Introduction

Composing still remains relatively marginal in the general music educational practices of many countries. This is in spite of several attempts already made decades ago to point out the educational significance of composing in general (e.g. Paynter & Aston, Reference PAYNTER and ASTON1970), as well as more recent arguments emphasising the importance of giving arenas for students' creativity (e.g. John-Steiner, Reference JOHN-STEINER2000; Barrett, Reference BARRETT2006; MacDonald et al., Reference MACDONALD, BYRNE and CARLTON2006) and the development of agency (e.g. Walduck, Reference WALDUCK, Odam and Bannan2005; St. John, Reference JOHN2006; Mantie, Reference MANTIE2008). Teachers may lack confidence in teaching composing (e.g. Winters, Reference WINTERS2012), often due to the rather common view of composing as the solo endeavour of a ‘lone genius’ producing authentic musical ideas, and embarked upon only after lengthy formal studies. This individualistic view of musical expertise, reserved for the chosen few, is still widespread among professional educational institutions within Western classical music, and has prevented the profession from fully recognising the ever more evident strengths of collaborative composing, particularly in educational settings. According to a recent report in Finland, for instance, nearly half of the students (47%) in lower secondary schools stated that they had never experienced making their own music in school even though composing has been included in the Finnish National Framework for Music Curriculum for several decades (Juntunen, Reference JUNTUNEN, Laitinen, Hilmola and Juntunen2011).

As suggested by recent studies, collaborative composing may function as a way to ‘generate more, and a greater variety of musical ideas’ (Faulkner, Reference FAULKNER2003, p. 115), and provide ‘opportunities for increased development across a broad spectrum of musical intelligence’ (Brown & Dillon Reference BROWN, DILLON, Finney and Burnard2007, p. 97), as well as supporting students' deeper self-understanding (Barrett, Reference BARRETT2006), mutual appreciation (Rusinek, Reference RUSINEK2007) and the growth of their ‘cultural knowledge and confidence’ (Miell, Reference MIELL2006, p. 147). Moreover, collaborative composing offers potential for developing more democratic learning environments (Allsup, Reference ALLSUP2003, Reference ALLSUP2011). Despite this growing awareness of composing collaboratively, music teacher graduates are reported to often have only few, if any, personal experiences of group composing when entering school (e.g. Faulkner, Reference FAULKNER2003), and may find themselves perplexed in the midst of the complex and diverse processes of teaching musical composing to groups of students (Fautley, Reference FAUTLEY2005; Clennon, Reference CLENNON2009; Sætre, Reference SÆTRE2011).

While there are only few experiences and pedagogical models of group composing within institutions of higher music education (e.g. Allsup Reference ALLSUP2011), user-generated online communities are increasingly providing new possibilities for a wide range of music makers to experience and learn composing through an open-ended collaboration (e.g. Salavuo, Reference SALAVUO2006; Partti, Reference PARTTI2009; Partti & Karlsen, Reference PARTTI and KARLSEN2010). In this article, we will explore one such community, namely the international operabyyou.com, initiated in May 2010 by the Savonlinna Opera Festival in Finland, with a public performance at the festival of a collaboratively composed opera named ‘Free Will’ scheduled for July 2012. The Opera by You project not only exemplifies an emerging cultural shift from an individualistic one to that of a collaborative understanding of composing, but it also demonstrates a blurring of the boundaries between formally educated experts and informally trained amateurs within the same community as it provides online access for anyone, independent of their educational background, stylistic preferences, or geographical location, to contribute to the opera – to the writing of the libretto, composing of the music as well as to the designing of the sets and costumes.

By advancing heuristically the theories of sociocultural learning (e.g. Bruner, Reference BRUNER1996) in general, and of so-called communities of practice (Lave & Wenger, Reference LAVE and WENGER1991; Wenger, Reference WENGER1998; Wenger et al., Reference WENGER, MCDERMOTT and SNYDER2002, Reference WENGER, WHITE and SMITH2009; Lea, Reference LEA, Barton and Tusting2005) and communities of musical practice (e.g. Barrett, Reference BARRETT, Miell, MacDonald and Hargreaves2005) in particular, we will explore collaborative composing in operabyyou.com (hereafter abbreviated as OBY) from the perspective of learning; learning understood as a thoroughly social endeavour, having a dynamic relationship to one's construction of identity and experience of meaning. We will employ the approach of a qualitative instrumental case study (e.g. Stake, Reference STAKE1995) to investigate how OBY informs, though may not yet model, collaborative composing in music education, and ask how is the learning and ownership of musical meaning enhanced or constrained in the OBY online community. By collaborative composing, we refer to composing activities leading to a joint product that has been created by more than one person providing a musical contribution(s) to the process and/or to the end product of the collaboration. Unlike other music education researchers who have been interested in musical learning outside of formal education (see, for instance, Green, Reference GREEN2001; Söderman & Folkestad, Reference SÖDERMAN and FOLKESTAD2004; Salavuo, Reference SALAVUO2006; Karlsen & Brändström, Reference KARLSEN and BRÄNDSTRÖM2008; Waldron, Reference WALDRON2009), our approach to the Opera by You project is critical. Hence, this study takes a critical stance toward musical practices outside institutional music education to envision educationally grounded collaborative composing practices beyond the case of the OBY community.

The case of operabyyou.com: data collection and analysis

The OBY online community operates on a web platform that facilitates communication between the members of the community in several ways: the members may create their own profile page, initiate and participate in discussions or post comments on each others’ contributions related to the overall composing task. As such, the research data for this study consists of the OBY member's individual online profiles, the composing task related online discussions collected during the first year of the OBY community from May 2010 until June 2011, and computer-assisted interviewsFootnote 1. Besides the online profiles, discussions and the email interviews, the Festival organisation provided demographic statistics related to the participants of the emerging online community. To ensure the successful completion of the opera within the given time frame, the Festival organisation appointed six professionals within the field of dramatic art – referred to as operatives by the Festival Organisation – including a production leader, librettist, producer and composer, to lead the work in the OBY community. Having begun in mid-September 2010, composition had been set to proceed under the leadership of the musical operative, a Finnish professional composer, Markus, whose role is to guide the OBY participants who engage, in any capacity, in the creation of the music for the opera. In short, Markus’ duties are to design, present and explain the musical assignments for the community to get on with. It had also been decided by the Festival Organisation that Markus will combine all the notated musical passages composed by the OBY members and merge them into one score.

Opera by You is the first opera production operating on a platform called WreckamovieFootnote 2 that was initially launched to facilitate online collaborative film making. Consequently, online discussions on OBY have appeared in three separate areas that reflect the division of labour of the Wreckamovie platform's structure: (1) TASKS, a notice board on which the musical operative could announce new Tasks for the members to work on, and where the members could upload their own contributions, i.e. Shots, as well as comment on each others’ Shots; (2) BLOG, a forum for the musical operative to start Threads, which include discussions about tools, practices and other more general themes related to the composing of the opera; (3) FAQ, a discussion board for member or operative initiated questions and/or comments about the production, referred to as Shots. Every discussion about the composing of the music was collected and analysed during the data collection period. There were 7 Tasks (with 59 Shots and 72 Comments) on the TASKS area, 9 Threads (with 12 Comments) on the BLOG area, and 10 Shots (with 89 Comments) on the FAQ area; altogether 259 online messages.

The structured, computer-assisted interviews, carried out with five voluntary OBY composers serve as an additional source of case study information (see, for instance, Yin, Reference YIN1994). The choice of interviewees was based on the list provided by the Festival organisation of ‘the most active composers in OBY’ (email communication in 21 March 2011). According to our own calculation, there were altogether approximately 10 to 15 members involved with composing the music in the OBY community during the period of the data gathering. We approached the seven ‘most active’ composers through their OBY profile by sending them a message in which we explained the purpose of the study and provided a list of questions. Five of them answered the questions. Each of the interviewees were asked the same questions enquiring about the composers’ reasons for and experiences of participating in the OBY project as well as about their musical background and possible previous experiences of collaborative composing. While an email interview may fall short of providing ‘rich and detailed descriptions’, the interviews proved to be a practical and non-threatening way to address aspects in the lives of geographically distant people (Kvale & Brinkmann, Reference KVALE and BRINKMANN2009, p. 149).

Rather than providing a thick description of the cultural system of OBY, our instrumental interest in analysing the initial stages of the collaborative composing project was to reflect on the conditions for learning in OBY and the transformation of a group of people, from various parts of the world, and provided with different levels of musical expertise, into a collaboratively composing community. Through exploring the processes of negotiation of meaning taking place in the early stages of OBY, we aim to ‘draw [our] own conclusions’ (Stake, Reference STAKE1995, p. 9) beyond the case. The verbal negotiation, descriptions, interviews and other accounts appearing in the research material were analysed by using a ‘theoretical reading analysis’, as proposed by Kvale and Brinkmann (Reference KVALE and BRINKMANN2009; see also Miles & Huberman, Reference MILES and HUBERMAN1994, pp. 245–246). The analysis proceeded through carefully reading and re-reading the research material from the aforementioned positions and by reflecting ‘theoretically on specific themes of interest’ (p. 236) to make interpretations based on the theories. In this type of analytical approach, the researcher is considered to be a ‘craftsman’ (p. 234), whose creativity (p. 239) and ‘extensive and theoretical knowledge of the subject matter’ (p. 236) is of crucial importance ‘in putting forth new interpretations and rigorousness in testing the interpretations’ (p. 239). To ensure that the theoretical reading would not ‘block seeing new, previously not recognized, aspects of the phenomena being investigated’ (p. 239), the research material was also examined through narrative analysis, where we constructed ‘coherent stories’ (Kvale, Reference KVALE1996, p. 201) of successions of happenings on OBY by synthesising and temporally organising them into new episodes.Footnote 3 The aim of the process of narrative configuration (Polkinghorne, Reference POLKINGHORNE, Hatch and Wisniewski1995) was to obtain an understanding of the happenings ‘from the perspective of their contribution and influence on a specific outcome’ (p. 5).

Theoretical points of departure: ‘community of practice’ as a heuristic lens

As a starting point, we agree with Etienne Wenger (Reference WENGER1998) that whenever we come together to do things and collaborate, we engage in various activities utilising all sorts of techniques and instruments, yet, it is not these activities, techniques, or tools in themselves that give meaning to our experiences. Rather, we are actively producing meanings ‘that extend, redirect, dismiss, reinterpret, modify or confirm – in a word, negotiate anew – the histories of meanings of which they are part’ (pp. 52–53). This production of meanings surrounds and penetrates learning, and constitutes a process that Wenger refers to as negotiation of meaning. Negotiation of meaning is shaped by our present and previous experiences, interactions and negotiations of meaning in a variety of social communities, but it also shapes the situation in which the negotiation takes place, and hence has an impact on every participant involved. In short, through negotiation of meaning, one is able to experience the activities and one's engagement in them as meaningful – or meaningless.

According to Wenger, negotiation of meaning is an inherent part of such communities that essentially revolve around learning, regardless of whether the community is set up explicitly for learning purposes or not (Lave & Wenger, Reference LAVE and WENGER1991; Wenger, Reference WENGER1998; Wenger et al., Reference WENGER, MCDERMOTT and SNYDER2002, Reference WENGER, WHITE and SMITH2009, Reference WENGER, TRAYNER and DE LAAT2011). As a distinction from any kind of temporary social setup, communities of practice are understood to be built on the mutual engagement of the participants who pursue a joint enterprise through ongoing interaction and by developing a variety of shared resources, ‘produced or adopted’ over time, having become part of the practice of the community (Wenger, Reference WENGER1998, p. 83). The members of a community of practice negotiate their experiences, interpretations and understandings while partaking in the activities and interacting with others in the community. Therefore, a community of practice is a place for ‘the formation of identities and social configurations’ (p. 133), the development of practices, and ‘joint learning’ (p. 96), in which learning takes place through participation in the shared activities of the community of practice. As Wenger writes, learning is understood as a thoroughly social process rather than ‘a special category of activity or membership’ (p. 95) or simply a mental acquisition process of an individual. Accordingly, learning is always also an experience of identity, as it changes ‘our ability to engage in practice, the understanding of why we engage in it, and the resources we have at our disposal to do so’ (pp. 95–96). As a heuristic, the concept of a community of practice provides a lens through which to investigate not only how a community may enhance learning through participation, but also, as Lea (Reference LEA, Barton and Tusting2005) suggests, the ways in which learning is constrained and how ‘certain ways of making meaning are privileged to the exclusion of others’ (p. 188).

OBY as a task-based community

Since the beginning of the community, the demanding objective of producing the final public performance of the opera within a relatively short period of time has been at the centre of activities in OBY. Therefore, OBY could be compared to task-based learning communities, using Riel and Polin's (Reference RIEL, POLIN, Barab, Kling and Gray2004) terminology, with its principle interest in the completion of a task; the production and completion of an artefact. The activities of a task-based community are strictly defined by its stated goal, yet, the participants of such a community may, as pointed out by Riel and Polin, ‘experience a strong sense of identification with their partners, the task, and the organization that supports them’ (p. 20). In their online profiles and interviews, OBY participants indicated indeed that being part of the creation of a ‘real’ opera was highly motivating. The reasons for joining OBY varied from curiosity about the novel project to the expectancy of finding a platform for one's own music.

I didn't initially intend to compose music [for the “Free Will” opera], as I do not, in any way, regard myself to be even close to being ready to compose an opera – I do not have skills of a professional composer, but apparently I am able to draft music to the extent that a professional such as Markus can use my sketches as material. After realising that I might end up hearing the music composed by me on the stage of Savonlinna for real, finding and maintaining the motivation has not been difficult. (Member A, interview material)

I enjoy writing music, and while I have been involved with some other projects, I have never written the music for an opera. What did I hope to gain? Well, I guess you could say the most important thing in the world: enjoyment, and the ability for other people to hear my music. (Member D, interview material)

Many of the participants also viewed OBY as ideal in allowing its members to be involved in a community where it would be possible to accomplish something greater than one could ever do by oneself, as well as to learn more about composing. As some of the composers explained:

[I a]lways wanted to contribute to writing an opera. [I have] just finished a musical together with a couple of friends and want to continue learning. (Online profile 1)

– it's so very exciting to be working at a high level with people from all over the world. It really gives you the sense of participating to something great! (Member B, interview material)

I compose music occasionally – and I want to see how this project became real on a stage to encourage me to follow composing. (Online profile 2)

I think it is a nice experience to collaborate with many people from all around the world in creating a great art work (Member E, interview material)

OBY hence has provided a unique opportunity to attend the production of an opera, or, in Meyerson's (Reference MEYERSON1948) and later Bruner's (Reference BRUNER1996) terminology, an oeuvre that exceeds any individual capacities; that can fulfil an existence of its own and ‘give pride, identity, and a sense of continuity to those who participate, however obliquely, in their making’ (Bruner, Reference BRUNER1996, p. 22). Importantly, the OBY participants share a love of opera and a willingness to keep the art form thriving:

I love opera, and it is the responsibility of opera lovers around the world to keep reinventing the genre, so we can gain more and more fans of opera of all ages and national backgrounds! We must keep opera alive! (Online profile 3)

[My motivation to participate is:] The experience of collaborating with others around one of my greatest passions . . . OPERA! (Online profile 4)

As with many other online music communities, becoming a member of OBY is made easy: all one has to do is to sign up by entering a name, email address and password onto an electronic form. Within a year after the launch of the OBY online community, approximately 400 individuals between 30 to 35 years (of which female ratio approximately 40%) were collaborating in the project as a whole. Geographically, the participants have come from 43 countries, and approximately 20 of them are involved in the composing of the music. In the interviews and online profiles, the composers define themselves anywhere from being beginning amateur musicians, self-taught musicians with prolonged histories of various music-making, to professional musicians with formal education. Unlike online music communities such as mikseri.net where people may contribute whatever they wish (e.g. Partti Reference PARTTI2009), in the OBY community the participants compose music for particular parts of the score at a given time, as commissioned by the musical operative. Although the assignments are designed and given by the musical operative, there are, however, no directives or limitations in terms of the musical genre or style. After the members have submitted their notated contributions – ranging from one bar to lengthy passages – the musical operative merges the musical snippets into the piano score, and later into the final orchestra score, thus aiming to weave the spectrum of various styles into a coherent piece of art. Moreover, the musical operative does not merely create a musical collage according to his own taste, but strives to democratically utilise all the contributions of the members.

As a consequence of this division of labour, effectiveness in promptly completing the task appears to be the strength of the OBY community. ‘Theoretical reading analysis’ (Kvale & Brinkmann, Reference KVALE and BRINKMANN2009) enables us, however, to view why this might be considered educationally limited. In the following, we will further examine learning and identity work in OBY through a sociocultural perspective.

The dual process of identity construction

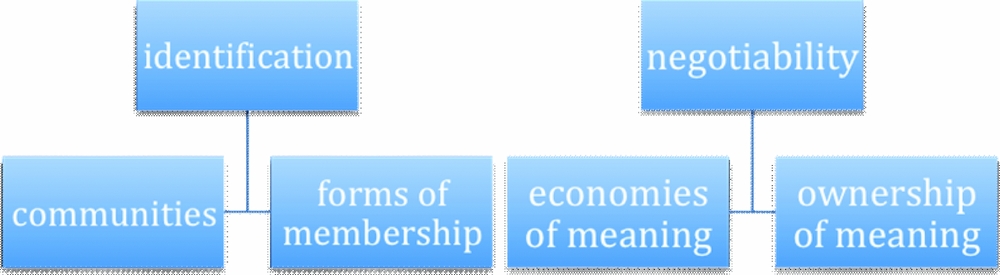

In the same way that meaning does not come into being by itself but is constructed and reconstructed through negotiation, identity is here understood to exist ‘not as an object in and of itself – but in the constant work of negotiation the self’ (Wenger, Reference WENGER1998, p. 151). By negotiating the meanings of their experiences of membership in the OBY community, the participants are also building their identities as opera composers. This identity work is considered to be an interplay between two distinct, but reciprocally accomplishing and inseparable elements, namely identification and negotiability. To open up this dual process of identity construction, Wenger uses the metaphor of economy of meaning to highlight ‘the social production and adoption of meaning, and thus the possibility of uneven negotiability and contested ownership among participants’ of communities (p. 210). Communities and economies of meaning draw attention to distinct aspects of social configurations, and hence ‘require and reflect different kinds of work of the self’ (p. 210). As illustrated in Figure 1, the former links closely to the work of identification and the participants’ ‘investment in various forms of belonging’, while the latter reflects the work of negotiability, referring to the participants’ ‘ability to negotiate the meanings that matter in those contexts’ (p. 188).

Fig. 1 Dual process of identity construction (the figure is based on Wenger's (Reference WENGER1998) diagram on p. 192, and p. 198)

Identification

The reasons the OBY composers gave in the interviews for their participation reflect the power of imagination as a source of identification with specific large groups of people, such as that of ‘opera composers’.

– working on a real Opera was really something I had been dreaming of. It was mainly this which inspired me, along with the fact that I appreciate much of Finland's musical reality. When I read about the project in a newspaper, I immediately thought: this is the chance to prove my value, and to see if I can be appreciated for my work and my knowledge. (Member B, interview material)

According to Wenger (Reference WENGER1998, p. 195), ‘imagination can yield a sense of affinity, and thus an identity of participation’. This imagined sense of affinity inspires the participants of OBY to invest their time and effort in composing, and engaging in the project was consequently seen to offer significant existential value:

– my main purpose was to give my (musical) contribution to something that would hopefully survive in time, and live beyond me – participating in the work is like putting a little piece of my soul into something that will potentially live forever. (Member B, interview material)

[My motivation of participation is t]o be a part of something unique. Showing the world of creativity to my daughter (now age 7) and letting her be a part of it too. Proving to myself that there is life after cancer. (Online profile 4)

This perception of the value of the envisioned ‘joint product’ – the collective oeuvre (Bruner, Reference BRUNER1996, p. 76) – forms starting points for the OBY community to appear. Imagination, for its composers, is like ‘looking at an apple seed and seeing a tree’ (Wenger, Reference WENGER1998, p. 176): an ability to envision the opera performance and their own place in the canon of opera music, while participating in the slow and often arduous crafting of composing. For the participating composers, identification hence provided material for defining their identities as opera composers through their engagement in the activities and social interactions in OBY.

Negotiability

According to Wenger, identification is, however, only one aspect of social configurations. The other aspect, negotiability, enables the composers to use the material provided by identification to assert their identities ‘as productive of meaning’ (Wenger, Reference WENGER1998, p. 208). This takes place by negotiating what it means, or how to be an opera composer within the context of OBY. The participants’ pursuit of acquiring ‘control over the meanings’ (p. 188) in which they had invested is exemplified in an online discussion that took place at the beginning of the composing work, and was initiated by the participants themselves.

I would like [to] ask the operatives if they have formulated any ideas about the process of collaborative composing? Since the days of Beethoven, composers have been seen as torch bearers of heroic individualism. It would be quite something if this [OBY] could be made to work as a truly collaborative effort. I don't think it would be very good if we end up in a situation where everyone is in parallel composing his/her own thing in the loneliness of his/her study. (TASKS’ commentator 1 in 27 September 2010)

The discussion continued with the writer considering some practical ways to organise the composing work in a way that would ensure both the coherence of the final score and the collaborative nature of its creation. Another OBY composer concurred, and proposed that the community should have ‘a pool of musical ideas that can be shared by everyone and can inspire others, giving them the opportunity to evolve, as melodies or arrangements’ (‘TASKS’ commentator 2, 27 September 2010). The suggested tool would have been similar to ones used in software development to enable participants to share and organise any snippet created by any member of the community: ‘Everyone could then listen to the different versions of scores, choose the one s/he likes the most and contribute to its development’ (‘TASKS’ commentator 2, 27 September 2010).

As the composing of the opera continued throughout the following months, it became clear that suggestions for an open source ‘pool of musical ideas’ would not come to pass. Instead, the musical operative would make all the final choices between various musical suggestions, and merge the extracts into one score. This lack of admission to the process of assembling the musical whole led to discussions about ways to ‘cut and paste’ different snippets. One member voiced his puzzlement at finding a snippet by another composer placed in the middle of his own fragment. In his opinion, this ‘breaks the structure of the original fragment and therefore loses its coherence’ (‘FAQ’ commentator 1 in 21 January 2011). Other composers were quick to bring about reconciliation instead of continuing to defend their ‘own’ snippets. They reassured that ‘the beauty of the music is in the right balance between predictability and surprise’, and that ‘the fragmentation’ could, in fact, be considered as ‘a part of the style of this work’ (‘FAQ’ commentator 2, 21 January 2011).

Although negotiation exhibits the OBY composers’ concern for collaboration and learning, interestingly, the urgency to complete the task resulted in a reluctance to get involved in a prolonged negotiation of meaning. As stated earlier, identification and negotiability can each result in participation as well as non-participation (Wenger, Reference WENGER1998, p. 189), and identification ‘can be both positive and negative’ (p. 191) as it always includes what one prides oneself on being and what one scorns. Furthermore, as a socially organised experience, identification might give rise to non-participation as we are labelled not only by ourselves but also by others, hence potentially being included in a community we dread and excluded from one we admire. Identification, in other words, ‘is defined with respect to communities and forms of membership in them’ (p. 197). Negotiability, for its part, ‘is defined with respect to social configurations and our positions in them’ (p. 197). In this sense, whilst a strong identification can be analysed from the members’ reasoning, negotiability, being ‘shaped by structural relations of ownership of meaning’ (p. 197), can be considered as being severely compromised in OBY through the emphasis put on finishing the task.

Consequently, the apparent avoidance of conflict, as seen in the preceding story, is problematic particularly in terms of musical learning and the formation of a democratic learning community. According to Wenger, the ‘three dimensions of the relation by which practice is the source of coherence of a community’ are mutual engagement, a joint enterprise and a shared repertoire (p. 72). None of the characteristics, however, necessarily entail or result in homogeneity or like-mindedness. Rather, diversity and differentiation are natural, and often beneficial, parts of the communities of practice, and ‘disagreement, challenges, and competition can all be forms of participation’ (p. 77), as well as a valuable ‘learning resource’ (Wenger et al., Reference WENGER, WHITE and SMITH2009, p. 9). Or, as Sawyer (Reference SAWYER2007) argues, ‘the friction that results from multiple opinions drives the team to more original and more complex work’ (p. 71). Wenger (Reference WENGER1998) reminds us that ‘[t]he enterprise is joint not in that everybody believes the same thing or agrees with everything, but in that it is communally negotiated’ (p. 78). Likewise, Dewey (Reference DEWEY and Hickman1996, LW 7, p. 166) points out that conflict has a positive function by bringing a clearer recognition to different interests. This recognition may then lead further to ‘a challenge to inquiry – that is, to operative intelligence’ (Dewey, Reference DEWEY and Hickman1996, LW 12, p. 524). In OBY, however, there is no space for this kind of search for shared solutions (as use of intelligence). Whether deliberately or not, negotiations of meaning are labelled as being useless tiffs and thus are seen as speed bumps on the way to the destination of successfully completing the task, as exemplified in the above story. By self-censoring any sign of friction, the OBY composers settled for conformity rather than striving towards active agency, fulfilling their need for identification while sacrificing deeper ownership.

Conditions for educative collaborative composing

Although informal musical environments, such as OBY, may represent and illustrate important aspects of the community life of the society, we propose that they do not necessarily provide ideal models for the music classroom, as informal practices are rarely based on equal values or aim at similar goals to formal education. Hence, at the same time as we agree that learning can be seen as a trajectory in a community of practice instead of a separate activity (Lave & Wenger, Reference LAVE and WENGER1991; Wenger, Reference WENGER1998), we also wish to point out that not all group activities or practices in the society are particularly effective in terms of enhancing such learning that facilitates the construction of identity and an ownership of meaning. As Sawyer (Reference SAWYER2007) states, simply ‘[p]utting people into groups isn't a magical dust that makes everyone more creative’ (p. 73). Also, as Seddon's (Reference SEDDON2006) study on computer-mediated music composing showed, a collaborative environment does not guarantee collaborative engagement. Based on our analysis of the OBY community, we therefore suggest that at least the following conditions for collaborative composing may need to be considered in educational contexts.

Task-based learning communities as the basis for collaborative composing may involve limited community mechanisms

As suggested by Riel and Polin (Reference RIEL, POLIN, Barab, Kling and Gray2004), it is possible to begin the transformation of traditional music classroom instruction with the idea of a joint task. In this way classrooms may be transformed into learning communities that may even extend across grade levels and involve a variety of expertise (p. 23). However, as illustrated throughout the article, by simply emphasising the completion of a task – a collaborative composition, or an oeuvre – as the final end to collaboration, we might compromise the formation of such a community that deliberately supports the students' learning and identity work through facilitating possibilities for negotiations of meaning. Indeed, in their analysis of different kinds of learning communities, Riel and Polin hesitate to refer to task-based learning communities as communities at all, stating that in some ways task-based learning communities could be considered as ‘micro-communities’ as they fall short of sharing ‘all of the characteristics of full-blown communities’ (p. 23). As a result of the short timeline, a task-based learning community established for a specific purpose, such as a musical performance in school festivities, does not necessarily allow for the development of ‘community mechanisms such as shared discourse and shared sets of practices, values, and tools’ (p. 23).

Even within longer projects, such as OBY, where there are tools and shared practices developed that have been negotiated and discussed, the final creative product is non-negotiable and non-modifiable. Although the participants of OBY are given opportunities to contribute to the final opera score by generating musical ideas and material, ultimately the entirety of the opera's music will lie in the hands of the musical operative. Hence, membership in OBY does not necessarily designate mutual engagement, which, according to Wenger (Reference WENGER1998), ‘defines the community [of practice]’ (p. 73), and significantly surpasses the mere act of logging onto a website. Wenger argues that the first requirement for ‘being engaged in a community's practice’ is to be ‘included in what matters’ (p. 74, emphasis added) and what matters in a given community is not merely a question of a stated and static goal, like the task that forms the basis for the existence of OBY, but one of a joint enterprise. This second requirement, according to Wenger, is always ‘the result of a collective process of negotiation . . . defined by the participants in the very process of pursuing it’ (p. 77, emphasis added), which further ‘creates among participants relations of mutual accountability that become integral part of the practice’ (p. 78). Thirdly, the joint enterprise results as a shared repertoire of ‘routines, words, tools, ways of doing things . . . concepts’ (p. 83) and so on, thus creating a set of ‘resources for negotiating meaning’ (p. 82) in the community. While the OBY members do share a joint endeavour – a task that matters – as well as ways of accomplishing it, the three dimensions of a community of practice are not fully present since possibilities for negotiation are limited by the role of the operative.

In an educational setting, the cost of short-time efficiency in completing the task might become eventual weaknesses in terms of providing challenges that would allow for new levels of expertise for the students through the occurrence of ‘learning as social construction’ (p. 17). Instead of considering the successful performance of a collaborative composition at a school event as the end of a musical production, the teacher may need to consider how participation in the project could enable new levels of expertise and thus increase a sense of ownership in the classroom, school or beyond. Furthermore, established forms of musical activities and the ‘physical structure of a classroom’ (Barrett, Reference BARRETT, Miell, MacDonald and Hargreaves2005, p. 276) may inhibit new collaborative forms of learning in school. According to Barrett, even small structural changes ‘may assist in creating public and private spaces for individual, small group and large group engagement’ (p. 276).

Students' identity work and learning in collaborative composing go hand in hand

As shown above, the OBY project has provided an innovative platform for a group of people to be identified as opera composers, yet only a limited forum for constant reflection and negotiation. This has significant consequences in terms of learning in the community. As the musical operative is the final musical designer of the OBY music, the participants’ access to development as composers and experiences of meaning is compromised by the lack of chances to shape the practice of their community (see Wenger, Reference WENGER1998, p. 57). This is manifested in OBY particularly in the omission of learning through evaluation and reflection upon the process and, specifically, through revisions of their own contributions. It could be said, by paraphrasing Chapman (Reference CHAPMAN, Kimble, Hildreth and Bourdon2008), that the absence of opportunities for the OBY composers to ‘revisit their work to reflect on design and learning processes results in lost opportunities for deepening connections to learning’ (p. 41) and for organising prominent learning experiences ‘into some meaningful, coherent structure’ (p. 45). The authority of the musical operative may stir the composing process of individual participants, but with the exception of his working in cooperation with every individual OBY composer, all the other participants are working with their musical contributions alone, albeit having the possibility to discuss principles and the other participants’ general views online. By assembling the musical snippets of the individual composers, the musical operative takes on the role of a specialist who ‘knows best’ and whose point of view prevails in lieu of the collaborators’ ‘commitment to shared resources, power, and talent’ (John-Steiner et al., Reference JOHN-STEINER, WEBER and MINNIS1998, p. 776). Whilst this may be understandable as the Festival organisers needed to secure the end result, the situation closely reminds one of school projects where ‘the creativity of a group’ (Sawyer, Reference SAWYER2006, p. 148, emphasis added) is overlooked if the teacher takes the lead in favour of the creativity of the art product. Often, as Hickey (Reference HICKEY and Hickey2003) argues, ‘our controlled and hurry-up classroom culture’ (p. 34) is in contrast to the messiness and slowness required for creative thinking. For instance, the teacher may choose only the ‘best’ performers for the ‘most important’ tasks, and even ignore the contribution of those students with more modest skills and thus minimize sustained negotiation. One could argue that the emphasis put on the completion and quality of the end product endangers the pursuit of ‘a true collaboration’ in which, according to Minnis et al. (1994), ‘authority for decisions and actions resides in the group, and work products reflect a blending of all participants’ contributions’ (cited in John-Steiner et al., Reference JOHN-STEINER, WEBER and MINNIS1998, p. 776, emphasis added).

While accepting that in an educational setting the teacher as a facilitator, coach (e.g. Ehrlich, Reference EHRLICH1998, p. 494) or a mentor (Chapman, Reference CHAPMAN, Kimble, Hildreth and Bourdon2008), may not necessarily need to share the entire process of production, there are crucial educational consequences arising from not sharing the reflection on the entire process. In fact, a mentor may have an important role in promoting intentional reflection as ‘part of the design activities and resultant interactions with other learners’ (Chapman, Reference CHAPMAN, Kimble, Hildreth and Bourdon2008, p. 41). As, for instance, Collins and Halverson (Reference COLLINS and HALVERSON2009) state, systematic reflection on practice could potentially be enhanced by technology as it allows one to record performances and look back at how the task was done, hence affording people the opportunity ‘to reflect on the quality of their decisions and think about how to do better next time’ (p. 27). Moreover, as in OBY, the work and effort put into collaborative composing in educational contexts needs to be related to the students' own life values and not simply subjected and reduced to those of the teacher or institution, so that the students can imagine a sense of affinity and construct meaning, i.e. identify themselves with the task at hand and the people they are collaborating with. As Barrett (Reference BARRETT, Miell, MacDonald and Hargreaves2005) argues, this is often a challenge in school settings in which educational practices are not necessarily based on the students' ‘interest in the topic’ (p. 275). Barrett emphasises that in order to develop communities of practice in music education, one needs knowledge of the musical thoughts and actions brought to the classrooms by all participants in order ‘to promote dialogue and discussion and the interrogation of a range of perspectives’ (p. 276).

Conflicts and disagreements may be taken as a productive part of musical collaboration and community life

One educational approach that consciously deals with opening space for negotiability is the so-called ‘project approach’, or ‘grouping’ that deliberately leads students towards constant negotiations within collaborative work (e.g. Ehrlich, Reference EHRLICH1998; Simpson, Reference SIMPSON1999). This approach has not been welcomed without hesitation, since varying the division of labour is one of the characteristics that is difficult to deal with in traditional teacher-centred pedagogy in which educators wish to control what their students are learning, or when learning results are expected to be tested and therefore to be controlled by the teachers (Ehrlich, Reference EHRLICH1998, p. 499). Besides, the processes of negotiation in educational projects may allow for conflicts and disagreements that are interpreted as disruptions. However, this possibility for conflict could be seen as a necessary precondition for democracy and education into democracy. It is in this light that we understand Dewey's words: ‘there is more than a verbal tie between the words common, community, and communication’ (Dewey, Reference DEWEY and Hickman1996, MW 9, p. 7). Instead of seeing a community based on a concept of common good and like-mindedness, it should be built around the idea of a common bond, a sense of collective concern and common interests. In these kinds of communities, unity is created through activities in which there is space for conflicting views and constant negotiation that could be extended throughout educational processes. Furthermore, if, as we believe, the quality of the process of creating an art work is related to the participants’ sense of the meaningfulness of the process, and in that way to the quality of their lives as a whole (Westerlund, Reference WESTERLUND2008), the creation of collaborative art works may also require the learning of so-called ‘non-musical’ skills of collaboration, such as those of negotiation between different, even conflicting viewpoints. In this sense, the aesthetic quality of a collaboratively composed artwork never completely determines the quality of the collaborative composers’ experience, or their experience of identity.

Conclusion

Having had our point of departure in sociocultural theories of learning, by and large, this study argues that music education – ranging from general music classrooms to teacher education in universities and beyond – could be increasingly conceptualised as providing flexible arenas for the co-construction of meanings, or collaboration in creating meanings. In addition, as recently emerging web-based cultural phenomena, such as operabyyou.com, illustrate, not only creating one's own music but also distributing it publicly has become available to larger groups of people than perhaps ever before. These new forums no longer conceptualise composing as the solitary practice of individual genii, but exemplify how social configurations can be combined with the creation of musical ideas. Collaborative composing may appear in different forms in online communities, with slightly different emphases on ways of working. These practices range from musical ‘collage making’ that utilises music made and uploaded by several people onto platforms such as YouTube, communities such as mikseri.net in which people mainly work on their own compositions but make revisions to them based on the feedback received from other community members (Salavuo, Reference SALAVUO2006; Partti, Reference PARTTI2009; Partti & Karlsen, Reference PARTTI and KARLSEN2010), all the way to those such as OBY in which participants work on the same assignments as specified by a musical leader. Digital and virtual technologies enable the process of composing to become public and open up opportunities for collaboration. Hence, it is expected that these novel phenomena will soon have a greater impact also on schools, conservatories and universities that do not want to isolate themselves from fruitful and creative societal and cultural developments. However, in order for educative projects, including collaborative composing, to become inclusive orchestrations of democratic and versatile musical learning, the nature of interactions and the division of labour within collaborative communities needs to be thoroughly reflected. Acknowledging the cultural value of informal musical practices does not necessarily entail an uncritical copying of those practices in institutions of formal music education. For envisioning educationally grounded collaborative composing practices, this article has suggested that Wenger's sociocultural theory of communities of practice may offer a useful heuristic frame for reflection when designing settings that aim not only at collaborative composing but also at powerful learning and the ownership of musical meaning.

Heidi Partti (PhD, MA in Music, MA in Applied Music Psychology) works as a Post-Doc Researcher at the Sibelius Academy in Helsinki, Finland. Her research interests revolve around different kinds of music-related communities, specifically those enabled by digital and/or virtual technologies. In addition to her work as a researcher, Partti works as a musician and music teacher.

Heidi Westerlund is a Professor at the Sibelius Academy in Helsinki, Finland. She has published mainly in the field of philosophy of music education with the emphasis on multiculturalism, agency and collaborate learning. She is responsible for the doctoral program of music education at the Sibelius.