legal boundaries, and the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments moved that boundary yet again. For many convention participants, the abolition of slavery was a revolution akin to the break with England, a seconding founding. Thus, they were not just wielding temporal rhetoric, they were doing so at a rare point in history where the zero-option rules were operating in American politics.

Many of the temporal themes I locate in the Colored Conventions Movement appear in W. E. B. Du Bois's Black Reconstruction. The entire book provides a template for considering the past, present, and future of the era.Footnote 33 The larger goal of Black Reconstruction is to correct a racist historiography and corrupted public memory. Du Bois laments that in the service of martyring the South, we have “completely misstated and obliterated the history of the Negro in America and his relation to its work and government.”Footnote 34 The opening line of the book indicates that emancipation was not just a critical juncture but the critical juncture: “Easily the most dramatic episode in American history was the sudden move to free four million black slaves in an effort to stop a great civil war, to end forty years of bitter controversy, and to appease the moral sense of civilization.”Footnote 35 Du Bois argues that the labor regulations and vagrancy laws of the black codes "looked backward toward slavery.”Footnote 36 Moreover, “through establishing public schools and private colleges, and by organizing the Negro church, the Negro had acquired enough leadership and knowledge to thwart the worst designs of the new slave drivers.”Footnote 37 Scholar Charles Lemert believes that Black Reconstruction is primarily “about the perverse nature of historical time and its effects on the democratic ideal and the future of civilization.”Footnote 38

In The Souls of Black Folk, Du Bois writes of how the postwar period “swayed and blinded men,” and that

Amid it all, two figures stand to typify that day to the coming ages,— the one, a gray-haired gentleman, whose fathers had quit themselves like men, whose sons lay in nameless graves; who bowed to the evil of slavery because its abolition threatened untold ill to all; who stood at last, in the evening of life, a blighted, ruined form, with hate in his eyes;—and the other, a form hovering dark and mother-like, her awful face black with the mists of centuries, had aforetime quailed at that white master's command, had bent in love over the cradles of his sons and daughters, and closed in death the sunken eyes of his wife,—aye, too, had laid herself low to his lust, and borne a tawny man-child to the world, only to see her dark boy's limbs scattered to the winds by midnight marauders riding after “cursed Niggers.” These were the saddest sights of that woeful day; and no man clasped the hands of these two passing figures of the present-past; but, hating, they went to their long home, and, hating, their children's children live today.Footnote 39

He warns that the past is always present, restricting rights and democratic progress for subsequent generations of Black southerners. Gregory Laski argues that with this notion of the “present-past,” “Dubois reorders linear time—positioning the past after, rather than before, the present—and insists on intergenerational responsibility as a crucial democratic value alongside equality and liberty.”Footnote 40 In both works, separated by over three decades, Du Bois binds temporality to the failed democratization of the South.

I rely on Michael Hanchard's ideas about the racial dimensions of time and memory to further illustrate the benefits of a temporal framework. He argues, for instance, that African Americans must often work together to preserve their own version of public memory, “Black memory,” to counter white accounts and make claims “about the relationship between present inequalities and past injustices.”Footnote 41 And Hanchard defines “racial time” as “the inequalities of temporality that result from power relations between racially dominant and subordinate groups,” including “unequal temporal access to institutions, goods, services, resources, power, and knowledge, which both groups recognize.”Footnote 42 There are three conceptual facets of racial time: “waiting,” “time appropriation,” and “the ethico-political relationship between temporality and notions of human progress.”Footnote 43 Waiting refers to the stolen time that subordinate groups must endure to access goods, services, and even rights that are “delivered first to the dominant group.”Footnote 44 Time appropriation is marked by “efforts to eradicate the chasm of racial time” by social movements or other groups, and it “mostly occurs during periods of social upheaval and transformation.”Footnote 45 The final conceptualization is built on “the belief that the future should or must be an improvement on the present.”Footnote 46

There are other approaches to investigating the Colored Conventions Movement broadly and in the South after the war. Eddie Glaude Jr., for instance, argues that the first Black national conventions of the 1830s used the biblical story of Exodus in the struggle against slavery and for rights and recognition.Footnote 47 And “by appropriating Exodus, they articulated their own sense of peoplehood and secured for themselves a common history and destiny.”Footnote 48 Glaude emphasizes the secular nature of Exodus to highlight its “political value.”Footnote 49 After emancipation, Southern Black conventions saw the political value of time and used it to pursue many of the same goals for which their antebellum predecessors relied on the Exodus story—recounting the past, espousing Black nationalism, organizing to confront racial violence, countering claims by whites, and imagining a better future.Footnote 50 For Historian Selena Sanderfer, “the unwavering insistence on land acquisition and economic independence as a basic human right clearly distinguished Black southern nationalists.”Footnote 51 Her work highlights the importance of “space” for those who had been enslaved. It is time, however, that connects debates over property, labor, and education to the larger goals of the movement—justice, democracy, freedom, and equality. The following analysis reveals that the temporal rhetoric of citizens and social movements can operate as a political tool to counter the efforts of those in power, and it presents a new theoretical approach for studies of time and APD.

2. The Colored Conventions Movement and Temporal Agency

Organization of the Colored Conventions Movement during the antebellum era was almost completely limited to the North. Between 1830 and 1864 there are records of sixty-two conventions: thirteen national, two regional, and forty-seven state conventions.Footnote 52 The 1852 Maryland state convention was the only meeting in a slave state, and there were none in Washington, DC, until 1865. These were essential locations of activism and debate over issues that included abolitionism, education, temperance, religion, emigration, and African colonization.Footnote 53 The American Moral Reform Society was heavily involved in the early movement, and Black conventions can be connected to the rise of the Black newspaper, which, in turn, helped spur more conventions.Footnote 54 In his study of the Black state conventions of the 1840s, Derrick Spires claims that convention records should be considered “political documents central to an understanding of citizenship practices in the antebellum United States.”Footnote 55

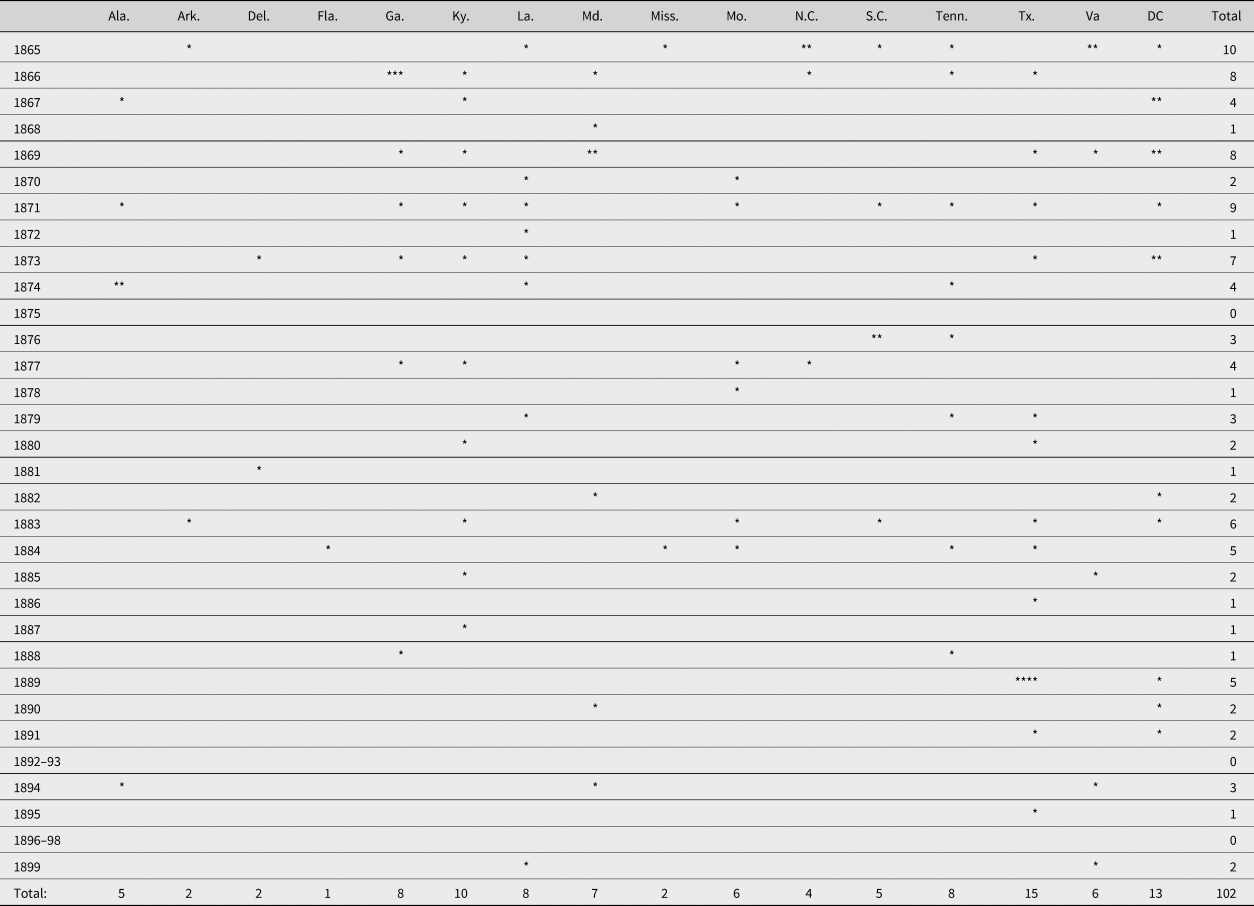

Table 1. Colored Conventions Movement, 1830–1900

After the Civil War, African Americans continued to gather in conventions for public debate and advocacy. Between 1865 and 1900, there are records of sixty-five conventions outside the South: seven national, two regional, fifty-six state (just three more than in the previous thirty-five years).Footnote 56 At first glance, the movement appears steady, but participation dramatically increased in the South, where the millions of new citizens, many of whom had previously been held in bondage, gathered to debate the path forward and speak publicly to the Black community, to the white community, and to state and federal government officials.Footnote 57 In their account of the postwar movement, Philip Foner and George Walker note that “defeat of the slaveholders’ rebellion did not eliminate the need for conventions. On the contrary, to make meaningful the Northern victory, organization and action by blacks themselves were essential.”Footnote 58 And it is these Southern conventions that have been most neglected by scholars.Footnote 59

For the purposes of this article, I define the South as those states where slavery was legal as of 1860: Alabama, Arkansas, Delaware, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maryland, Mississippi, Missouri, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, and Virginia. I also include Washington, DC, where slavery was legal until 1862. This allows me to focus on the efforts of emancipated Black southerners contending with new historical circumstances. There are records of 102 conventions (twenty-one national, one regional, seventy-four state, three county, and three city) in the South between 1865 and 1900.Footnote 60 As with state constitutional conventions during the era, most of the activity was in the South.Footnote 61 Texas held fifteen, followed by Washington, DC, with thirteen; Kentucky with ten; Louisiana, Georgia, and Tennessee with eight; Maryland with seven; Virginia and Missouri with six; South Carolina and Alabama with five; North Carolina with four; Arkansas, Delaware, and Mississippi with two; and Florida with one.Footnote 62 Within those, there were two national and six state conventions on labor, four state conventions on education, three state teacher's conventions, seven national press conventions, and one state farmers convention.Footnote 63

Table 2. Colored Conventions Movement in the South, 1865–1900

The convention movement unfolded in a variety of ways across the South, but these gatherings were connected by similar goals and themes, including education, equality, voting rights, officeholding, labor rights, and emigration.Footnote 64 Black leaders in Tennessee began organizing in the summer of 1864, issuing a call that “every colored man, woman and child come spend one day in the cause of human Freedom and human equality … for the future freedom of our race.”Footnote 65 In Alabama, Black citizens gathered to advocate for rights after the war, like elsewhere in the region, but additional conventions were required in the 1870s to respond to the white supremacist “redemption” of the state government and ongoing violence—even debating an exodus from the region.Footnote 66

Those who participated in the Colored Conventions Movement in the South from 1865 to the turn of the twentieth century deployed the temporal rhetoric of the past, present, and future in their pursuit of equality and racial justice by: (1) publicly recounting African American history and national contributions to counter white narratives, (2) arguing that emancipation was a new founding moment and the present a time of ongoing crisis, and (3) demanding labor rights and public education to secure the future of the race. First, they sought to correct the historical narrative that was under active revision by forces of white supremacy. This was accomplished by publicly acknowledging the principles of freedom and equality contained in the Declaration of Independence and Constitution, the military service of African Americans in every national conflict, the essential part Blacks played in the economic development of the country, and the brutality and oppression that pervaded the institution of slavery. Second, delegates argued after the critical juncture of emancipation that the present was a time of crisis (ongoing from the beginning of Reconstruction through the rise of Jim Crow) that required political action. Third, they insisted that labor rights and public education were essential to secure the future of the race. These temporal mechanisms track those used by white supremacists: Recounting the evils of slavery undermines the notion of the Old South; emphasis on the military service of African Americans can be balanced against Stonewall Jackson, Robert E. Lee, and other rebel soldiers of the Lost Cause; and treating the present as a moment of crisis where decisions would dictate the path of public education, labor rights, and ultimately political equality offered a Black vision of the New South.

2.1 Correcting the Past

Delegates highlighted the contributions that enslaved and free African Americans made to the nation, usually under immense suffering. These public narratives represented an attempt to correct the historical record, just as the white South and their political and academic allies were rewriting the causes of the war and the brutalities of slavery through images of the Old South and the Lost Cause.Footnote 67 Historian William Dunning, political scientist John Burgess, and many others perpetuated the image of happy slaves and benevolent masters, blamed the North for the damage of the war and the failures of Reconstruction, and demonized the efforts of Black southerners to secure their rights and change the politics of the region.Footnote 68 Du Bois dissents in Black Reconstruction and notes that “no serious or unbiased student can be deceived by the fairy tale of a beautiful Southern slave civilization.”Footnote 69 Unfortunately, it was the Dunning School that had a larger influence on the academic approach to Southern political history, especially the racist narratives regarding Reconstruction.

Du Bois implies that segregated society leads to a segregated memory of the past, and Michael Hanchard notes that “Black memory … is often at odds with state memory,” which pushes nationalism through public symbols, rituals, and rhetoric.Footnote 70 P. J. Brendese defines “segregated memory” as “the distinctly racialized encounters with haunting pasts that separate citizens of a polity.”Footnote 71 But there is a danger to democracy that flows from the differing accounts of the past by the white and Black South. Brendese cites the work of Orlando Patterson for the consequences of white supremacists controlling history: “Slaves differed from other human beings in that they were not allowed to freely integrate the experience of their ancestors into their lives, to inform their understanding of social reality with the inherited meanings of their natural forebears, or to anchor the living present in any conscious community of memory.”Footnote 72 There is also a rich historiography that considers public memory, and much of this scholarship is devoted to the Southern experience.Footnote 73 Part of the mission of the conventions studied here was to influence how society, Black and white, remembered the institution of slavery and the national contributions of African Americans.

Participants in the Colored Conventions Movement corrected the historical record as it was being distorted, highlighting their dedication to founding principles. An 1865 Virginia convention approved a set of resolutions that began, “we and our fathers have from sixteen hundred and twenty until now, both by our sweat and our blood, helped to make the country what she is in wealth, in power, and in greatness”; they then claimed that the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution guaranteed “a perfect equality before the law.”Footnote 74 In Washington, DC, William Howard Day provided a history of slavery to the Colored People's Education Monument Association but praised the founding ideals, “then that there was sent forth upon the wings of the wind the Declaration of Independence, read to-day; one of the greatest documents the world has ever seen—great, with reference to the occasion which brought it forth—great, with respect to humanity, in all coming time.”Footnote 75 Day's entire address is steeped in temporal themes.

Convention notes indicate that Black southerners saw themselves as Americans and used connections with the past to advocate inclusion and equal rights. In early 1866, delegates in Georgia crafted an address to the state legislature that read in part,

Suffering from consequent degradation of two hundred and forty-six years of enslavement, it is not to be expected that we are thoroughly qualified to take our position beside those who for ages have been rocked in the cradle of education. But we are willing to bury the past, and forget the ills of slavery, and assume the attitude of a free people.… The dust of our fathers mingle with yours in the same grave yards.… This is your country, but it is ours too; you were born here, so were we; your fathers fought for it, but our fathers fed them.Footnote 76

That same year, in Kentucky a set of resolutions asserted that “we are part and parcel of the Great American body politic; … we are intensely American, allied to the free institutions of our country by the sacrifices, the deaths and the slumbering ashes of our sons, our brothers and our fathers.”Footnote 77 And in 1871, the Colored Citizens of Tennessee wrote to Congress, “As in the past, we in the future, pledge to you all of your efforts, to stand firm to our country, unfetter the chains of the oppressed and break the yoke of the captor.”Footnote 78 They presented a public rebuke of the stories of contented slaves and kind masters, while expressions of national pride and loyalty buttressed claims of citizenship.

The debates also offered a proper recounting of the fundamental contributions of African Americans to the development of the nation and of the South in particular. The National Equal Rights League of Colored Men issued a statement to Congress, “the bones of our fathers and of our fathers’ fathers lie here. Our sweat has moistened this soil; our hands have felled your Southern forests, and made the wealth of your cotton, rice, and sugar plantations.… We propose, therefore, to remain here and cast ourselves upon your generosity and justice.”Footnote 79 In Lexington, delegates wrote to the General Assembly that “much of the property now constituting the aggregate wealth of Kentucky has been acquired or improved, in whole or in part, by our labor.”Footnote 80 Colonel Robert Harlan, who had been born a slave, warned against emigration at a national convention in 1879: “The southern country is ours. Our ancestors settled it, and from the wilderness formed the cultivated plantation, and they and we have cleared, improved, and beautified the land.”Footnote 81 J. C. Corbin of Arkansas agreed that the labor of African Americans “is the basis of the wealth of the South.”Footnote 82 And the “Address to the Colored People of Texas” reminded Black citizens that “our labor as slaves made the south one of the wealthiest agricultural countries of the world.”Footnote 83

Black southerners were also aware of the ongoing attempts by white southerners to rewrite history. At the National Convention of the Colored Men of America in 1869 a portion of a report from the Judiciary Committee read,

I would call your attention to the title of a book recently written by Alexander Stephens. Holding to the old doctrine on which secession was built he gives his book the title, “War between the States,” thinking thereby to blink out of sight the historical truth that the war was not between the States as such, but one in which the supreme and sovereign Government subdued the rebellious subject States. And before I leave this point, permit me to say that if a man of his ability, of his antecedents, would seek at this late day to impress such a pernicious doctrine on the public mind, it exhibits in the clearest light the importance of settling this question of state power beyond the possibility of a doubt.Footnote 84

Then in 1879, the former African American Governor of Louisiana, Pinckney B. S. Pinchback, told delegates in Tennessee, “the love and respect of the white race for their prominent men … is illustrated in the South by the reverence they have for the memory of Robert E. Lee. In its great centers monument piles are erected to perpetuate his memory.”Footnote 85 The Colored Conventions Movement was an opportunity for African Americans to publicly honor and revere their own efforts in building the nation and to provide a counternarrative.

Many Southern conventions focused on the history of African American military service. In June of 1865, the address drafted in Virginia included the following:

Why, the first blood shed in the Revolutionary war was that of a colored man, Crispus Attucks, while in every engraving of Washington's famous passage of the Delaware, is to be seen, as a prominent feature, the wooly head and dusky face of a colored soldier, Prince Whipple; and let the history of those days tell of the numerous but abortive efforts made by a vindictive enemy to incite insurrection among the colored people of the country, and how faithfully they adhered to that country's cause. Who has forgotten Andrew Jackson's famous appeal to the colored “citizens” of Louisiana, and their enthusiastic response, in defence of liberty, for others, which was denied themselves?Footnote 86

In September 1865, in Newbern, North Carolina, Abraham Galloway, who was enslaved before escaping and working as a Union spy, military recruiter, and Republican politician, argued “if the negro knows how to use the cartridge-box, he knows how to use the ballot-box.”Footnote 87 Two months later in Arkansas, William Henry Grey, an African American politician and Republican Party organizer, recounted the history of Black military service and said, “Our future is sure—God has marked it out with his own finger; here we have lived, suffered, fought, bled, and many have died. We will not leave the graves of our fathers, but here we will rear our children; here we will educate them to a higher destiny; here, where we have been degraded, will we be exalted.”Footnote 88 These leaders were not just asking for rights of African Americans as a concession, they used history to demonstrate that the rights had been earned.

At the National Equal Rights League of Colored Men Convention in 1867, delegates argued that service in the Civil War entitled them to “share of the fruits of victory—freedom, manhood, all the rights and privileges of citizenship.”Footnote 89 The address they composed read, “Need we remind you that amid the darkest hours of the late war we came promptly at your call.… That conflict is now past, and the records of your history testify that we fought and suffered nobly, and that on our part we have fulfilled faithfully those conditions.”Footnote 90 Attendees also referenced service in other conflicts, “When you fought for national independence colored soldiers were by your side; colored regiments swelled your brigades, and shared with you the sufferings, the hardships, and the conflicts unto blood by which you became an independent nation.”Footnote 91 And in “the British war of 1812, colored regiments fought and bled. You will remember the glowing testimony which their heroism drew from the lips and the pen of Andrew Jackson after the great and decisive battle of New Orleans.”Footnote 92 Reference to Andrew Jackson's approval of Black soldiers at the Battle of New Orleans is recurrent in the notes of several conventions.Footnote 93

The public accounting of Black military service appears frequently. Delegates in Baltimore argued voting rights were “due to us from our citizenship.… We have helped to fight the country's battles; we have stood shoulder to shoulder with white men, in every contest from 1776 to 1865.… Will the nation cast off us who have been its defenders?”Footnote 94 As in the twentieth century, African Americans used their sacrifices on behalf of the nation to demand equal treatment under the law.Footnote 95 And they did so through a public recounting of the past that contradicted the dominant white narratives and the public reverence shown for the leaders and soldiers of the Confederacy.

2.2 The Urgency of the Present

There have been many pivotal dates in the path of American political development. Giovanni Capoccia explains that in historical institutionalism the study of “critical junctures” is “the analysis of the politics of institutional change during a relatively brief phase which is characterized by the availability of different courses of action capable of affecting future institutional development in the longer term.”Footnote 96 Collier and Collier point to “a period of significant change that occurs in distinct ways in different countries (or in other units of analysis) and is hypothesized to produce distinct legacies.”Footnote 97 Paul Pierson argues that “contingency” is one of the four features of path dependence. Contingency means that “relatively small events, if occurring at the right moment, can have large and enduring consequences.”Footnote 98 Sociologist George Wallis uses the term “chronopolitics” “to emphasize the relationship between the political behavior of individuals and groups and their time-perspectives.”Footnote 99 Wallis argues that “the view of the present as a period of crucial decisions leads to the politics of crisis,” and “the perception of the present as a ‘time of transition’ in this sense suggests that those who have control at this critical time will mold that tomorrow.”Footnote 100 And for Hanchard, racial time can be divided into two phases—the pre-emancipation and post-emancipation periods.Footnote 101

Delegates often spoke of the historical moment and referred to the fact that they were operating at a crucial point in time (which was ongoing throughout the period as crisis after crisis emerged), separate from the past, where their decisions and actions could have far-reaching consequences for the future. P. B. S. Pinchback described emancipation to the Louisiana State Colored Men's Convention in 1871 as “the ruptured political and social relations of 4,000,000 people placed for solution before the nation a problem hitherto unsolved.”Footnote 102 The use of temporal themes in a public forum for the once voiceless members of Southern society allowed these men and women to demand immediate political action.

Emancipation was both a critical juncture and a new founding moment. Frederick Douglass viewed the Civil War as “apocalyptic,” according to historian David Blight.Footnote 103 In February 1863, Douglass delivered an address on the implications of the Emancipation Proclamation at the Cooper Institute, “Assuming our Government and people will sustain the President and the Proclamation, we can scarcely conceive of a more complete revolution in the position of a nation.… Henceforth that day shall take rank with the Fourth of July. (Applause.) Henceforth it becomes the date of a new and glorious era in the history of American liberty.”Footnote 104 The conventions that gathered in the South after the war also saw the connection between 1776 and 1863—Black southerners were starting anew as citizens of the nation; this was the beginning of a new era, a founding moment for those excluded during the first American revolution. And, as Elizabeth Cohen shows in her work on time, boundaries like emancipation result in a new legal sovereignty for some citizens, in this case African Americans.Footnote 105

In an editorial from a prominent Black newspaper, the New Orleans Tribune, the authors described the first state convention to meet in the postwar South as having “inaugurated a new era … a great spectacle, and one which will be remembered for generations to come,” but warned, “this is the time, and if you let the opportunity slide and pass away, you will be forever a downtrodden people.”Footnote 106 Observers of the conventions, as well as the delegates, recognized the import of the moment. William Howard Day spoke in Washington, DC: “We meet under new and ominous circumstances to-day. We come to the National Capital our Capital with new hopes, new prospects, new joys, in view of the future and past of the people.”Footnote 107 James Walker Hood, once a Pennsylvania abolitionist and now a transplanted southerner, told delegates, “There had never been before and there would probably never be again so important an assemblage of the colored people of North Carolina as the present in its influence upon the destinies of the people for all time to come.”Footnote 108 And in a memorial to the State Legislature and United States Congress, the Convention of the Colored Citizens of the State of Arkansas wrote, “We believe the time has come when wisdom again asserts her sway in the councils of the nation,” followed by a poem:

Kentucky delegates drafted resolutions that exalted freedom and hailed “the day of our Emancipation, as the brightest in the calendar of the nineteenth century.”Footnote 110

At an 1865 Virginia convention, Henry Highland Garnet composed an address with Fields Cook, a Baptist minister who was once enslaved, that connects the recounting of African American history to the urgency of the moment. They begin, “As a branch of the human family we have for ages been deeply and cruelly wronged, and by a people with whom might constituted right.”Footnote 111 Then: “We have been compelled, under pain of death, to submit to injuries deeper and darker than earth ever witnessed in the case of any other people.… When the nation in her hour of trial called her sable sons to arms, we gladly went and fought her battles.… We fought and conquered but have been denied the benefits of victory.”Footnote 112 They rejected the idea of emigration because “as natives of American soil we claim the right to remain upon it … for here we were born, and for this country our fathers and brothers have fought, and we hope to remain here in the full enjoyment of enfranchised manhood and its dignities.”Footnote 113 The address closed, “That emerging as we are from the long night of gloom and sorrow, we are entitled to, and claim the sympathy and aid of the entire Christian world. We invoke the considerate aid of mankind in this crisis of our history, and in this hour of our trial.”Footnote 114 The title chosen by the authors was “Our Wrongs and Rights,” and the entire structure was temporal, moving from the wrongs of the past to the significance of the present to the rights necessary for the future.

After the ratification of the Fourteenth Amendment in 1868, Black southerners saw a new urgency in the political moment. A national convention in January 1869 distributed an “Address to the Colored Citizens of the United States,” which noted,

we speak to you under far different circumstances from those in which you have been addressed by your assembled representatives at other periods of our history … we have reason to rejoice in the fact that the past has had its triumphs for us; but our condition in the present, together with the duties and responsibilities which it enforces upon us, demands our attention.Footnote 115

Bishop Daniel Payne, born in South Carolina and a prominent leader of the African Methodist Episcopal Church, sent a letter that was read to delegates: “Perhaps at no period of our history, was it was it so needful that the voice of Colored Americans be heard addressing the State and National Legislatures, and counselling one another as the present time.”Footnote 116 In Virginia, that same year, delegates expressed confidence in President Grant and the Republicans as they navigated “the dawn of a new era in this Republic.”Footnote 117 And the National Labor Convention endorsed the creation of a Black newspaper to be named The New Era.Footnote 118

At the Southern States Convention of Colored Men in 1871, Jonathan Clarkson Gibbs, prominent African American minister, politician, and the Florida secretary of state told the delegates, “I believe it possible that this Convention may be made the most important gathering of our people that has ever occurred on this continent.”Footnote 119 And J. F. Quarles of Georgia claimed, “We have passed through a revolution which, for intense bitterness, stubborn encounters, and stupendous results, has rarely been equaled, and never surpassed in the history of any people.”Footnote 120 He pushed against the oppression by the white South, imploring, “let us clear away the rubbish of the past.”Footnote 121 The emergence of a new historical moment was obvious to all, but the urgency for political action persisted when conditions did not improve.

It is noteworthy that convention participants do not identify the end of Reconstruction as another critical juncture. There is scant discussion of 1877 as a break in the path of development compared to the many pronouncements about emancipation. Selena Sanderfer finds that support for emigration increased after the removal of federal troops and the subsequent rise in violence against Blacks, but it “was not uniform and was usually reserved for movements within the United States.”Footnote 122 At the first national conference after the Hayes Tilden Compromise, the Report of the Committee on Migration outlined the causes of the new exodus movement:

The colored people of the Southern States have become thoroughly alarmed at the constant attacks on their political and civil rights, not only by legislative enactments and verdicts of courts, but more especially through and by the medium of State constitutional conventions. These conventions have been called in nearly every State once ruled by Republicans, but now under the rule of the Democratic party. In every instance the openly-avowed object for the holding of these constitutional conventions by Democrats is to overturn and repeal all laws passed by Republican conventions or legislatures looking toward the protection of colored people in all of their political, civil, and educational rights.… These Democratic enactments have made the colored people the target for so-called vagrant laws, unjust poll-taxes, and curtailed educational advantages, and all legislation has been toward enfeebling them in all that Republican legislation strengthened and protected them.Footnote 123

The reactionary state constitutional conventions referenced by this report were called by white conservatives in 1870 (Tennessee), 1874 (Arkansas), 1875 (Alabama, North Carolina, Texas), 1877 (Georgia), and 1879 (Louisiana).Footnote 124 As early as 1871, the Meeting of Colored Citizens of Frankfort, Kentucky, drafted a timeline of 116 atrocities committed by white citizens over the previous two and a half years.Footnote 125 Black southerners experienced the end of Reconstruction as a rolling series of failures, which perhaps explains why the Compromise of 1877 and federal abandonment are not discussed as a critical juncture in the debate records.

Some convention delegates, on the other hand, demonstrated optimism, even as the war and emancipation grew more distant. In 1877, Black North Carolinians drafted resolutions that stated, “the disappearance of race prejudice and the growing feeling of confidence and friendships between the races were among the encouraging signs of the times.”Footnote 126 J. C. Corbin of Arkansas told the National Conference of Colored Men in Tennessee two years later that disfranchisement would be “temporary and transitory” because “the spirit of our age, the genius of our Government, the grave evils that follow in its wake, all strongly tend to shorten its duration; so that they that be with us are mightier than they that be against us.”Footnote 127

The sanguinity of the “new era” was illusory for many, however, and they pushed with a new resolve to combat forces of white supremacy. At the same convention, Theo Greene of Mississippi argued, “It is said that the darkest hour is just before dawn; if so let us strive to realize the fact that the present period of our history is about the gloomiest of our experience, and endeavor to fit ourselves for the dawn of a better and brighter day.”Footnote 128 And the report of the committee on the address warned, “We have reached a crisis in the history of the race…. We have submitted patiently to the wrongs and injustice which have been heaped upon us, trusting that in the fullness of time a generous and humane public sentiment would bring to our relief the enforcement of all laws passed for our protection.”Footnote 129 Resistance by whites required Black southerners to continually operate under emergency conditions, from Reconstruction to its failure to the legal and extralegal assaults on civil rights that followed.

Frederick Douglass delivered an address in Louisville to the National Convention of Colored Men in 1883. “We rejoice also that one of the results of this stupendous revolution in our national history … that this change has started the American Republic on a new departure, full of promise.Footnote 130 But he warned of “problems novel and difficult.”Footnote 131 That same year, Douglass told a convention in Washington, DC, “Far down the ages, when men shall wish to inform themselves as to the real state of liberty, law, religion and civilization in the United States at this juncture of our history, they will overhaul the proceedings of the Supreme Court, and read the decision declaring the Civil rights Bill unconstitutional and void.”Footnote 132 He saw that the crisis continued and that while emancipation was a revolutionary moment, white supremacists at every level and in every branch of government would oppose any efforts to move the nation down the path of equality.

On the eve of widespread state constitutional disfranchisement of Black men, confidence about improvement over the previous two decades mixed with fear and determination. An “Address to the Colored People of Kentucky” in 1885 read, “We, your delegates in convention assembled, have pleasure in congratulating you upon the progress you have made in the pursuit of those things which commend you to the world. Your progress is the more gratifying when it is remembered under what circumstances it has been achieved.”Footnote 133 They continued, “the hand of Providence has led you in ways you knew not of, and though opposed by foes without and often betrayed by friends within, to-day you make a showing that has no parallel in history.”Footnote 134 Reverend William J. Simmons, who had once been enslaved but became a scholar, minister, educator, and college president, offered the “grievances of the colored citizens” to the state legislature. He said, “We belong to the South—the ‘New South’… We look to you, the new blood of a new generation, for modifications and innovations. We are moving with the tide. ‘We are heirs of all the ages.’”Footnote 135 Simmons articulated the historical shift and the idea that African Americans were indeed southerners.

In Georgia in 1888, the proceedings indicate a suspicion of reliance on the benevolence of whites. Rev. Charles T. Walker, who was born into slavery but later established Augusta's Tabernacle Baptist Church, warned, “the time has fully come in the history of the colored race when the Negro must no longer be a chattel and a tool.”Footnote 136 Rev. Walker gave voice to the “waiting” facet of Michael Hanchard's “racial time” (wherein Blacks are delayed access to rights and privileges that whites receive first)—“the Negro has been told to wait, don't be hasty. If we are citizens why wait any longer than others, we have proven to the government that we are a peaceable, loyal, law-abiding people.”Footnote 137 He closes with a call to action, “For all time to come let none be more solicitous for our welfare, than we ourselves. Let us crowd our petitions into the national halls of legislations, let us solve our problems, shape our destiny, make for ourselves a history, and take our places in the onward march of progress alongside with the other races of this country.”Footnote 138 Here the rhetoric suggests the present was a critical moment to both control the historical narrative and direct the march into a new, more just South.

2.3 Fighting for the Future

A key component of Hanchard's racial time is “the belief that the future should or must be an improvement on the present.”Footnote 139 And for Du Bois, labor and education rights were integral to democratization of the South after the war.Footnote 140 In this section, I treat labor and education rights separately, though they were often interconnected in the rhetoric of convention participants, who saw both as key to future development and democratization. Almost all conventions addressed these topics, but there were sixteen called explicitly to consider education, teaching, or labor. It is telling that all four education conventions, all three teacher's conventions, and eight of the nine labor conventions were held in the South.Footnote 141 Black southerners were the most vociferous promoters of these rights that they had for so long been denied and that they saw as necessary to the acquisition of other political and social rights.

At the Colored National Labor Convention in 1869, the report of the Committee on Education read in part, “The relations which education sustains labor are, indeed, second in importance only to those which are sustained to it by attributes of life and freedom.”Footnote 142 It continued, “education is the necessary condition of the most efficient labor; and such being the case, it becomes a matter of great moment to colored workingmen to inquire as to their present condition and future prospects in reference to it.”Footnote 143 The 1879 national convention held in Tennessee created a single Committee on Education and Labor rather than separate the issues.Footnote 144 Another gathering that year ordered its “Address to the Colored People of Texas” published in newspapers, including the following proclamations,

First—That by the fruits of our labor the great majority of the finest educated white gentlemen of the past and present generations of the south mainly owe their education and prosperity. Second—That not only in the past, but at the present time, the white people of the south control our labor, and that it would be but a small return to aid our people to educate their children. Third—That the ignorance and abject poverty of large numbers of citizens has, and will ever prove detrimental to the best interests of all classes of citizens and good government.Footnote 145

So, for these delegates, education and labor were not just connected to each other, they were part of the past, present, and future of Southern society.

It is not surprising that Black politicians and activists focused on protecting workers after the Civil War. They recognized the potential for abuse and exploitation of those who had been enslaved. The transformation in Southern economic relationships was not just a move from chattel to wages; it was about who controlled the time of the Black agricultural labor force. A Southern slaveholder explained: “I have ever maintained the doctrine that my negroes have no time whatever; that they are always liable to my call without questioning for a moment the propriety of it; and I adhere to this on the grounds of expediency and right.”Footnote 146 Slaveholders also heavily regulated calendrical time.Footnote 147 And these white men managed the lifetime of Black southerners, from birthdays to age when sent to the fields to reproduction to retirement.Footnote 148 Scholars note the great potential for emancipated men and women to achieve temporal autonomy.Footnote 149 Hanchard writes, “temporal freedom meant not only an abolition of the temporal constraints slave labor placed on New World Africans but also the freedom to construct individual and collective temporality that existed autonomously from (albeit contemporaneously with) the temporality of their former masters.”Footnote 150 The shift from slavery to freedom seemed to promise African Americans new temporal authority, and they saw the right to own land and control their work time as indispensable to securing other rights.

Demands for labor rights appeared soon after emancipation in the Colored Conventions Movement. Virginia delegates in 1865 warned that “your late owners are forming Labor Associations, for the purpose of fixing and maintaining, without the least reference to your wishes and wants, the prices to be paid for your labor,” and then advocated the creation of Black labor associations, “having for their object the protection of the colored laborer, by regulating fairly the price of labor; by affording facilities for obtaining employment by a system of registration, and … to enforce legally the fulfillment of all contracts made with him.”Footnote 151 Later that same year a convention in Arkansas included among its resolutions, “Believing, as we do, that we are destined in the future, as in the past, to cultivate your cotton fields, we claim for Arkansas the first to deal justly and equitably for her laborers.”Footnote 152 And Georgia delegates in 1869 created the State Mechanics’ and Laborers’ Association, as well as local unions, and recommended the formation of auxiliary Workingwomen's Associations.Footnote 153

The final national convention of the 1860s met in Washington, DC, with the specific purpose of promoting labor rights. Delegates to the Colored National Labor Convention demanded vast safeguards for Black workers. In the address titled, “The Relations of the Colored People to American Industry,” they asked for apprenticeships for young African Americans, access to all industries, protection of contracts, and that “for every day's labor given we be paid full and fair remuneration.”Footnote 154 And “Our mottoes are liberty and labor, enfranchisement and education! The spelling book and the hoe, the hammer and the vote, the opportunity to work and to rise.”Footnote 155 The Committee on Education wrote, “the laborer must be a living man, free in all his acts, thoughts, and volitions … the emancipation of slaves was in effect a conversion of capital into labor,” so protection of rights was essential.Footnote 156 There was an appeal to all citizens and workingmen, “every man should try and receive an exchange for his labor, which by proper economy and investment, will, in the future, place him in the position of those on whom he is now dependent for a living.”Footnote 157 And through labor organization, “you will force opposite combinations to recognize your claims to work without restriction because of our color, and open the way for your children to learn trades and move forward in the enjoyment of all the rights of American citizenship.”Footnote 158 Labor rights were indispensable.

The Colored Citizens of Tennessee warned in 1871 that Black agricultural workers were perpetually exploited by whites, threatened by violence from the Klan, and denied protection of the state government. Convict leasing presented a new method of temporal theft: “We shall soon see them [prisoners] hired out to private service by the year as servants and sold on the auction block as slaves for the balance of their time.”Footnote 159 The committee on labor at the Southern States Convention of Colored Men reported, “Capital and labor are now beginning to recognize their mutual relations and dependence on each other. The importance of the development of the resources of the country by the colored men of the South presses itself upon our attention at all times and in all places.”Footnote 160 Treatment of labor was tied to the many contributions of Black southerners to the region's economy, and delegates saw it as an issue of the historical moment. J. F. Quarles of Georgia argued, “This question of labor is one of the most delicate, as well as one of the most pressing questions of the age.… How shall the laborer be justly remunerated? We must impress upon the Southern mind the fact that the time has passed when oligarchy and aristocracy and caste could bear rule.”Footnote 161 In 1879, the National Conference of Colored Men met in Nashville and adopted a resolution, “That the right to labor and to receive wages commensurate with the labor performed are sacred principles underlying the primal foundation of human society.”Footnote 162 These rights were necessary to the break with the past, take advantage of the new beginning promised by emancipation, and improve the future.

Debates in the Colored Conventions Movement also focused on the right to education, something that was not always guaranteed.Footnote 163 Most state constitutions drafted after 1820, however, included a free public education.Footnote 164 Framers in the South resisted such provisions because reading and writing could spread ideas of freedom, foster hope, and encourage rebellion among enslaved people. Reconstruction brought public education to the region.Footnote 165 A review of the state constitutional convention debates reveals that African Americans were crucial advocates for including this right in the fundamental law.Footnote 166 It is therefore unsurprising that participants in the Colored Conventions Movement also placed an emphasis on the issue. Calls for education were often indicative of how Black southerners saw themselves in the flow of time. They had been denied access in the past, so new laws and institutions were immediately necessary in the present to protect the future. And education itself was a vehicle through which African Americans could better understand their own history.

In Charleston in 1865, delegates drafted resolutions connecting education to Black political, social, and economic prosperity. Whereas “knowledge is power,” it was resolved to “solemnly urge the parents and guardians of the young and rising generation, by the sad recollection of our forced ignorance and degradation in the past, and by the bright and inspiring hopes of the future, to see that schools are at once established.”Footnote 167 And the 1865 Little Rock convention included among its resolutions “that we are the substrata, the foundation on which the future power and wealth of the State of Arkansas must be built, and as the future prosperity of the State cannot afford to rest upon ignorant labor, therefore, we respectfully ask the Legislature to provide for the education of our children.”Footnote 168 This statement ties education to past contributions, justice for Black laborers, and future development.

The Freedman's Convention of Georgia explained to the state legislature in 1866 that “you can not in justice with the progress of society and spread of ideas, enact laws for the future by the aspects of the present. A few years will materially change our status, education and wealth.… We therefore trust your honorable body will make laws which will contemplate the future, more than, the present.”Footnote 169 The Colored Men of Kentucky argued that we “must educate our people, and make for ourselves and our posterity undying characters—reputations which will grow brighter as time with rapid whirl rolls on the ages.”Footnote 170 And the Colored People's Educational Convention addressed the people of color of the state of Missouri, “we beg you to lend us your ears. Knowledge is power.… As, in the crucial test of the past, whether amid the haunts of peace, or beneath the fiery baptism of battle, you have done your duty right well and nobly, so we beg you will, in the present and in the time to come, be unswervingly loyal to the sacred principles of American constitutional liberty.”Footnote 171 Temporal metaphors and images link education and progress.

The Colored National Labor Convention connected education to labor and the future. One resolution advocating for free public schools argued that “educated labor is more productive, is worth, and commands, higher rates of wages, is less dependent upon capital.”Footnote 172 The report from the Committee on Education noted that it had been almost two and a half centuries since “since a Dutch vessel landed upon the shores of Virginia the first cargo of human merchandise,” and “through the servile agency thus introduced, and extended also to the adjoining provinces, the eminent agricultural resources of the country were largely developed.”Footnote 173 These debates included the necessity of education, labor rights, and historical narratives about the essential contributions by African Americans to national economic development.

Education was a primary focus at the Southern States Convention of 1871 as well. William Henry Grey told the delegates, “In the country in which I reside, these questions are of vital importance: questions of education, and of the progress of the rising generation. These questions lie near the heart of every colored man in Arkansas, and they are expecting that something will be done, by this Convention, to give an impetus to the education of the rising generation.”Footnote 174 The “Address to the People of the United States” read, “While we have, as a body, contributed our labor in the past to enhance the wealth and promote the welfare of the community, we have, as a class, been deprived of one of the chief benefits to be derived from industry, namely: the acquisition of education and experience, the return that civilization makes for the labor of the individual.”Footnote 175 And the Report on Education and Labor presented the new founding moment: “The sudden emancipation of over four millions of colored men, women and children, naturally brought with it the concomitant disadvantages of centuries of accumulated ignorance.”Footnote 176 Educational progress was tied to the path of development: “We look at the future of our race, on this Continent, as one of only a question of time, as to the, complete success of the realization of our most sanguine expectations, or most devout wishes.”Footnote 177

An 1873 convention in Delaware pleaded for the expansion of public education that had been denied by the state for so many years. The “Address to the People of the State” focused on this topic: “We specially ask now that equal school rights be afforded us. This we do not ask merely as a matter of right, but as a crying necessity—a necessity without which the future of our race appears almost utterly hopeless.”Footnote 178 In 1877, African Americans in both Georgia and Kentucky called Educational Conventions. The delegates similarly connected the right to the future. Prof. J. M. Maxwell told delegates in Kentucky, “I rejoice that the prospect is so bright for the coming of that day when in every county, township, and village of this beautiful and rich Commonwealth the portals of knowledge shall be opened.”Footnote 179 He also associated education with the urgency of the political moment, “The history of the ages that are past has begun to convince the nations of the earth that to make liberal provisions for the education of the people is national economy instead of political extravagance; and never in the world's history has the cause of general education been espoused so universally as at the present time.”Footnote 180

Theo H. Greene spoke on the “Elements of Prosperity” to the National Conference of Colored Men in Tennessee in 1879:

Of all the agencies that serve to further advancement and produce happiness and refinement, education stands first and foremost. Its power and efficacy in the attainment of these has been forcibly exemplified during all ages, and it is an undoubted fact that it will continue to wield this commanding power and influence in shaping the affairs and destinies of nations for all coming ages.Footnote 181

Delegates in Texas that same year adopted resolutions that reflected Greene's observation. “The foundation stone of education and character must be laid in the grand race of life.”Footnote 182 They also tied education to labor rights in their “Address to the Colored People of Texas.”Footnote 183 Temporal framing again moves from the historical moment to labor to the right to a public education.

African Americans continued to argue that education was bound to future prosperity in the final decades of the nineteenth century. The report by the Committee on Education at the 1884 State Conference of Colored Men of Florida read, “The general diffusion of knowledge is one of the most powerful agencies of human progress.… It affords the benefits to be derived from the arts and literature of the world, past and present.”Footnote 184 The following year, an “Address to the Colored People of Kentucky” asserted that “Education is most important factor in the solution of the problem that is before you.”Footnote 185 Georgia delegates in 1888 spoke on behalf of the Blair Education Bill, “No people should be more interested about federal aid to education than the colored man. It is a lever than will lift him from the grave of ignominy and hatred and give him a prominent place on the stage of progress. The time has fully come in the history of the colored race when the Negro must no longer be a chattel and a tool.”Footnote 186 They also believed that without education “the future will present insurmountable difficulties.”Footnote 187

Professor Hugh M. Browne, an educator, minister, and civil rights activist, spoke to the Hampton Negro Conference in 1899. Topics covered included the inadequate facilities, the lack of teachers, and the failure to agree on the type of education needed by Black southerners—literary or industrial. Browne related schooling to both the future of the race and the future of the region. “I believe that this matter of education is the vital feature connected with the development of the South.”Footnote 188 He advocated for improvement of education so that Black southerners might contribute to the growth and progress of their native land. The temporal feature of this foundational right was present in 1899, as it was at the end of the war. Resistance by the white South and efforts to keep the labor force ignorant made Black education an ongoing crisis that required continual attention.

3. Conclusion

The Colored Conventions Movement was a vital part of nineteenth-century American political development. Black southerners assembled in the very states where they had recently been enslaved to demand recognition as citizens and equal treatment under the law. The delegates illuminated the power of time as a tool for individuals and social movements. They used the statements, resolutions, and addresses of this public forum to advocate on their own behalf. Time is a constant theme of the movement—not just change over time or the passage of time, but the perception of time, and ultimately the use of time and temporal language as a political tool. Many of their efforts failed initially, but they did not quietly accept subjugation and abuse. During the Civil Rights Movement, Black leaders again used the past and present to demand a different path into the future, building on the rhetorical work of their activist predecessors.

The most prevalent temporal tool in the convention debates was the use of the past to correct the distorted historical record. Participants did not just recount history from a Black perspective; they forced the white public to confront the brutality of slavery and accept the many contributions that African Americans had made to the nation's economic development and military efforts. Their timeline established a path from suffering and degradation to land cultivation to military service to full citizenship. The conventions gathered during the same period in which representatives of the white South were telling the story of benevolent slaveholders, white supremacy, ungrateful and ignorant Blacks, evil Republicans, failures of Reconstruction, white victimhood, a lost cause, an old South, and the promise of a new one. It was thus imperative that Black delegates engage with the past while advocating for the future.

The second temporal tool was the identification of emancipation as a new founding moment and the present as an ongoing moment of crisis. In a 1967 speech criticizing the Vietnam War, Martin Luther King, Jr. articulated a similar vision of the present wherein political action was necessary to define the path of future development:

We are now faced with the fact that tomorrow is today. We are confronted with the fierce urgency of now. In this unfolding conundrum of life and history there is such a thing as being too late. Procrastination is still the thief of time. Life often leaves us standing bare, naked and dejected with a lost opportunity. The ‘tide in the affairs of men’ does not remain at the flood; it ebbs. We may cry out desperately for time to pause in her passage, but time is deaf to every plea and rushes on. Over the bleached bones and jumbled residue of numerous civilizations are written the pathetic words: ‘Too late.’Footnote 189

The delegates of the Colored Conventions Movement also recognized that their actions would affect the legal and political path forward and whether African Americans would gain essential rights. The speeches, writings, and accounts show that they saw the present as a time of transition that would shape tomorrow—an example of individuals within a social movement recognizing a critical juncture in history and attempting to change the path of development. They would not “wait” any longer for equal treatment; they would instead upend the control of time by whites.Footnote 190 And they used the language of time in their advocacy.

For Black southerners, labor and education rights were foundational. Without the ability to earn a living and enlighten the mind, participation in politics through voting and officeholding would be impossible. The convention debates and documents show that African Americans recognized that the shift from slavery to freedom (real freedom) would require education and protection of agricultural laborers from the white landholders of the South. Black southerners were previously denied education to their detriment and to the advantage of whites, so the right to a free public education was critical for the future of Blacks in the South and in America. The struggle over how a new free economy might operate required Blacks to think about both time and space. Could they acquire land, and if they worked the land of others, could these men and women get paid what they deserved? If not, should African Americans leave the South? The principal way delegates used temporality to advance labor and education rights was by arguing that these rights were necessary in the present to gain more opportunity in the future. There were, however, secondary temporal dimensions to each that appeared as well—labor rights meant individual control over work time, and a free public education was a tool to better understand the past. Convention transcripts repeatedly show the conceptualization of a timeline moving from the ignorance and weakness of slavery to the knowledge and power of independence.

These temporal themes were sometimes joined in the dialog of convention debates. In 1872 at the National Convention of Colored Citizens in New Orleans, Alonzo Jacob Ransier of South Carolina tied together control of the historical narrative, urgency of the present moment, and the rights that would be essential for the future: