Introduction

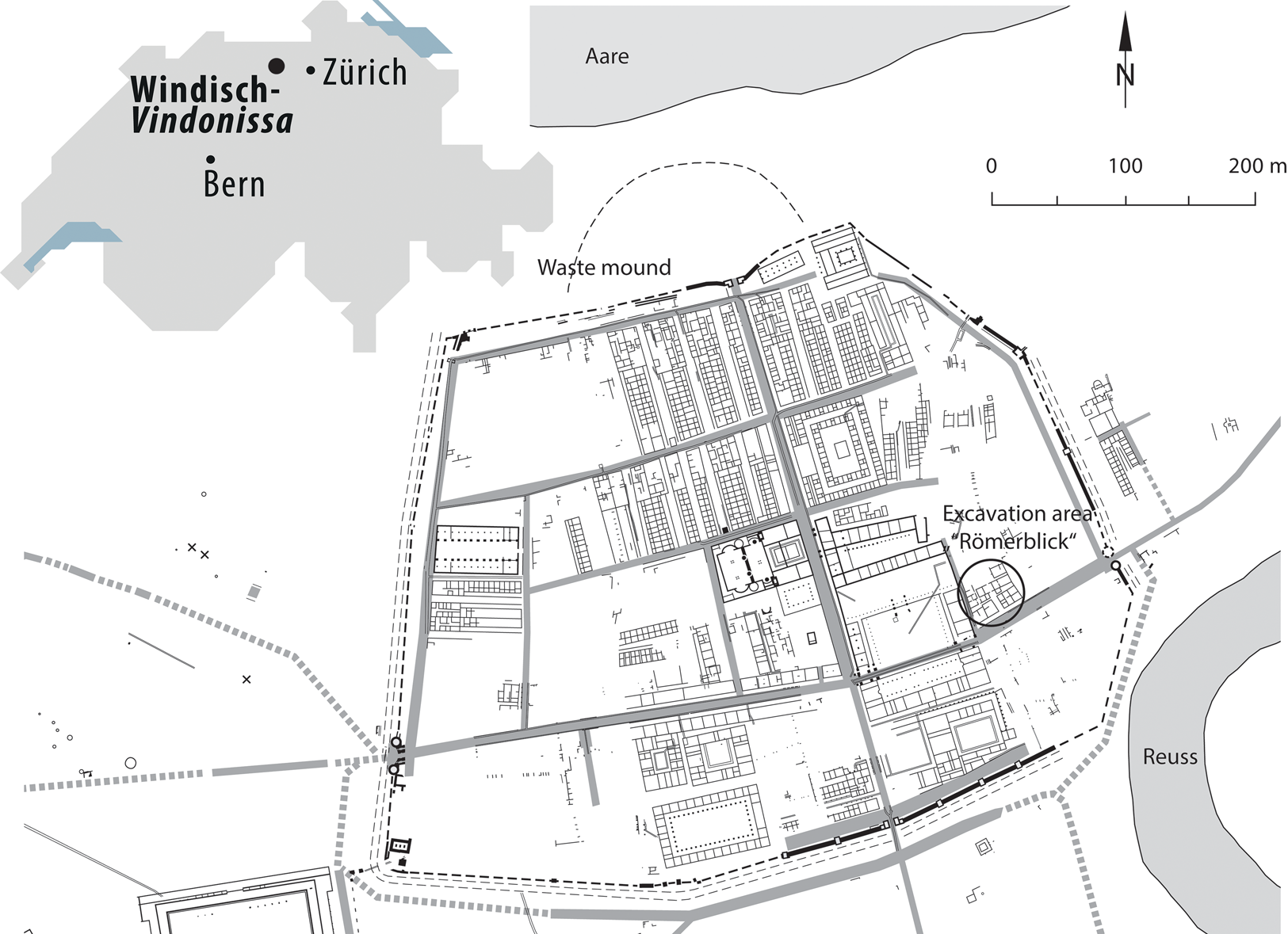

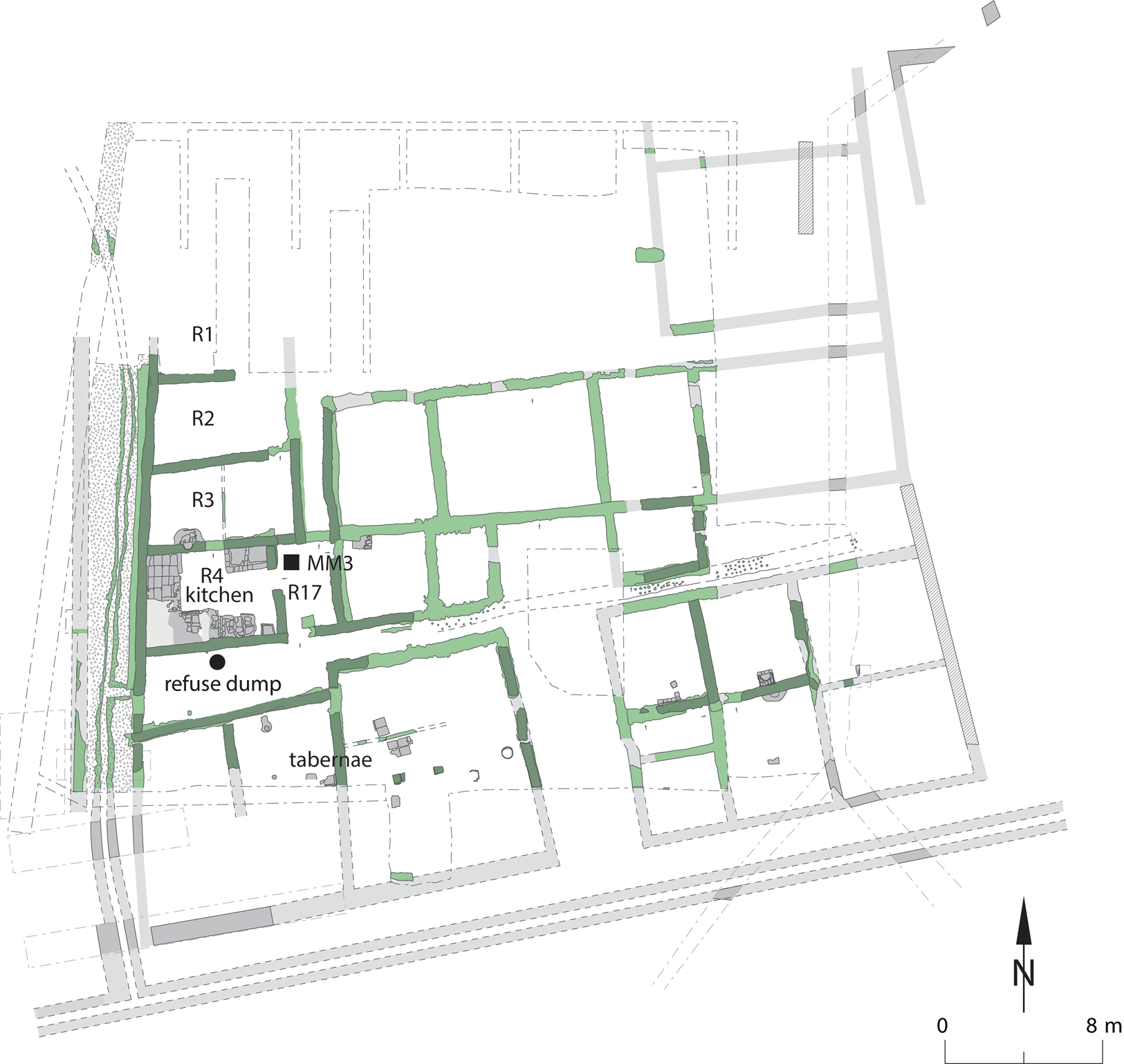

Vindonissa (Windisch, Canton Aargau, Switzerland) is the only Roman legionary camp in the territory of modern Switzerland (Fig. 1). The camp was built around 14 CE and was occupied successively by the 13th (legio XIII Gemina), 21st (legio XXI Rapax), and 11th legions (legio XI Claudia Pia Fidelis).Footnote 1 The 11th legion abandoned Vindonissa under Trajan in 101 CE. The civil settlement continued in use until Late Antiquity. In the Flavian period (ca. 69–96 CE), a major reorganization of the eastern part of the legionary camp was carried out, and a peristyle house of at least 570 mFootnote 2 was erected (Figs. 2 and 3). In a later modification phase, a large kitchen was installed in the building. The building was abandoned in or around 100/101 CE during the withdrawal of the 11th legion.Footnote 3

Fig. 1. Map of the Vindonissa Roman legionary camp (situation in the 1st c. CE) with the excavation area “Windisch-Römerblick” 2002–2004 marked with a black circle (1:5000). (© Kantonsarchäologie Aargau/S. Dietiker, M. Flück.)

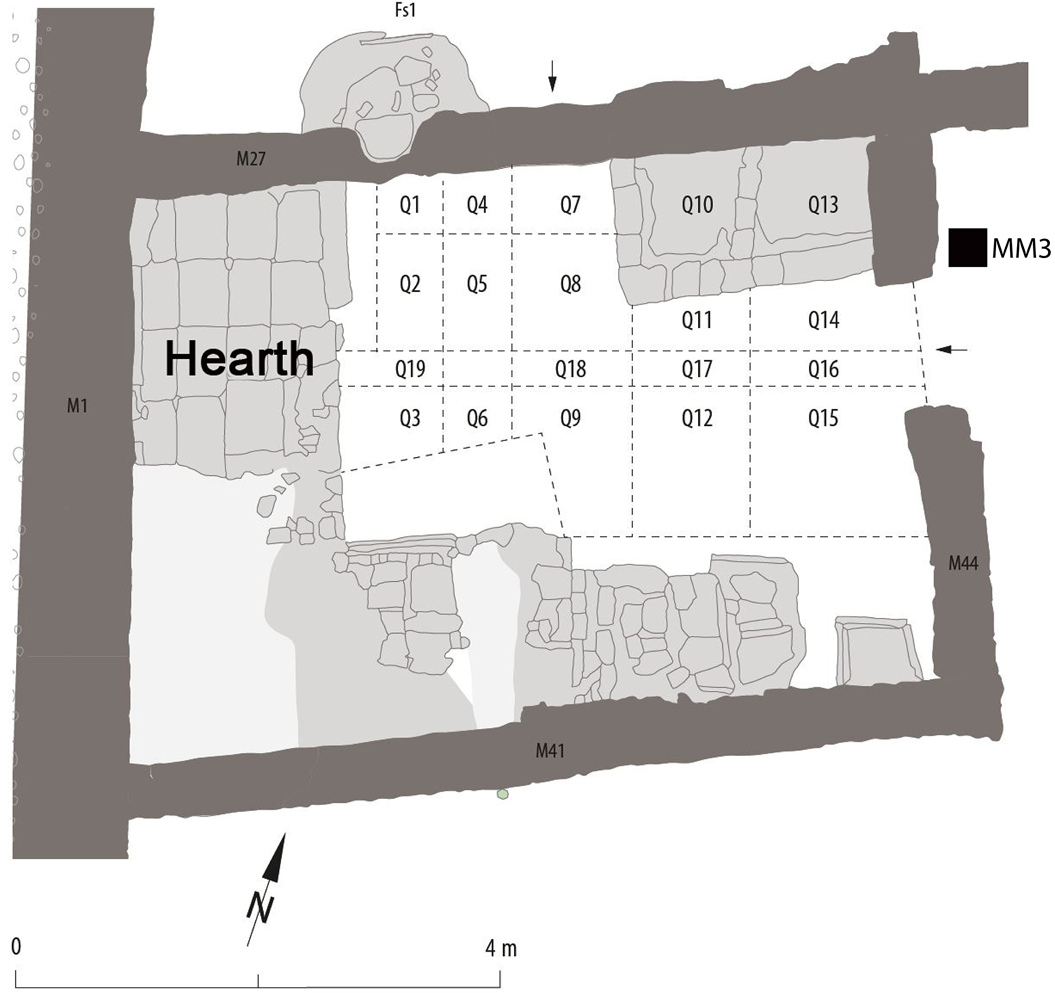

Fig. 2. Context plan of the peristyle house and location of the kitchen (R4), the anteroom (R17), the adjoining room (R3), other rooms (R1 and R2), and the dead end with the refuse dump (between the peristyle building and tabernae). MM3: micromorphology sample. (© Kantonsarchäologie Aargau/S. Dietiker, M. Flück.)

Fig. 3. Bird's eye view of the excavated kitchen (R4), anteroom (R17), adjoining room (R3), and the dead end with the refuse dump. (© Kantonsarchäologie Aargau/D. Wälchli.)

During excavations in 2002–2004, an area of 900 m2 was examined. An interdisciplinary post-excavation project was realized in several stages between 2011 and 2020. Several Roman features were discovered, including parts of the peristyle house with its exceptionally well-preserved kitchen (Fig. 1). The interdisciplinary evaluation and synthesis of the whole excavation can be consulted in the monograph published by Flück et al. in 2022.Footnote 4 In this paper we focus on the study of animal bones,Footnote 5 seeds and fruits,Footnote 6 and wood charcoal,Footnote 7 and on micromorphologyFootnote 8 to investigate food processing, cooking habits, and also activities of maintenance and waste disposal in the Mediterranean-style kitchen. In this article, we use the term “Mediterranean-style kitchen” to refer to a room that was used specifically for food preparation and had a large, raised hearth as its most prominent feature. South of the Alps, these raised hearths were part of the standard equipment of urban Roman domus, for example, in Pompeii or Herculaneum, and are regarded as typical elements of Italic-Mediterranean cuisine and dining.Footnote 9 Due to their large cooking surface, different cooking methods could be performed simultaneously and complex dishes prepared.

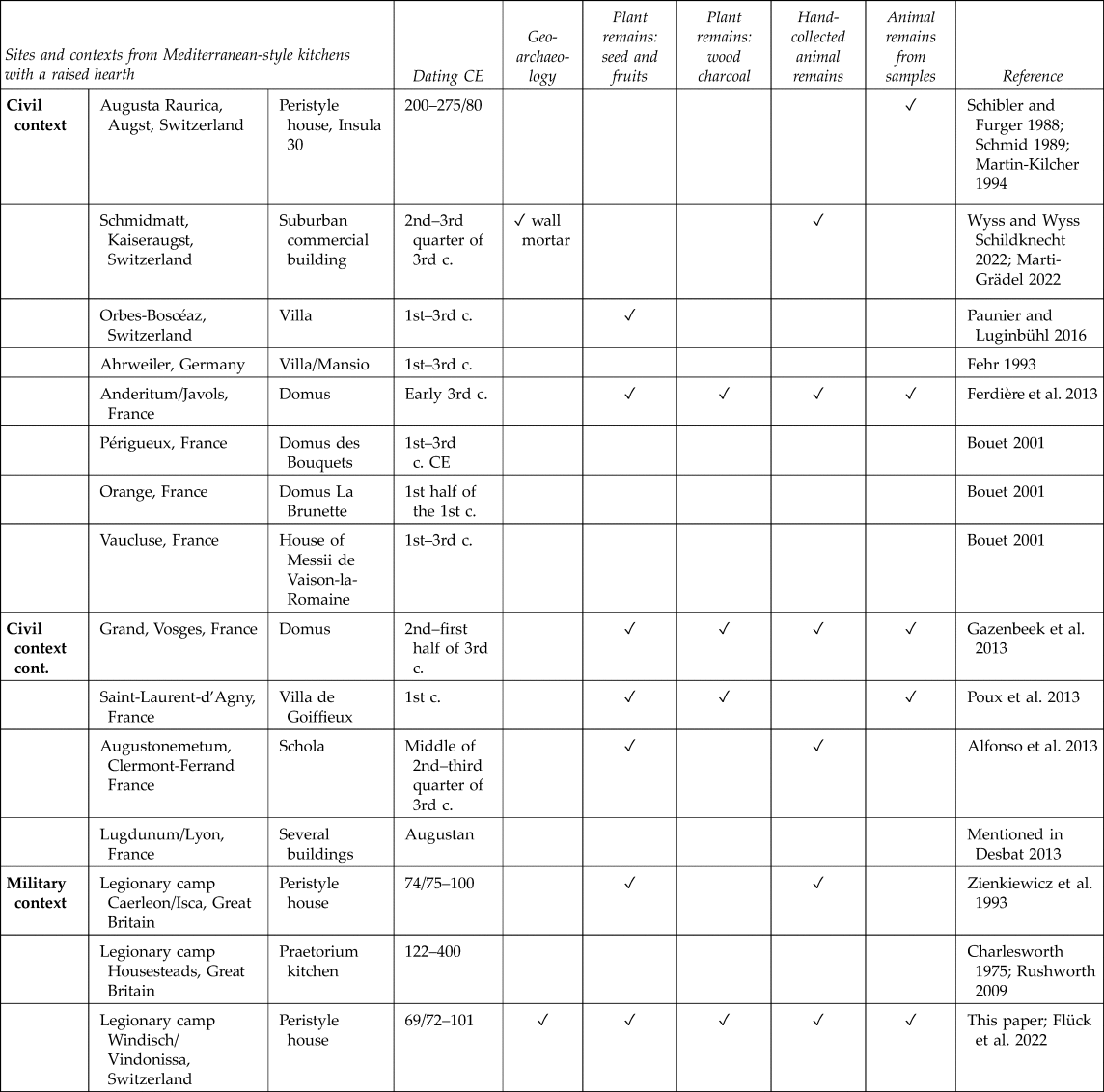

Using the example of the Vindonissa peristyle house kitchen, we will address the frequently asked question about the definition of “luxury food” and what can be said on the basis of diet about the social status of consumers. For this purpose, the archaeobiological data of the Vindonissa kitchen was compared to archaeobiological data from other Mediterranean-style kitchens. In this paper we choose for our comparison the rare examples found in the northwestern provinces, which have so far been discovered mainly in the rich domus of the larger cities or in villae rusticae dating between the 1st and 4th c. CE (Table 1).Footnote 10 Others were discovered in the legionary camp of Caerleon/Isca and Housesteads (UK). The peristyle house kitchen in camp Vindonissa now joins this short list.Footnote 11

Table 1. Kitchen features from sites in the northwestern provinces.

Archaeological structures and findings

The peristyle building complex – most probably two-storied – was at least 36 m by 30 m in size and consisted of adobe brick walls standing on massive plinth walls (Fig. 2). It had an internal courtyard of about 173 m2 (peristyle), similar in size to the peristyle in the “house of the Vettii” in Pompeii.Footnote 12 The building impresses with some outstanding elements such as an entrance portal of cast stone architecture, a supply of running water, and wall paintings.Footnote 13 It is located in a prominent spot in the immediate vicinity of the headquarters building (principia) in the camp.Footnote 14 With floor space of around 700–800 m2, it may be characterized as one of the largest residential buildings within the camp in the Flavian period.Footnote 15

The kitchen (R4) of the peristyle house was about 26 m2 in size and was located in the southwest corner of the building. It had a separate entrance on the southern side that led to a narrow dead end street between the south face of the peristyle building and a row of buildings, probably tabernae, opposite it (Figs. 2–3). This dead end street consisted of a 0.5 m-thick layer of loamy and gravelly occupation deposits. A concentration of fragments of pottery and glass vessels, bones, and wood remains suggests that the area directly in front of the kitchen was used as a refuse dump.Footnote 16

To the east, an anteroom (R17) connected the kitchen to the other rooms of the building.Footnote 17 On the kitchen's northern side, another adjoining room (R3) was found that was equipped with a coarse gravel mortar floor and a simple ground-level fireplace. The separate entrance to the kitchen and its adjoining rooms implies that servants were employed here.Footnote 18 The floor of the kitchen space and of the anteroom (R17) consisted of layers of loam, blackened by ash and charcoal. A freshly minted dupondius of Trajan from the most recent loam floor indicates a terminus post quem of 98 CE.Footnote 19

The most important piece of equipment in the kitchen was an L-shaped, raised hearth, installed along the western and southern outer walls. The 0.6–0.8 m-high substructure was made of clay bricks, and a working surface of 9.8 m2 was formed by fired tile slabs. The large hearth makes it clear that food for a household of many people was prepared.Footnote 20 In the kitchen's southern part, it included a small, lowered platform (1.8 m2) that probably served as a storage surface, as numerous fragments of ceramic vessels, some of them large in size, lay on and in front of it.Footnote 21 An oven is not present.

The ceramic assemblageFootnote 22 in the kitchen, the two adjoining rooms, and the refuse dump comprised over 400 vessels. Most were found in the refuse dump, and they consisted mainly of cooking vessels, including (military) cooking pots, cooking bowls, and also a few plates and tripods, storage vessels, and multifunctional pots. Serving bowls and jugs, eating and drinking utensils, glass vessels, and terra sigillata (imported from southern Gaul) were rare. Furthermore, the remains of a large number of amphorae (MNI = 125) were found, which were used to store various contents.Footnote 23 The imported foodstuffs included wine from southern Gaul, olive oil from the Iberian Peninsula, fish products from the southern coast of the Iberian Peninsula, decanted in central Gaul, and even pickled southern fruits from North Africa and Palestine.Footnote 24 Utensils such as millstones and metal finds (vessels, grates, or skewers) are almost completely missing: only two knives, one of them a large kitchen knife, probably a butcher's knife,Footnote 25 remained in the kitchen. The extensive pottery inventory and the high number of amphorae suggest a household of well over 10 inhabitants.Footnote 26

Micromorphological and archaeobiological approach: methods

Micromorphological studies

For our micromorphological studies, a 21 cm-high soil monolith was extracted from the stratigraphy in the kitchen's anteroom (R17) during archaeological fieldwork (Sample MM3, Fig. 2). Sample preparation was performed at IPAS (Integrative Prehistory and Archaeological Science, University of Basel, Switzerland) using the method of Courty, Goldberg, and Macphail.Footnote 27 Four petrographic thin sections (30 microns) were prepared and studied under a binocular and a polarizing microscope (magnification 8 – 1000x) (Fig. 3).Footnote 28

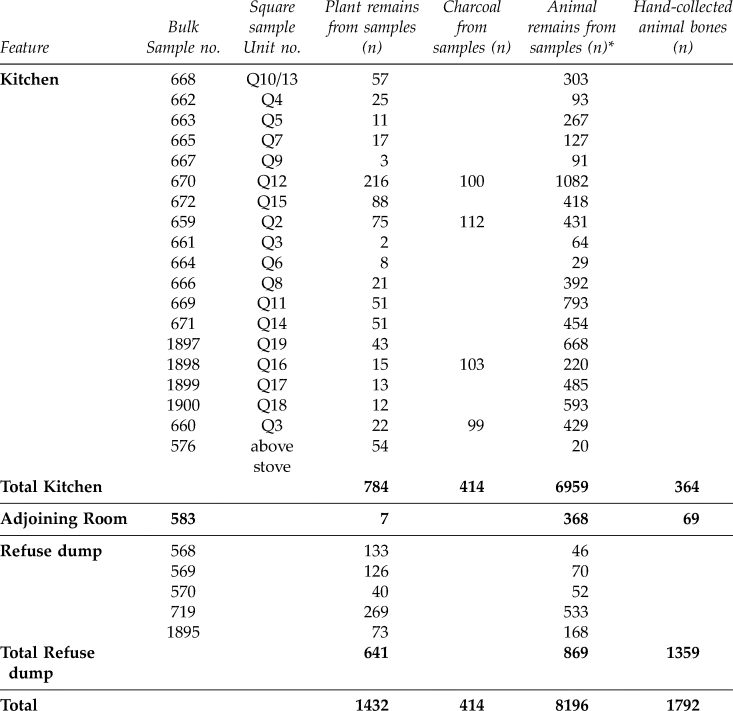

Sample strategy and processing for archaeobiological analysis

Bulk samples were taken for the analysis of archaeobotanical (seeds/fruits and charcoal) and microfaunal remains (Table 2). The kitchen's compacted loam floor was systematically sampled using a grid of 19 squares (Fig. 4); further samples were taken from a layer above the hearth and from the refuse dump.Footnote 29 All samples were processed at IPAS using the wash-over method:Footnote 30 This technique involves washing the sediment and separating the organic from the inorganic material. Sieves with mesh sizes of 4, 1, and 0.35 mm were used. A total of 188.3 liters of sediment was processed.

Table 2. Numbers (NISP) of analyzed plant, charcoal, small animal remains, and hand-collected animal bones per sample, feature and unit. *Small animal remains include fragments of bird eggshells (n = 833).

Fig. 4. Sampling grid of 19 sample fields (Q1–Q19) from the kitchen floor (kitchen_Sp2.2). MM3: micromorphology sample. (Adapted from Flück et al. Reference Flück, Lippe, Meyer-Freuler and Streit2022.)

Archaeobotany: seeds/fruits and wood charcoal

Plant macro remains were analyzed using a Wild M3Z binocular microscope with a 6 to 40-fold magnification. Identifications of the plant material (seeds, fruits) were checked against the modern seed reference collection at IPAS. The botanical nomenclature follows Aeschimann and HeitzFootnote 31 for wild plants and Zohary et al. for cultivated plants.Footnote 32 The resulting data were stored in the ArboDat database.Footnote 33 For the evaluation and interpretation of the plant spectrum, the density of plant remains (number of items per liter) was calculated. The analysis of charred wood was performed on four selected samples from the kitchen's floor (Table 2). Anthracological identification was carried out with a Leitz Laborlux 12ME microscope and using the identification key of Schweingruber.Footnote 34 A sub-sample of 100 charcoals per sample was examined, corresponding to proportions of approx. 8–27% of the material.

Archaeozoology

Large animal bones were hand collected from the kitchen floor and the refuse dump during fieldwork.Footnote 35 To recover the small animal remains, the 4 mm and 1 mm inorganic and organic fractions from the sieved bulk samples were sorted under a Leica MZ6 binocular microscope (magnification ⫻6-⫻40). Due to the abundance of animal remains in the samples from the kitchen, subsamples were examined.Footnote 36 Species were identified using the animal bone reference collection at IPAS. Species identification of the faunal assemblage followed the methodological approach described in Deschler-Erb and Schröder Fartash Reference Deschler-Erb, Schröder Fartash and Rychener1999.Footnote 37 Data acquisition and analysis was carried out using the database OSSOBOOKFootnote 38 and Excel.

Micromorphological and archaeobiological approach: outcome

Micromorphology

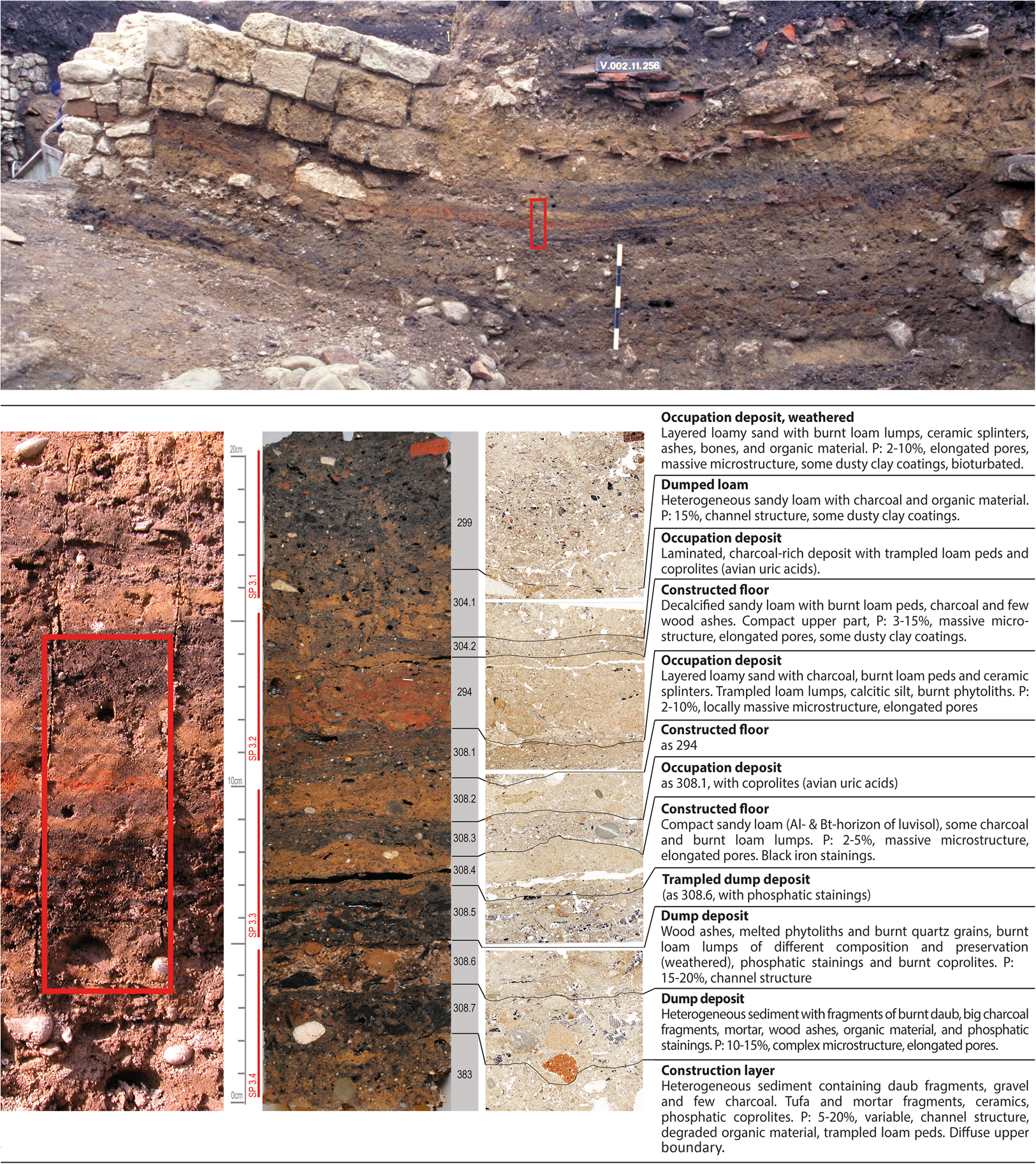

The micromorphological sample MM3 (for location, see Figs. 2 and 4) from the kitchen anteroom (R17) gives an insight into a distinctive stratigraphic sequence, dominated by a succession of multiple loam floors with associated dark-colored occupation deposits. Figure 5 presents the geoarchaeological results, showing the original stratigraphy, a view of the polished block, and the scanned thin sections. At the base of the stratigraphy, a heterogeneous dump (323) indicates earlier construction activities. It is covered by layer 308, which can be subdivided into seven levels. The basal levels 308.7 to 308.5 mainly consist of burnt daub, mortar fragments, charcoal, and weathered ashes. The composition of this layered dump points to a conflagration event followed by renovation activities. The next layer (308.4) represents a 1 cm-thick beaten earth floor, probably made up of burnt and recycled daub. On that surface, trampled charcoal, sand, ceramic splinter, and bird coprolites (avian uric acidFootnote 39) accumulated (308.3). The calcitic silt fraction probably stems from wood ashes. This compacted trampled deposit can be attributed to kitchen activity. A second earthen floor (308.2) and an associated trampled occupation deposit (308.1) comprising charcoal, phytoliths, and burnt loam lumps follows. Layer 294 represents another constructed loam floor made of recycled loam lumps overlain by a loamy and charcoal-rich occupation deposit with remains of avian uric acid (304.2). These special salts stemming from bird excrement are only preserved in a protected, dry environment (indoors). Their presence in the context of a kitchen may indicate food preparation activities, probably slaughtering and gutting, or that birds were kept here for some time. The uppermost layer (299) represents a thick, horizontally bedded occupation deposit, which was overprinted by post-sedimentary processes (bioturbation) after the building was demolished. In summary, micromorphological features, such as horizontal bedding, absence of clay coatings, excellent preservation, presence of avian uric acids, and the existence of beaten floors, indicate a roofed area. At the same time, the floors are characterized by intense human activity and several renewals.Footnote 40 The trampled ash and charcoal deposits from nearby fireplaces have been repeatedly sealed due to the construction of successive loam floors.

Fig. 5. Profile, polished slab and thin section scans with results of micromorphological study, MM3 Room 17. The stratigraphy shows basal dumps, overlain by a succession of loam floors and occupation deposits related to the use of the kitchen. Height of the polished slab: 21cm. (P. Rentzel.)

Archaeobotany: seeds and fruits

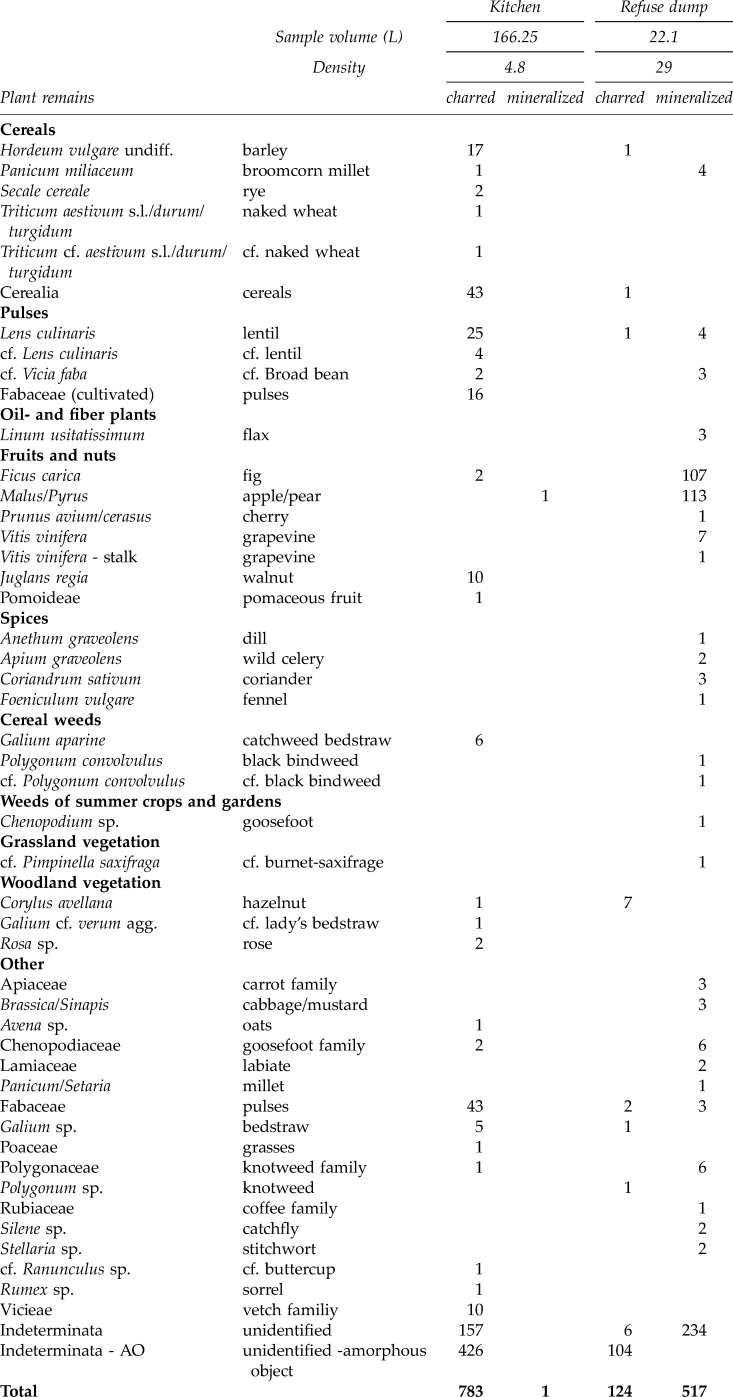

The 19 samples from the kitchen floor (Q1–Q19, Fig. 4) yielded 784 plant macro remains (Tables 2 and 3). Except for one mineralized find, all remains are charred. More than half of the plant macro remains are classified as indeterminate charred amorphous objects (CAO, see below) (n = 426). In addition, one quarter could only be identified to species level, or not at all, due to excessive fragmentation and poor preservation (n = 222). The density of plant remains is generally low, all samples having less than 12 items per liter of sediment. Among the identified plant remains, cultivated plants are most abundant (at least 15 different plant taxa) with cereals and pulses producing the majority of the remains (respectively, 65 and 47 of 135 remains). Barley grains (Hordeum vulgare) dominate the cereal spectrum, but single grains of broomcorn millet (Panicum miliaceum), naked wheat (Triticum aestivum/durum/turgidum), and rye (Secale cereale) are also present. Chaff remains were not recovered. Mainly lentil (Lens culinaris) and possibly broad bean (cf. Vicia faba) represent the pulses. Fruit and nuts are scarce, although there are some remarkable finds of fruit pulp fragments of fig (Ficus carica) and presumably apple (cf. Pomoideae), as well as some shell fragments of walnut (Juglans regia). Spices are not found. Wild plants (seven taxa) represent a very small part of the plant remains, of which the majority could not be determined in detail. The high number of CAOs recovered is remarkable. Although a precise identification of the CAO is not possible in most cases, it is assumed that they represent charred fragments of fruit pulp and/or processed food (e.g., bread, porridge).

Table 3. Overview of the archaeobotanical finds from the kitchen and the refuse dump.

Among the samples from the kitchen floor, there are no significant differences in density, composition, or distribution of plant remains. Hence there is no indication of specific activity areas based on the archaeobotanical findings. The high degree of fragmentation and the limited number of botanical remains could, however, indicate that the floor was heavily used and kept clean.

The five samples from the refuse dump yielded 641 seeds and fruits. Apart from fragments of processed food and/or fruit pulp, hardly any charred remains were found; the majority of the plant macro remains are preserved through mineralization.Footnote 41 The density of plant macro remains is slightly higher than on the kitchen floor and lies between 8.6 and 80 items per liter of sediment. In each of the five samples, the composition of plant remains is nearly the same. A broad range of cultivated plants has been identified, including mainly fruits such as fig, apple/pear (Malus/Pyrus) and grape (Vitis vinifera) as well as cereals (broomcorn millet), pulses (lentil and broad bean) and several spices: dill (Anethum graveolens), celery (Apium graveolens), coriander (Coriandrum sativum), and fennel (Foeniculum vulgare). Wild plants are rare. In addition, a large part of the mineralized remains could not be determined in detail due to poor preservation. The archaeobotanical analysis of the refuse dump indicated the presence of waste of different origins. The predominance of small-seeded food plants, the almost complete absence of large-seeded food plants such as cereal grain, and also the presence of mineralized concretions indicate the presence of fecal matter. The charred fragments of processed food and/or fruit pulp are likely the remains of cooking/baking activities.

Archaeobotany: wood charcoal

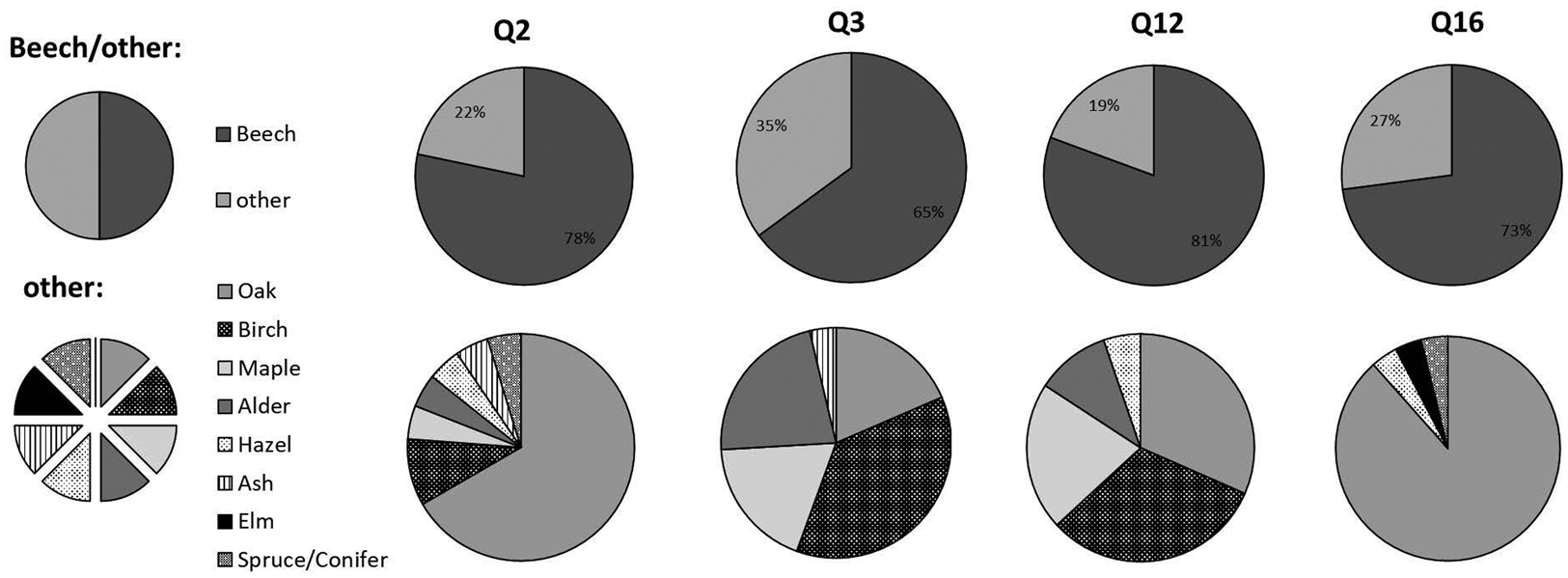

The charcoal spectrum is very diverse; in total, nine wood taxa were identified in the four studied samples of the kitchen floor (Fig. 6). They consist of eight broadleaf/deciduous taxa and one coniferous wood taxon. The charcoal spectrum is dominated by beech (Fagus sylvatica) (65%), followed by oak (Quercus sp.) (11%), while birch (Betula sp.), maple (Acer sp.), alder (Alnus sp.), hazel (Corylus avellana), ash (Fraxinus excelsior), elm (Ulmus sp.), and the conifer species spruce (Picea abies) show proportions of less than 5%. A further 11% of the charcoal fragments remained unidentified. Between samples, there are differences in the taxa (Fig. 6) and also in average weight (in Q12 the average weight per charcoal was 127 mg, in Q2 only 14 mg). These differences are possibly caused by coincidental distribution (cleaning, trampling). While all the broadleaf taxa can be considered local vegetation around Vindonissa, it is to be expected that spruce grew at higher altitudes or in specialized places due to competition with other trees.Footnote 42

Fig. 6. Percentages of red beech wood and other woods in the four samples from kitchen floor sample fields, square meters Q2, Q3, Q12, Q16. (A. Schlumbaum/S. Häberle.)

Archaeozoology: small animal remains from bulk samples

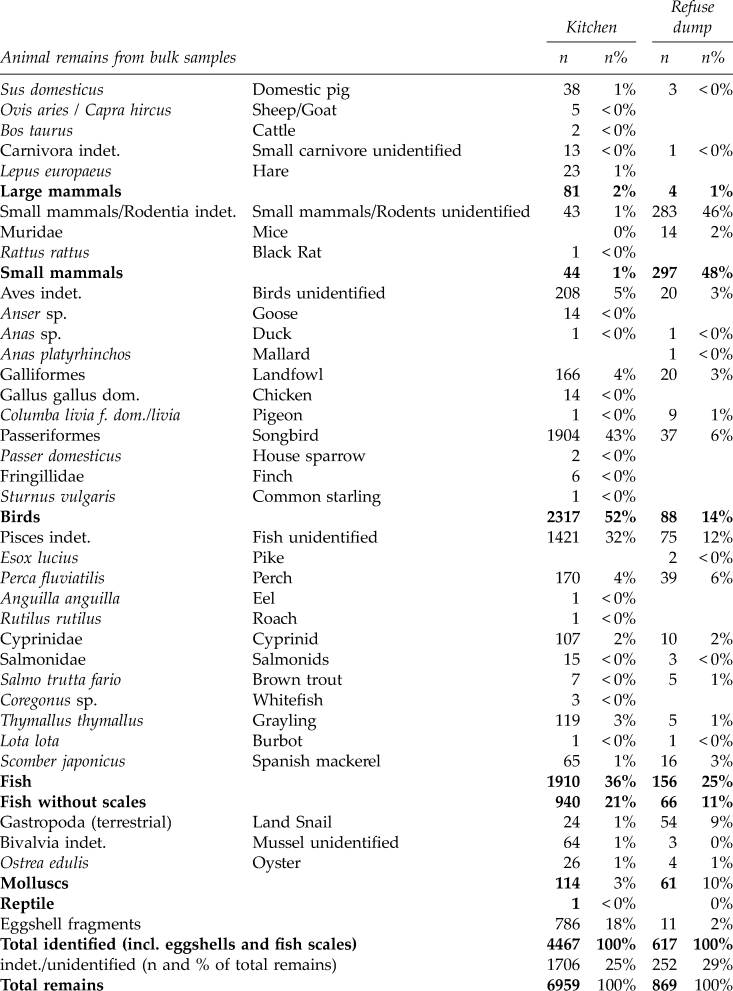

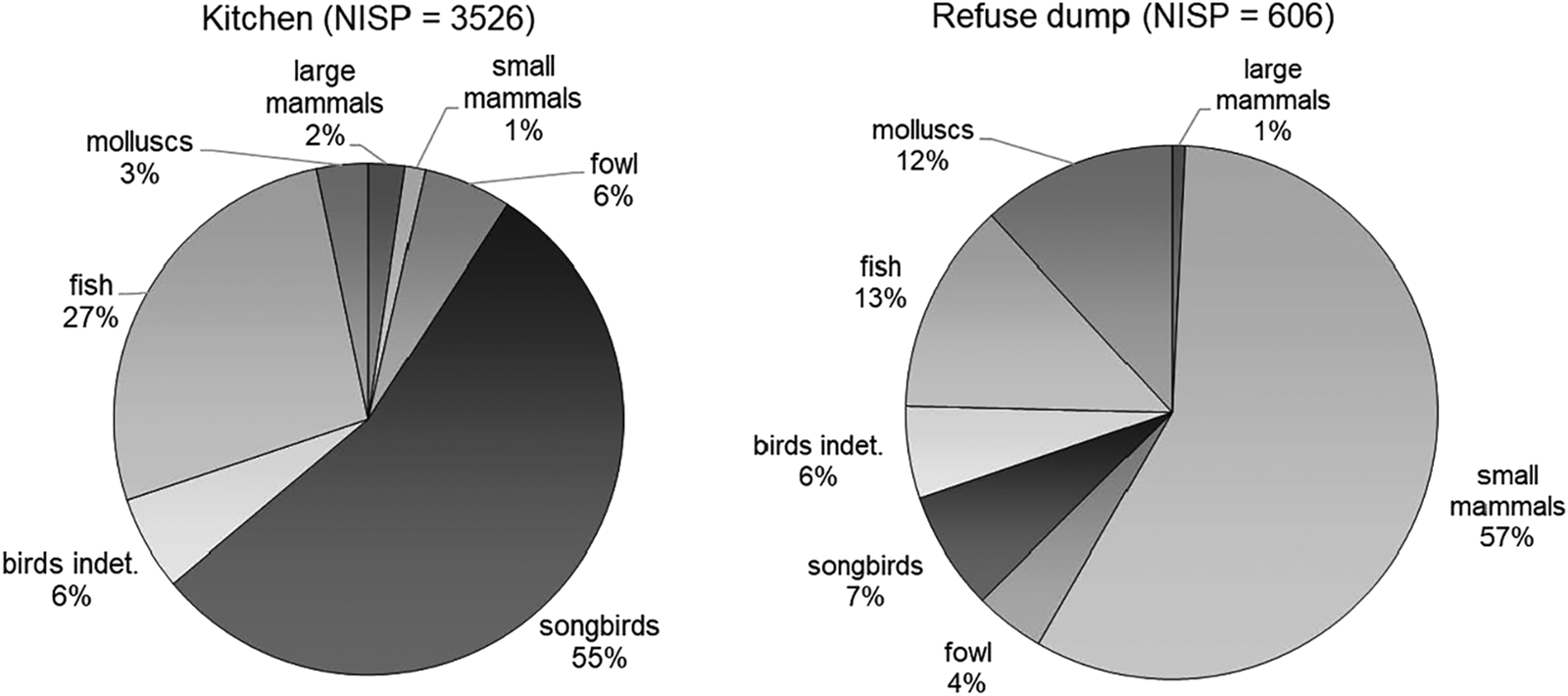

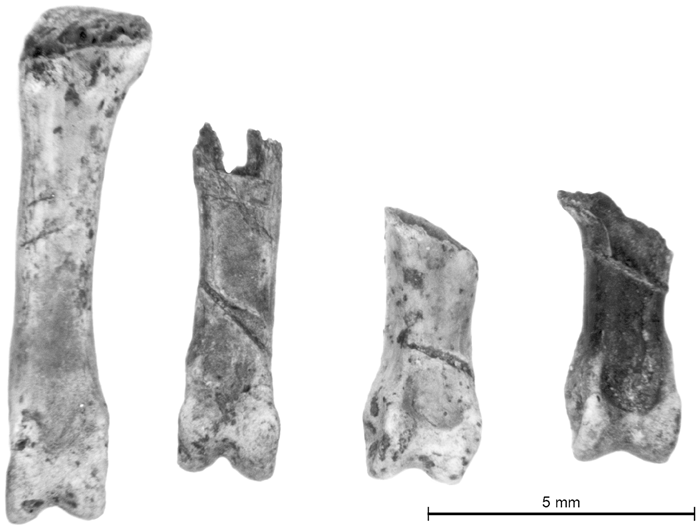

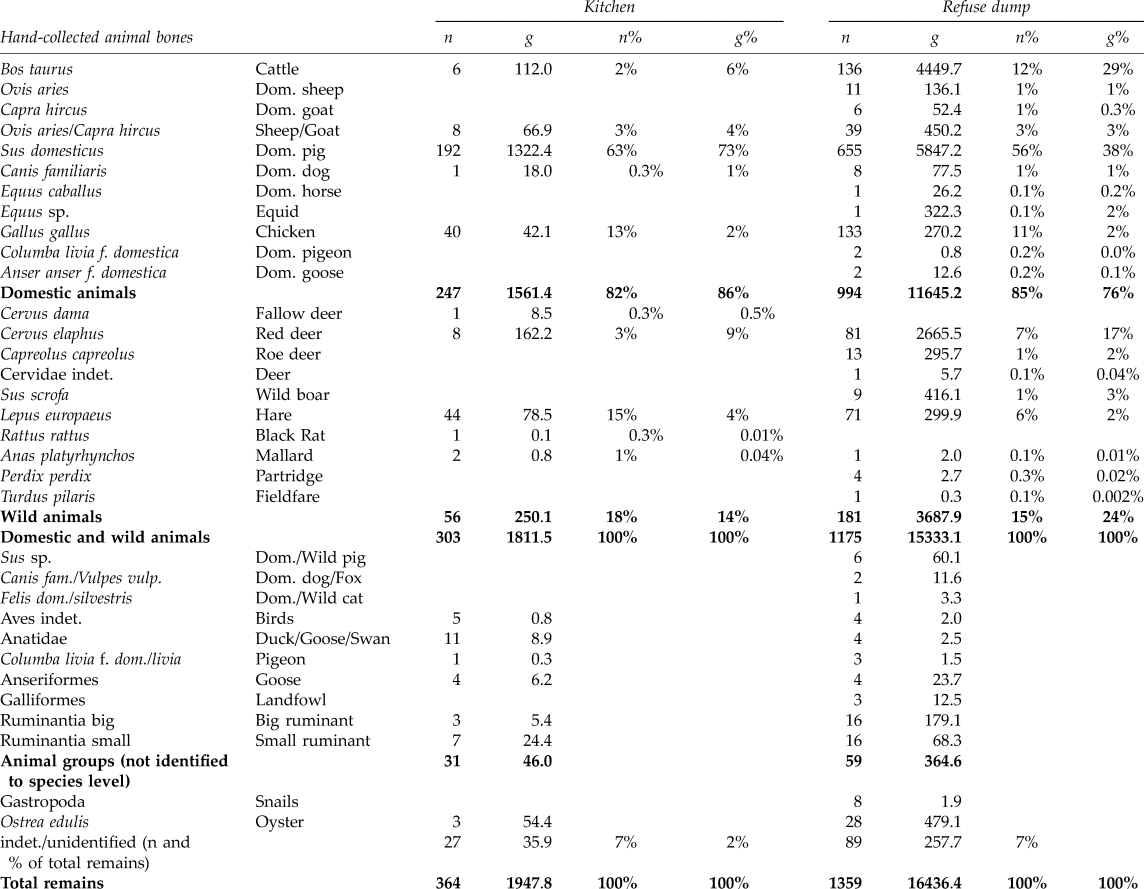

A total of 6,959 animal remains were retrieved from 19 bulk samples from the kitchen floor, of which 5,253 could be further identified. The density is high, with 366 remains per liter, also related to the high number of fish scales, fin rays, and eggshells.Footnote 43 The remains are mostly unburnt bones from fowl, songbirds and other birds; fish; large and small mammals; and shell fragments from molluscs (Table 4, Fig. 7). Songbird remains were counted most frequently (55%), and foot bones are the most represented skeletal part (for songbirds: 76%, for fowl: 35%), many of them with cut marks in locations where the feet, which do not have any meat on them, could have been detached prior to cooking (Fig. 8). The second most common animal group in the kitchen is fish (27%). Highly fragmented and often unidentified scales (63%) and fin rays (26%) are abundant, while vertebrae (8%) and head bones (2%) are rare. Due to the composition of the fish material, only 20% could be further identified to family or species level. Apart from 65 Spanish mackerel bones (Scomber japonicus Footnote 44), several freshwater species could be identified, including salmonids (brown trout [Salmo trutta fario], whitefish [Coregonus sp.], grayling [Thymallus thymallus]), and cyprinids (roach [Rutilus rutilus]), as well as perch (Perca fluviatilis), eel (Anguilla anguilla), and burbot (Lota lota). Shell fragments of oyster (Ostrea edulis, n = 26) have also been identified. Only a few small mammal remains, most probably muridsFootnote 45 and rat (most likely black rat [Rattus rattus]) have been counted. There are slight differences in the horizontal distribution of the remains (e.g., bird, freshwater fish, mackerel, and oyster accumulations in Q 11, 12, 17, and 19, see Figs. 2 and 4). However, it is not clear whether this pattern is a coincidental distribution related to cleaning the floor and trampling or whether it indicates specific activity areas.Footnote 46

Table 4. Animal remains (NISP: Number of identified specimens and %) from bulk samples from the kitchen and the refuse dump.

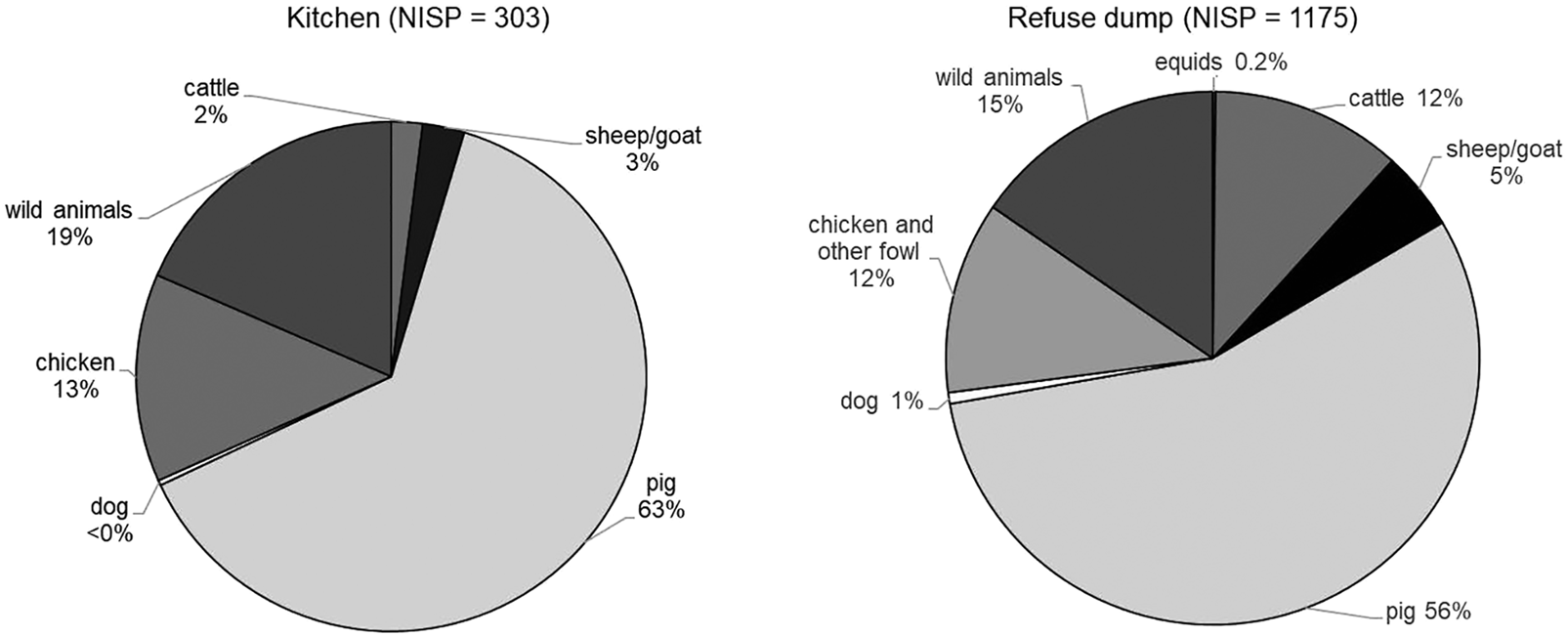

Fig. 7. Animal groups identified in bulk samples from the kitchen (left) and the refuse dump (right). Fish scales, eggshells and a reptile bone (n = 1, kitchen) are not included. (S. Häberle.)

Fig. 8. Phalanges of songbirds with various cut marks. (S. Häberle.)

Fewer remains (n = 869) were counted in the five samples from the refuse dump and a lower density (177 remains per liter) was observed. In total, 617 remains allowed a taxonomic identification. The bones were fragmented and rounded but showed no traces of burning. Twenty-three percent of the bones, mainly the tiny bone fragments from large mammals, but also some fish and bird remains, showed traces of digestion.Footnote 47 Furthermore, in the refuse dump, remains of birds (n = 88), as well as eggshells, are less frequent than in the kitchen. The few songbird bones are represented by articulation parts of long bone, vertebrae, or ribs but no foot bones. Even though there are fewer fish remains present than in the kitchen (n = 156), the species spectrum seems to be similar and includes mainly remains of perch and mackerel. The proportions of fish scale (62%) and head bones (4%) are similar to those in the kitchen, but there are fewer fin rays (12%) and more vertebrae (22%). Some shell fragments of land snails and oysters are present, too. The most frequent remains, however, are from small mammals, mainly murids (49%), most probably wood or yellow-necked mouse (Apodemus sp.) and house mouse (Mus musculus) (Fig. 7, right). All body parts and specimens from different age groups were identified. We observed pathologies, such as a healed bone fracture on a rib, and healed injuries on two foot bones. These pathologies, as well as the variety of age classes and the completeness of the skeletons, suggest that the rodents were most probably seen as pests, and hunted and disposed of on the refuse dump. Thus, mixed material of different origins, including kitchen waste, food remains, and fecal matter and pest carcasses, has been deposited in one place.

Archaeozoology: hand-collected animal remains

The hand-collected animal remains are in a good state of preservation. While in the kitchen 364 bones were collected, 1,359 remains were counted in the refuse dump (Table 5). Differences have been observed in the average weight of the remains: bones in the kitchen have an average weight of 5 g, those from the refuse dump, an average weight of 12 g. Furthermore, no bones with rodent gnawing marks and only a few bones with dog/pig gnawing marks (<2%) have been noticed in the kitchen. In the waste disposal area, a small proportion of rodent gnawing marks (<1%) but a higher proportion of marks from dog/pig have been observed (up to 12%). Cut and hack marks indicating the preparation of meat can be observed on 30% of the bones in the kitchen and 35% in the refuse dump.

Table 5. NISP (Number of identified specimens) and weight (n and %) of hand collected animal remains from the kitchen and the refuse dump.

In the kitchen and in the refuse dump, a diversity of species is present. In both features, pig remains (Sus domesticus) are dominant at more than 60%, followed by chicken (Gallus gallus dom.), with 12% in the kitchen and 11% in the waste disposal area. Besides chicken, goose (Anser sp.), duck (Anas sp.) and pigeon (Columba sp.) were also found, although it was often not possible to distinguish between the domesticated and the wild forms. Cattle (Bos taurus) and sheep/goat (Ovis aries/Capra hircus) are less frequent (Fig. 9). Particularly apparent is the high proportion of wild animals in both features (18% in the kitchen and 15% in the refuse dump), consisting mostly of hare (Lepus europaeus) and red deer (Cervus elaphus) but also of single finds from roe deer (Capreolus capreolus), wild boar (Sus scrofa), and even fallow deer (Cervus dama),Footnote 48 as well as birds like mallard (Anas platyrhynchos), partridge (Perdix perdix), and fieldfare (Turdus pilaris). Oyster shells were also identified. While domestic and wild animal remains can be considered food waste, this is unlikely to be the case for finds of dog (Canis familiaris), cat (Felis dom./sylvestris), and rat (Rattus sp.) from the refuse dump.

Fig. 9. Hand-collected animal bones: identified species and animal groups in the kitchen (left) and refuse dump (right). (S. Deschler-Erb/S. Häberle.)

The distribution of skeletal elements from pig shows comparable values in the kitchen and in the refuse dump. Foot bones are very frequent, while the larger limb bones have a normal distribution. Head and thorax elements are underrepresented. In contrast to the domestic animals, red and roe deer are represented by all body parts. As expected, and in contrast to the remains from the bulk samples, hand-collected bird bones are mainly represented by the larger limb bones, and foot bones are rare. Head bones from fowl are not frequent in either hand-collected or bulk-sample material (probably due to their high fragility). The question is therefore whether the heads had been removed before the birds came into the kitchen.

In both features, 70% of the pigs were slaughtered before or at their optimum slaughter age (about 2 years), when they produced the maximum amount of meat with the best quality. In addition, there were a few remains of very young individuals (neonate-infantile). More than half of the cattle remains stem from young individuals, again indicating a high meat quality, while the small number of sheep/goat bones stem mostly from adult individuals.

Reconstruction of kitchen activities, diet and social context

This interdisciplinary study of closely related domestic features (kitchen, anteroom, and refuse dump) in a well-defined spatial context provides an excellent case study of how a systematic and well-planned consideration of multiple features and different types of finds from the start of excavations up to the publication of the results produces rich and detailed insights. The results would probably have been quite different if the focus had been on only a single feature (e.g., the kitchen) or if not all disciplines had been involved. In this section, we will present the results of our interdisciplinary investigation and compare them with other studies. In doing so, we want to show that such investigations have a great potential for comparative studies in a wider (temporal and spatial) context and are an outstanding approach to exploiting a site's potential regarding cultural and historical information.

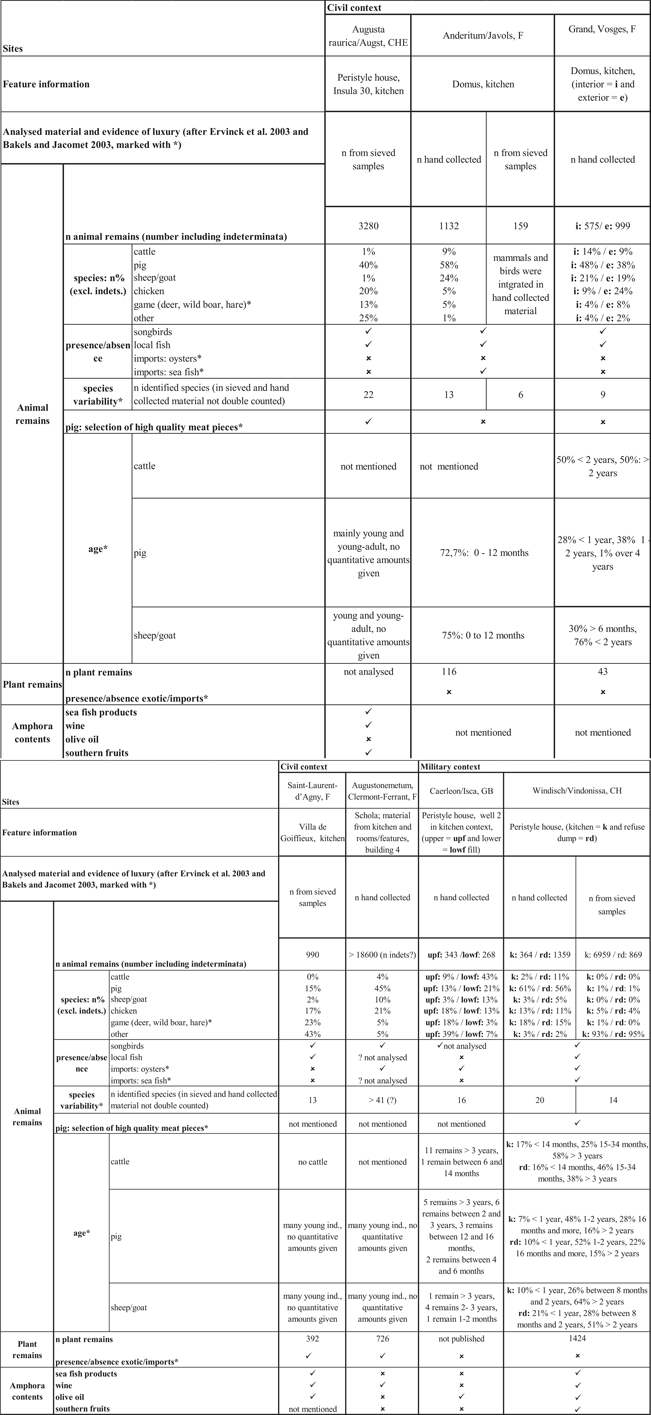

Our study of the peristyle house at the military camp of Vindonissa revealed numerous details about different kitchen activities there. Our results paint a vivid picture of food preparation, kitchen maintenance, and waste management at the site. Furthermore, the plant remains, the animal bones, and the amphorae allow us to reconstruct the ingredients used in cooking, their grade of quality, and the associated eating traditions, even if the archaeobiological data is somewhat biased in that some food components may not have been preserved.Footnote 49 A comparison of our archaeobiological results with those from other Mediterranean-style kitchens in the northwestern provinces will provide valuable insights on their social contexts and the supply situation of the peristyle house inhabitants (Table 6).

Table 6. Roman kitchen features, with a raised hearth and analyzed archaeobiological material. Listed and compared are summarized archaeozoological data and suggested luxury indicators according to Ervynck et al. Reference Ervynck, Van Neer, Hüster-Plogmann and Schibler2003, the presence/absence of plant remains and plant imports (indicator of luxury after Bakels and Jacomet Reference Bakels and Jacomet2003) and the absence/presence of amphora finds with imported goods. For dating and references, see Table 1.

Food processing, prepared dishes, and food storage

The L-shaped, raised hearth represents the central element in the kitchen for food preparation such as boiling, cooking, roasting, and maybe baking (Fig. 10). To ensure a long-lasting and even ember, people relied on the excellent burning properties of red beech wood,Footnote 50 which was available in the nearby surroundings of Vindonissa. Beech wood was also used in the domus kitchen of Javols/Anderitum or Grand (F).Footnote 51 The fire was lit directly on the brick work surface, as there are no openings on the sides of the hearth. Even if it has not been demonstrated for the kitchen in Vindonissa, it is also conceivable that charcoal was used.Footnote 52

Fig. 10. Reconstruction of the daily use of the kitchen from the peristyle house. (© Kantonsarchäologie Aargau/Digitale Archäologie Freiburg i. Br.)

Plant-based meals such as cereal or legume porridge, pearl barley, and groats (puls polenta, etc.) enriched with fruit, vegetables, and spices were prepared in the kitchen – these foods are traditional and some of the most common during Roman times.Footnote 53 Such dishes could have been prepared in coarse pots or bowls, which were the most commonly found vessels in the kitchen and the refuse dump.Footnote 54 The grinding bowl imported from Italy was probably used intensively (especially to grind herbs and spices), as shown by the scuffed bottom.Footnote 55 Additionally, cereals were used to make flour for flatbread or fermented bread. In Roman times, specific cereals were used or favored for different products;Footnote 56 for example, wheats are particularly suitable for bread-making, millets for porridges. The many charred amorphous objects (CAO) in the kitchen suggest the presence of both porridge and bread. Dehusking of the grain must have taken place elsewhere, as indicated by the absence of cereal chaff. Likewise, the absence of millstones indicates that the grinding of grain took place outside the kitchen. Finally, a bread oven was not part of the fixed kitchen equipment.Footnote 57 As bread was of great importance in the military camps (panis militaris),Footnote 58 it is likely that the inhabitants of the house acquired it from larger communal bread ovens, which are known for Vindonissa as well as for other legionary camps.Footnote 59

Meat certainly played an important role in the kitchen. It was prepared for slow-cooking soups or stews, for which larger pieces of meat were cut up with the butcher's knife. It seems that from pigs, selected cuts (ham, shoulder, knuckle, feetFootnote 60) were prepared. Of course, larger pieces of boneless meat are no longer traceable in the kitchen, as is the case at most archaeological sites.Footnote 61 Poultry and songbirds entered the kitchen as whole animals. It is probable that caged birds were also kept here for some time and were gutted and maybe also slaughtered in the anteroom, followed by further dissection (feet and heads cut off) in the kitchen. Prepared in this way, songbirds were perhaps used as stuffing for pies or for roasted suckling pigs as recommended in Apicius's recipes.Footnote 62 Whole freshwater fish were also cut up and prepared, with at least the inedible fin rays and scales removed. Roasted and grilled meat was presumably also prepared, but no equipment used for this, such as metal vessels, skewers, or grids, was recovered. Wooden vessels or utensils were also not present but were certainly used, as evidenced by finds in the Vindonissa waste mound, located near the camp.Footnote 63 Judging by the size of the hearth and the large quantity of vessels, a cooking team of several people was probably kept busy preparing the dishes for a large household.Footnote 64 The numerous amphora finds also indicate a high consumption of imported fish sauces, wine, and olive oil. Imported mackerel (salsamentum), oysters, and amphorae for preserved southern fruits were also present. The estimated annual consumption of 408 liters of olive oil was unusual for this time in the region north of the Alps and indicates a household of significantly more than 10 people.Footnote 65

The amphorae are some of the few indications of food storage. Other large storage vessels, such as dolia, are not found in the pottery inventory.Footnote 66 We do not know from the evidence available whether or not larger containers made of wood (e.g., wine barrels) or other perishable materials such as willow plants were also used as storage containers. Perhaps the ceramic pots, which were so numerous and of different dimensions, could also have served as storage vesselsFootnote 67 and may be a sign of a stable supply of fresh produce. However, from the archaeobiological and archaeological evidence in the kitchen and the presumed storage room (adjoining room, R3) it is not clear which food products were stored. There is no evidence of cereal stocks, bacon sides (recognizable from the high number of systematic rib bones of the same size),Footnote 68 smoked beef shoulders (recognizable from the perforated shoulder blades, which testify to hanging in the smokehouse),Footnote 69 or sausages, which were extremely popular in Roman times but are not recognizable in the archaeological record.Footnote 70

Waste management, cleaning, and maintenance

According to the microstratigraphy, a sequence of at least four loam floors and related occupation deposits was present in the adjoining room and possibly in the kitchen. The floors were renewed several times by the application of new loam coatings. A similar floor installation and loam floor renewal has previously been observed in the kitchen floor from Augusta Raurica, Insula 30.Footnote 71 These floors consisted partly of reused daub, which had been dumped to form beaten earth floors. Dirt, ashes, and charcoal accumulated, and remains of food preparation were carried from the kitchen into the anteroom.Footnote 72 In the kitchen itself, charred seeds and fruits, charcoal, and small bones likely fell onto the loam floor during food preparation and were trodden into it. However, the low average weight of the hand-collected animal bones shows that the floor was kept clean of large-scale rubbish and coarse dirt. Through the movement of working people or by sweeping the floor, the remains were distributed over a large area before being embedded. The predominance of animal bones versus charred plant remains at Vindonissa has also been observed in other Roman kitchen features.Footnote 73 Likely, the heavy use of the floor was the reason why the loam coatings had to be renewed several times.

Most of the larger kitchen waste and food leftovers were disposed of directly on the refuse dump next to the southern outer wall of the peristyle kitchen. Other waste such as fecal remains (indicated by mineralized plant remains and animal bones with traces of digestion) and mouse carcasses were also thrown on the dump. The high proportion of animal bones with gnawing marks indicates that dogs or other stray animals were disturbing the food leftovers in the rubbish.Footnote 74 Considering the duration of use of the peristyle building and the relatively small size of the waste pile (3 m2), it is assumed that the material in the dump represents only a short period of disposal before the building and the camp were abandoned. Additionally, it seems that a large part of the ceramic kitchen inventory was disposed of in one action shortly before the abandonment of the camp, as the departing troops did not want to take it with them.Footnote 75 In contrast, the more precious metal vessels, the grills, and the roasting spits were probably taken away, as they are missing from the kitchen inventory.Footnote 76

Most probably, the waste was regularly transported away during the period of use of the kitchen.Footnote 77 We know from other archaeological sites and written sources that waste was transported outside of Roman settlements,Footnote 78 as is the case for the legionary camp Vindonissa (Fig. 11).Footnote 79 A wide variety of waste (pottery, mixed building rubble, bones, and also other organic material preserved due to the waterlogged conditionsFootnote 80) was dumped on the debris and waste mound (approximately 50,000 m3) found immediately north of the camp.Footnote 81

Fig. 11. Reconstruction of the waste mound in front of the northern gate of the legionary camp of Vindonissa. (© Kantonsarchäologie Aargau/Atelier Bunter Hund Zürich.)

Food components in Mediterranean-style kitchens: indicators of luxury

Obviously, most Mediterranean-style kitchen features from military and civilian contexts in the northwestern provinces can be assigned to the upper class, based on their archaeological features and finds, but detailed information about dietary habits and luxury ingredients depends on the additional availability of archaeobiological data. Many studies have dealt with the definition and recognition of “luxury food” in archaeobiological material from provincial Roman contexts in order to classify social status. In summary, they propose quality, rarity, and variety as important indicators.Footnote 82

On the basis of these indicators, we compared the plant- and animal-based food components of the Vindonissa kitchen and refuse dump with Mediterranean-style kitchens (Table 6) and a few other features where archaeobiological studies were undertaken. When considering the comparative data, it is important to bear in mind that the kitchen finds stem from different contexts and different regions and cover a period of around 400 years. Additionally, different methodological approaches were used, and fully quantified archaeobological data are not always published. Bulk samples for plant and microfaunal remains are not always taken, and different mesh sizes are used. The total number of studied remains is also very variable, which in turn could have an effect on the detection of rare species. Some studies use the archaeobiological remains not only from the kitchen but also from kitchen-related features, and some of them do not discuss the amphorae contents in detail. However, we have attempted to present the differently generated results as conclusively as possible in order to better classify our remains in terms of quality and to draw conclusions about social context.

Plant-based food components

Archaeobotanically investigated sites with clearly identified cooking installations from the Roman period are rare in Switzerland. So far, three have been investigated, namely a hearth from Insula 1, Room B6Footnote 83 and an oven and a hearth from Insula 23 at Augusta Raurica,Footnote 84 as well as a kitchen floor from the Villa Worb-Sunnhalde.Footnote 85 The state of knowledge regarding plant macroremains in Roman kitchens is therefore still very low. In France there is a little more information, thanks to a Table Ronde organized in 2011 and dedicated to this topic.Footnote 86 As far as the plant remains are concerned, taphonomy and preservation had a great influence on the taxa represented in the Vindonissa kitchen. Nevertheless, cereals (barley, broomcorn millet, naked wheat, and rye) and pulses (lentil and broad bean) were among the staple foods prepared in the kitchen, as has been established in other parts of the legionary camp of Vindonissa and other legionary camps in the provinces.Footnote 87 Fruits (fig, cherry, grape), nuts (walnut), and spices (dill, coriander) were also among the ingredients represented. The archaeobotanical results from the Vindonissa kitchen are consistent with the general picture known from previously investigated cooking installations. In general, only very few charred seeds and fruits are attested, as observed in the systematically sampled kitchen floor of Grand (F)Footnote 88 and in the kitchens of the domus from Anderitum/Javols,Footnote 89 in the Villa de Goiffieux,Footnote 90 in the schola kitchen of Augustonemetum/Clermont-FerrandFootnote 91 (all in Table 6), in the recessed oven from the villa de la Lesse in Sauvian (F),Footnote 92 and in the fireplace from Insula 1 in Augusta Raurica.Footnote 93 Charred amorphous objects (i.e., fragments of fruits or processed food such as porridge or bread), on the contrary, are observed very frequently. In the schola kitchen at Augustonemetum, very large quantities of CAO were found that could be identified as porridge from barley and millet.Footnote 94 In GrandFootnote 95 and Worb-Sunnhalde (CH),Footnote 96 the majority of the remains also came from charred processed food. Furthermore, in the Villa de la Lesse in Sauvian,Footnote 97 it has been observed that the plant spectrum in the kitchens is less rich than those found in other areas of the site. This also applies for the Vindonissa kitchen: a considerable variety of fruits and spices was attested in the refuse dump, but in the kitchen mainly cereals and pulses were identified.

Food plants classified as luxury foods, such as rice, black pepper, pistachio, almond, pine kernel, date, pomegranate, and olive,Footnote 98 were not recovered from the Vindonissa kitchen. All are exotic plants that cannot grow locally. These plants are only present in the early phase of Vindonissa, between 20 BCE and 15 CE. In the Vindonissa kitchen, however, a wide range of food plants introduced during the Roman period and possibly cultivated locally has been documented (e.g., apple/pear, fig, cherry, grape, walnut, dill, coriander), similar to other areas of the legionary camp and at most of the sites used for comparison. It is difficult to judge if these newly cultivated plants can be called luxuries, although their exclusivity was certainly related to the supply chains and demand at the time and varied depending on the region. The archaeobotanical finds from the stone building phases of Vindonissa fit into the general picture known for Roman Switzerland: the importation of exotic food plants occurred mainly in the earliest phase of Roman occupation and is often related to military occupations; with the beginning of the Roman period, a whole range of new food plants is introduced, which become more frequent towards the end of the 1st c., indicating local cultivation from then onwards.Footnote 99

Animal-based food components

Besides the criteria of rarity (e.g., imports) and variety, there are important quality criteria which can identify animal remains as luxury foods. They are the selection of quality meat cuts, products derived from young animals, and products subject to restrictive rights or privileges (e.g., game) (Table 6).Footnote 100 In summary, the comparison between the studied kitchens and the kitchen at Vindonissa revealed differences, probably caused by milieu (civil vs. military), dietary preference, and the regional food supply chain, but also related to the use of different methodological approaches in the archaeozoological analysis (e.g., sample sizes, hand-collected remains vs. remains from bulk samples). However, in Vindonissa all previously identified indicators of luxury are present. They include the large species spectrum with young individuals, the evidence of selected meat cuts from pig, the high proportion of large game, and the high quantity of imported goods. Our comparison shows that in each of the other kitchens, at least one indicator seems to be missing. The criteria of variety and rarity seem to be somewhat stronger in the cuisine of Vindonissa than at the other sites.Footnote 101 In all kitchens, pork was probably most commonly processed. Furthermore, in most of the kitchens high proportions of chicken but fewer remains of cattle and sheep/goat were observed. A deviation from this composition is observed in the tribune's kitchen-context well at camp Caerleon. In the lower fill of the well, which is assigned to the construction phase, a high proportion of cattle were noticed. In the upper fill of the well, however, which is assigned to the occupation phase, the composition is more similar to the other kitchens, even though there are fewer pig bones. This part of the fill particularly stands out due to the presence of several crane bones (Grus sp.) and a high quantity of fowl remains.Footnote 102 In Anderitum, again a different pattern could be discerned. In this kitchen, the lowest proportion of chicken but the highest proportions of sheep and goats can be found. In the kitchen at the Villa de Goiffieux, the many small bird remains reduce the proportion of domesticated animals.

Further differences can be observed for wild birds, fish, and imported food. Songbirds, as well as local fish species, imported oysters, and mackerels, appear together and in high proportions in the kitchen of Vindonissa, but not in the other kitchens. However, in Augst Insula 30, Javols/Anderitum, and the Villa de Goiffieux,Footnote 103 high proportions of songbirds were present, especially the remains of feet.Footnote 104 Numerous remains of unstudied bird bones were also mentioned for the kitchen of the tribune's house at Caerleon.Footnote 105 When fish remains are present in the studied kitchens, they mainly represent local freshwater fish, but with a lower species diversity than at Vindonissa. Mackerel is only present at Vindonissa and Anderitum/Javols; oyster shells at Vindonissa, Caerleon, and Augustonemetum. From this we can infer that species diversity is not only related to sample strategies, as some of the small animal remains were recovered in kitchens where bulk sampling (of the kind seen at, e.g., Augustonemetum, Villa de Goiffieux, and Caerleon) was not undertaken. In Vindonissa, a high species variety is noted (20 species) even without the inclusion of the species from the sieved bulk samples (14 species). Only at Augostonemetum is the species diversity higher (>41(?)Footnote 106 species) due to 19 identified (domestic and wild) bird species found in the hand-collected material.Footnote 107

In summary, the zoological remains from the Vindonissa kitchen and refuse dump include large amounts of pig, poultry, songbirds, freshwater fish, and game, as well as imported mackerel and oysters, and suggest a diet of high quality and variability, as well as a Mediterranean background to the prepared dishes. The Mediterranean influence is backed up by the large quantity of imported fish sauce amphorae (with an estimated content of 792 liters), suggesting consumption of about 0.4 liters a day, a large quantity by provincial Roman standards.Footnote 108

Regarding the selection of quality meat cuts and products of young animals, information can also be provided for most of the kitchens in this comparison, especially for pork. The quality of pork meat in the Vindonissa features, as from most of the other studied kitchens, was good. Meat was mainly selected from animals of optimal slaughter age, but piglets, popular as delicacies in Roman times, were also served.Footnote 109 It seems that in the studied kitchens, the example followed was that of Pliny, who noted: “No other animal [than pig] is better suited for feasting.”Footnote 110 However, a selection of high-quality meat pieces from pig (ham, shoulder, knuckle, feet) was observed only in Vindonissa and Augusta Raurica. Besides young pig, young sheep/goat were also found in most of the studied kitchens. The low number of cattle remains cannot conclusively be evaluated, but it seems that the meat from adult animals has been prepared (cf. Grand, Caerleon and Vindonissa.)

Finally, products subject to restrictive rights or privileges are mainly represented by the high proportion of big game in the Vindonissa kitchen and refuse dump. Most probably, hunting wild animals, especially large game, was an activity of those who lived in the house. In contrast to hare hunting, large game hunting seems to have been a typical privilege for high-ranking military personnel.Footnote 111 Interestingly, the same proportion of large game remains was recorded in the military camp at Caerleon (upper fill), while the high proportion of game recorded at the villa of Goiffieux and Augusta Raurica Insula 30 consists exclusively of hare. In the other kitchens, the values of game are below 10%.

Living comfort and luxury food: privileges of the upper ranks

The interdisciplinary study of the peristyle house kitchen at the camp of Vindonissa points towards both the high social status and the Mediterranean lifestyle of the residents. The prominent location in the immediate vicinity of the central principia as well as the Mediterranean-type construction of this large building and its furnishings indicates wealthy inhabitants.Footnote 112 The large size and equipment of the kitchen, as well as the large number of cooking vessels and amphorae in the refuse dump, also point in this direction and indicate food preparation by servants for a household of many people.Footnote 113

The archaeobiological remains reflect the high quality of the meals prepared and indicate a Mediterranean cooking style, even though exotic imports are not directly represented among the archaeobotanical finds. In this case, this absence should not be seen as an absence of luxury. What is considered a luxury food and thus an indicator of an affluent lifestyle also seems to change during the course of the Roman period. Earlier on, more plants had to be imported to meet the standards of Mediterranean cuisine, and only gradually did locally grown plants of non-native species become available. It is possible that in the kitchen of Vindonissa, imports were not the most important indicator of luxury and wealth: wealth is instead better reflected by the methods of preparation, and the stable supply of introduced and cultivated plants such as fig, apple, pear, grape, and walnut. Furthermore, the purchase of processed foods such as bread and flour could also be a sign of wealth, as assumed for the kitchen of Grand.Footnote 114 In the archaeozoological material of the Vindonissa kitchen and refuse dump, many obvious indicators of luxury testify to the high culinary demands and Mediterranean eating habits of the inhabitants. The animal-based foods that were consumed also reflect the well-organized provisioning of the military. It seems very likely that within the camp of Vindonissa a large variety of luxurious meat dishes and especially the consumption of large game were related to a high military rank, the financial power that came with it, and the probable Roman origin of the inhabitants. In the case of the peristyle house, it was most probably a centurion of the 1st cohort (primi ordines) who lived in this house with his family and servants.Footnote 115 However, the archaeozoological database of military contexts is still small, and further differences with comparable civil kitchens are hard to interpret.

In the present state of our knowledge, it can be suggested that using locally produced, high-quality food and traditional Roman ingredients was probably a way to generate a Roman elite consciousness and to strengthen its members’ social positionFootnote 116 – be it in the upper civil society or in the upper military milieu. This may well be true for the provinces as well as for the motherland.

Funding

This research was partially funded by the Kantonsarchäologie Aargau and Department of Environmental Science, University of Basel, Switzerland.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Kantonsarchäologie Aargau and University of Basel for funding this study. We thank the previous project leaders Stephan Wyss and Stefan Reuter for their valuable work. Special thanks go to Dr. Lizzie Wright for copyediting the text and to the three reviewers for their valuable comments and suggestions that have improved and clarified the manuscript.

Competing interests

The author(s) declare none