Aging is associated with unique challenges across a variety of life domains. In later years, these include physical and cognitive challenges, such as an increased likelihood of multimorbidity (Salive, Reference Salive2013), greater incidence of cognitive disorders (Fiest et al., Reference Fiest, Jette, Roberts, Maxwell, Smith and Black2016), as well as normative developmental, social, and emotional challenges, including transitioning to retirement and spousal, family, and friend bereavement (Lang & Heckhausen, Reference Lang, Heckhausen and Hoare2006). With the worldwide population aging rapidly (United Nations, 2015), the proportion of individuals preparing to face these challenges is increasing. This combination of increased longevity and greater adversity suggests that psychological resilience may play a particularly important role in later life.

Early studies of resilience originated in the developmental psychology literature with a focus on children who had experienced adverse circumstances, yet still managed to thrive (Masten & Garmezy, Reference Masten, Garmezy, Lahey and Kazdin1985; Rutter, Reference Rutter1985). However, given the many challenges associated with aging, the study of resilience is increasingly being recognized as important in later life (Harris, Reference Harris2008; Martin, Lee, & Gilligan, Reference Martin, Lee, Gilligan and Coll2019; Wild, Wiles, & Allen, Reference Wild, Wiles and Allen2013). Despite decades of quality resilience research, the literature to date lacks a consistently agreed-upon definition of the construct (e.g., Fletcher & Sarkar, Reference Fletcher and Sarkar2013). Furthermore, the term resiliency, which refers to a profile of individual characteristics and traits (Luthar, Cicchetti, & Becker, Reference Luthar, Cicchetti and Becker2000), is often used interchangeably with the term resilience, which is typically viewed as a dynamic process. Despite discrepancies in definitions and operationalization, the increasing consensus among researchers is that resilience is a process that begins with adversity, consists of a number of defining attributes, and results in positive adaptation (e.g., Gillespie, Chaboyer, & Wallis, Reference Gillespie, Chaboyer and Wallis2007; Niitsu et al., Reference Niitsu, Houfek, Barron, Stoltenberg, Kupzyk and Rice2017; Windle, Reference Windle2011). Therefore, resilience in the present study is operationalized as a dynamic process that results in positive adaptation when faced with adversity (Luthar et al., Reference Luthar, Cicchetti and Becker2000; Niitsu et al., Reference Niitsu, Houfek, Barron, Stoltenberg, Kupzyk and Rice2017) and consists of individual, environmental, and experiential defining attributes (Windle, Reference Windle2011).

Despite a myriad of challenges associated with aging, older adults generally demonstrate resilient features at greater than or equal levels to younger adults (Gooding, Hurst, Johnson, & Tarrier, Reference Gooding, Hurst, Johnson and Tarrier2011). However, previous research has indicated that the factor structures of resilience scales used with older adult populations often diverge, suggesting that resilience may manifest differently across the lifespan (Cosco, Kaushal, Richards, Kuh, & Stafford, Reference Cosco, Kaushal, Richards, Kuh and Stafford2016). Although there are several measures designed to assess resilience (e.g., Prince-Embury, Saklofske, & Vesely, Reference Prince-Embury, Saklofske, Vesely, Boyle, Saklofske and Matthews2015; Smith-Osborne & Bolton, Reference Smith-Osborne and Bolton2013), the majority were developed or intended for use with children or young adults (Windle, Bennett, & Noyes, Reference Windle, Bennett and Noyes2011). Given the qualitatively distinct challenges faced in older adulthood (e.g., death of spouse and friends, loss of social standing, declines in physical functioning; Smith & Hayslip, Reference Smith and Hayslip2012), it is necessary to develop an assessment tool that is specifically designed to measure resilience during later life. Thus, this study draws upon a theoretical model of resilience protective factors in older adulthood (Wilson, Walker, & Saklofske, Reference Wilson, Walker and Saklofske2020) with the aim of developing a resilience scale for older adults.

Measuring Resilience in Older Adults

There are many well-validated measures designed to assess resilience across the lifespan (Cosco et al., Reference Cosco, Kaushal, Richards, Kuh and Stafford2016; Pangallo, Zibarras, Lewis, & Flaxman, Reference Pangallo, Zibarras, Lewis and Flaxman2015; Prince-Embury et al., Reference Prince-Embury, Saklofske, Vesely, Boyle, Saklofske and Matthews2015; Smith-Osborne & Bolton, Reference Smith-Osborne and Bolton2013; Windle et al., Reference Windle, Bennett and Noyes2011). However, very few have been developed specifically for use in older adult samples. A recent review by Cosco et al. (Reference Cosco, Kaushal, Richards, Kuh and Stafford2016) identified only three existing adult measures that have been validated for use in an older adult population: the Connor Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC; Connor & Davidson, Reference Connor and Davidson2003), the Brief Resilient Coping Scale (BRCS; Sinclair & Wallston, Reference Sinclair and Wallston2004), and the Resilience Scale (RS; Wagnild & Young, Reference Wagnild and Young1993). The review indicated that the CD-RISC was suitable for use with older adults, demonstrating good reliability as well as convergent and discriminant validity, although the factor structure, when used with older adults, was inconsistent with the initial scale development (Lamond et al., Reference Lamond, Depp, Allison, Langer, Reichstadt and Moore2008). The BRCS demonstrated good reliability, but only one study examined this scale in an older sample, and the psychometric properties examined were limited. Additionally, the authors concluded that further supporting evidence was required to ensure the BRCS is a valid measure for use with older adults (Tomás, Melendez, Sancho, & Mayordomo, Reference Tomás, Meléndez, Sancho and Mayordomo2012). Last, while the RS has demonstrated good reliability and convergent/discriminant validity in older adult samples (Girtler et al., Reference Girtler, Casari, Brugnolo, Cutolo, Dessi and Guasco2010; Resnick & Inguito, Reference Resnick and Inguito2011; von Eisenhart Rothe et al., Reference von Eisenhart Rothe, Zenger, Lacruz, Emeny, Baumert and Haefner2013), inconsistencies were found in the factor structure across studies, which may suggest that resilience is expressed differently across age groups (Cosco et al., Reference Cosco, Kaushal, Richards, Kuh and Stafford2016), and the measure lacks key resilience protective factors (van Kessel, Reference van Kessel2013).

To date, only three published scales have been developed specifically with older adult samples, and each has limitations. The RS (Wagnild & Young, Reference Wagnild and Young1993) was theoretically grounded in interviews with older women (Wagnild & Young, Reference Wagnild and Young1990) and is currently recommended as the most suitable existing measure for use with older adults (Cosco et al., Reference Cosco, Kaushal, Richards, Kuh and Stafford2016). However, it assesses only dispositional resilience and lacks key resilience factors that are critical to resilience in older adults (e.g., relationships, social support; van Kessel, Reference van Kessel2013). The Multidimensional Individual and Interpersonal Resilience Measure (MIIRM; Martin, Distelberg, Palmer, & Jeste, Reference Martin, Distelberg, Palmer and Jeste2015) was developed by identifying protective factors from a large secondary data set, and as such was limited to the researcher-defined factors present in the archived data set, and it has yet to be validated beyond initial scale development. Last, the Hardy-Gill Resilience Scale (Hardy, Concato, & Gill, Reference Hardy, Concato and Gill2004) is an outcome-focused measure and asks participants how well they adapted after experiencing a negative event, but it does not assess what factors contribute to their resilience. Overall, while a number of existing measures may be acceptable for use with older adults, they are limited in scope. Thus, the resilience literature would benefit from a comprehensive measure that was developed specifically for an older adult population, and theoretically grounded in factors relevant to older adults.

The Resilience Scale for Older Adults

To address the need for a theoretically appropriate measure of resilience specifically tailored to an older adult population, we developed the Resilience Scale for Older Adults (RSOA). In order for resilience research to have implications for policy and for older people themselves, it needs to be conceptualized in a way that is meaningful to older adults (Bowling & Dieppe, Reference Bowling and Dieppe2005). One means of achieving this is by asking older adults what resilience means to them (Wild et al., Reference Wild, Wiles and Allen2013). Thus, the RSOA was developed using a model of resilience protective factors grounded in the qualitative literature examining resilience from older adults’ perspectives (Wilson et al., Reference Wilson, Walker and Saklofske2020). This model comprises four overarching factors and eight underlying facets; however, to enhance precision in assessment, the RSOA consists of four factors and 11 underlying facets. Specifically, Factor 1, Intrapersonal Protective Factors, encompasses individual characteristics that protect older adults in the face of adversity, and includes the following facets: Perseverance and Determination, Self-Efficacy and Independence, Purpose and Meaning, and Positive Perspective. Factor 2, Interpersonal Protective Factors, comprises the external, or environmental, protective factors important for older adults, including the following: Sense of Community, Family Support, and Friend/Neighbour Support. Factor 3, Spiritual Protective Factors, describes the protective nature of religious facets, such as Faith and Prayer. Last, Factor 4, Experiential Protective Factors, includes the impact of previous adverse experiences (Previous Adversity) and the resulting proactive behaviour (Proactivity) that protects older adults in the face of adversity.

Throughout scale construction, we adhered to DeVellis’s (Reference DeVellis2003) framework for scale development and validation, which consists of the following steps: (1) determine what you want to measure; (2) generate an item pool; (3) determine the format for measurement; (4) have the initial item pool reviewed by experts; (5) consider inclusion of validation items; (6) administer items to an appropriate sample; (7) evaluate the items; and (8) optimize scale length. In addition, we incorporated Jackson’s (Reference Jackson1984) recommendations for scale construction, which include: (1) ensuring factors are theoretically sound and well-defined; (2) generating a large item pool; (3) specifying a delineated factor structure prior to data collection; and (4) evaluating the convergent and discriminant validity of the scale.

To assess the convergent validity of the scale, variables that are anticipated to be related to resilience based on previous research have been included in the present study. Life satisfaction (e.g., Smith & Hollinger-Smith, Reference Smith and Hollinger-Smith2015), happiness (e.g., Gomez, Vincent, & Toussaint, Reference Gomez, Vincent and Toussaint2013), other measures of resilience (e.g., Karairmak, Reference Karairmak2010), depression (e.g., Laird, Krause, Funes, & Lavretsky, Reference Laird, Krause, Funes and Lavretsky2019), anxiety (e.g., Keil, Vaske, Kenn, Rief, & Stenzel, Reference Keil, Vaske, Kenn, Rief and Stenzel2017), stress (e.g., Gomez et al., Reference Gomez, Vincent and Toussaint2013), and quality of life (e.g., Manne et al., Reference Manne, Myers-Virtue, Kashy, Ozga, Kissane and Heckman2015) are all constructs that are consistently related to resilience and should theoretically be associated with increased or decreased levels of resilience.

Objectives

The present study describes the initial development and validation of the RSOA. Study 1 examined the psychometric properties of the preliminary 50 items and reduced this initial item pool to a more succinct set of 33 items. Study 2 examined the scale’s four-factor structure and provided initial convergent validity information for the final 33-item scale. Last, Study 3 confirmed the four-factor structure, provided additional convergent and concurrent validity information, and examined gender invariance.

Study 1: Item Reduction and Evaluation

In line with recommendations for self-report scale development (DeVellis, Reference DeVellis2003; Jackson, Reference Jackson1984), we initially generated a large item pool consisting of 83 items. Items were reviewed by experts (i.e., psychology clinicians), as well as senior doctoral students who were well-versed in the study of resilience and test construction. The clinicians had extensive expertise and experience, specifically with resilience scale development (e.g., Prince-Embury, Reference Prince-Embury2006; Prince-Embury, Saklofske & Nordstokke, Reference Prince-Embury, Saklofske and Nordstokke2017; Saklofske et al., Reference Saklofske, Nordstokke, Prince-Embury, Crumpler, Nugent, Vesely, Prince-Embury and Saklofske2013), and the doctoral students were experienced in developing and validating other psychological measures, as well as publishing articles focusing on resilience assessment (e.g., Wilson et al., Reference Wilson, Plouffe, Saklofske, Di Fabio, Prince-Embury and Babcock2019; Wilson & Saklofske, Reference Wilson and Saklofske2018). The reviewers were provided with the 83 items and the definitions of each factor and facet and asked to comment on item appropriateness and fit for each facet/factor, as well as content validity of the preliminary measure. Items that were deemed unsuitable (e.g., unclear, redundant, inapt) were eliminated, which resulted in the initial 50-item pool. In addition to item reduction, we evaluated the initial scale’s relationship with life satisfaction to establish preliminary convergent validity evidence. We predicted a positive relationship between the RSOA and life satisfaction.

Method

Participants and Procedure

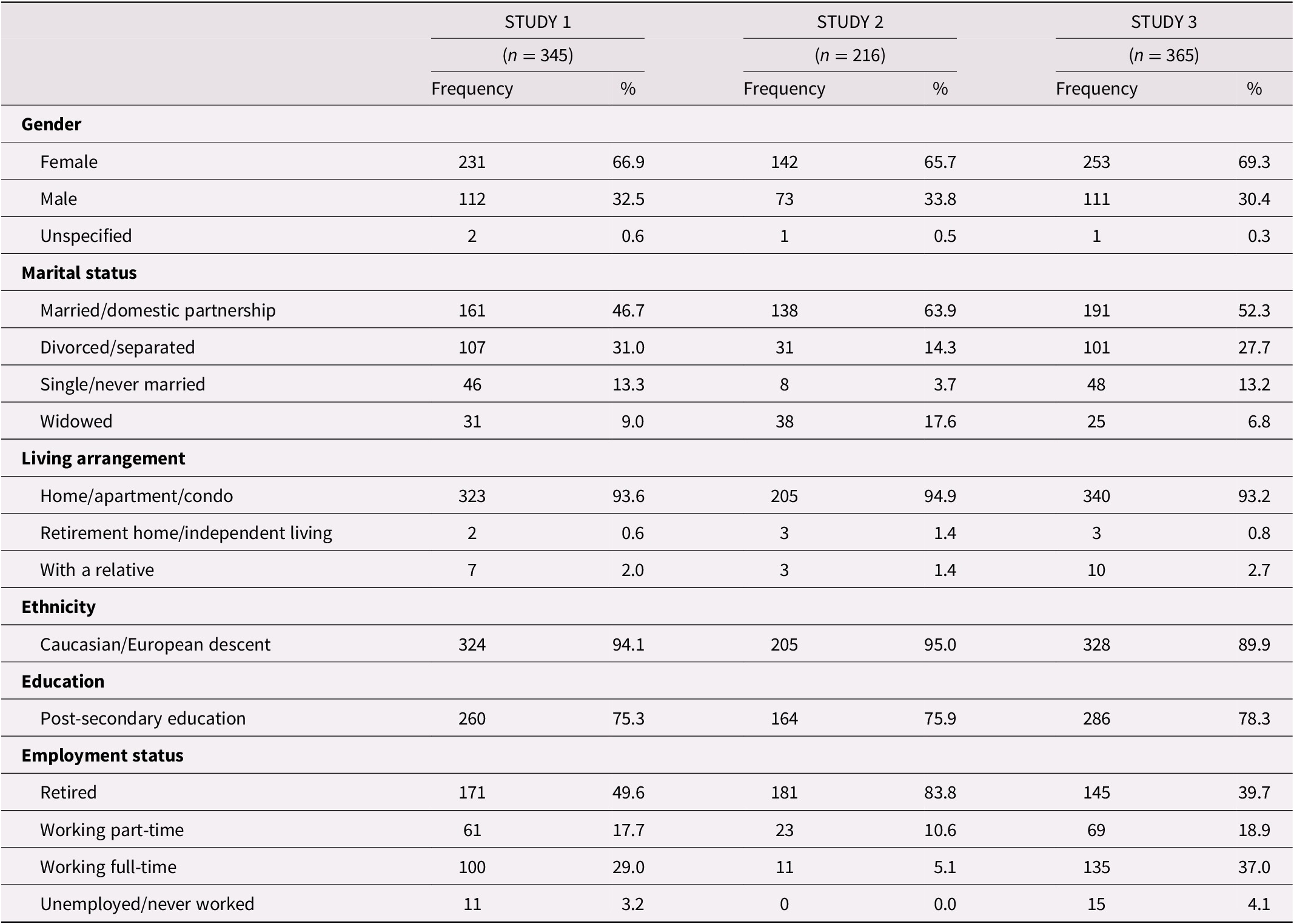

Participants were 345 individuals from Amazon’s Mechanical Turk (MTurk) residing in Canada and the United States. Participants’ ages ranged from 60 to 81 years (M age = 65.32, SD age = 4.54). See Table 1 for additional participant demographic information. A number of recent studies have utilized the MTurk participant pool to collect similar survey data from older adults (e.g., Bernhold, Gasiorek, & Giles, Reference Bernhold, Gasiorek and Giles2020; Webb, Cui, Titus, Fiske, & Nadorff, Reference Webb, Cui, Titus, Fiske and Nadorff2018). Further, one systematic review suggested that online surveys are a feasible method of collecting data with an older population (Remillard, Mazor, Cutrona, Gurwitz, & Tjia, Reference Remillard, Mazor, Cutrona, Gurwitz and Tjia2014). To identify potentially inattentive participants, the surveys in all three studies contained four instructional attention checks. Additionally, participants for all three studies completed initial cognitive screening items adapted from the orientation section of the Cognitive Assessment Screening Test (CAST; Drachman et al., Reference Drachman, Swearer, Kane, Osgood, O’Toole and Moonis1996). Through the MTurk platform, participants were invited to complete an online survey consisting of demographic questions, initial RSOA items, and a measure of life satisfaction. They were paid a small fee ($1.00 USD) for their participation.

Table 1. Summary of participant demographics for Studies 1, 2, and 3

Measures

Participants completed the preliminary 50-item RSOA. Responses ranged from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). As a measure of preliminary convergent validity, life satisfaction was assessed using the five-item Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS; Diener, Emmons, Larsen, & Griffin, Reference Diener, Emmons, Larsen and Griffin1985), which assesses global cognitive judgments of one’s life satisfaction rated on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Previous research supports the validity and reliability of the SWLS in samples of older adults with internal consistency reliabilities ranging from .79 to .85, and strong negative correlations with depression (e.g., López-Ortega, Torres-Castro, & Rosas-Carrasco, Reference López-Ortega, Torres-Castro and Rosas-Carrasco2016; Pavot, Diener, Colvin, & Sandvik, Reference Pavot, Diener, Colvin and Sandvik1991).

Data Analytic Strategy

To examine the psychometric properties of the initial 50-item pool and the reduced 33-item scale, two exploratory factor analyses (EFAs) were conducted using principal axis factoring with oblique rotation (Promax). Parallel analysis was further conducted to determine the number of factors to be retained (Horn, Reference Horn1965). Factor loadings greater than .40 were considered large (Leech, Barrett, & Morgan, Reference Leech, Barrett and Morgan2015).

Results

Exploratory Factor Analyses

First, an EFA was conducted on the initial 50-item pool. The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) index of .94 indicates the factor analysis would yield reliable results. Bartlett’s test of sphericity (Reference Bartlett1954) was significant (

![]() $ {x}^2 $

(1275) = 16142.07, p < .001), supporting that correlations between variables are significantly different from zero. Criteria used to determine the number of factors to retain were based on an a priori four-factor theoretical model, the scree plot, and parallel analysis. Consistent with the a priori theoretical model, examination of the scree plot suggested a four-factor solution, and parallel analysis recommended four factors be retained. Factor 1 (Intrapersonal) accounted for 36.10% of the variance, Factor 2 (Interpersonal) accounted for 11.24% of the variance, Factor 3 (Spiritual) accounted for 7.79% of the variance, and Factor 4 (Experiential) accounted for 4.82% of the variance among items.

$ {x}^2 $

(1275) = 16142.07, p < .001), supporting that correlations between variables are significantly different from zero. Criteria used to determine the number of factors to retain were based on an a priori four-factor theoretical model, the scree plot, and parallel analysis. Consistent with the a priori theoretical model, examination of the scree plot suggested a four-factor solution, and parallel analysis recommended four factors be retained. Factor 1 (Intrapersonal) accounted for 36.10% of the variance, Factor 2 (Interpersonal) accounted for 11.24% of the variance, Factor 3 (Spiritual) accounted for 7.79% of the variance, and Factor 4 (Experiential) accounted for 4.82% of the variance among items.

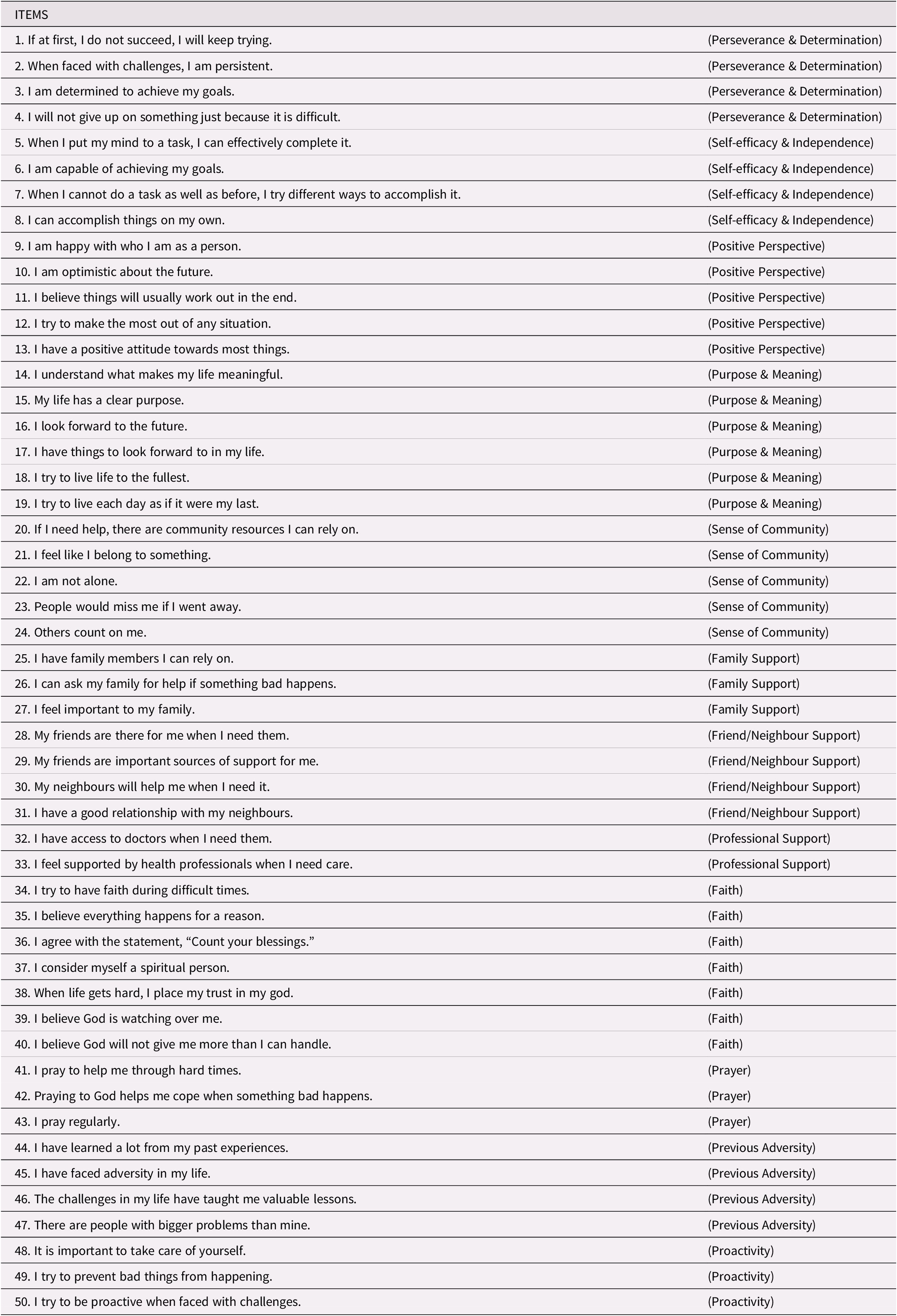

Next, items were evaluated both theoretically and empirically to reduce the scale to the most succinct number of items possible while still maintaining the underlying conceptual facets in the theoretical model. The majority of the 50 items had factor loadings greater than .40. However, the goal was to develop a measure that was parsimonious and of a moderate length to increase usability. A total of seven items were eliminated from the Intrapersonal factor due to lower factor loadings relative to the other items. Five items were discarded from the Interpersonal factor, and four items were excluded from the Spiritual factor for weaker loadings. Last, only one item was removed from the Experiential factor due to a weaker factor loading and poor theoretical fit relative to the other items in the factor, resulting in a 33-item scale. The initial 50 items and their theoretical foundations are reported in Table 2.

Table 2. Initial 50-item set with theoretical foundation

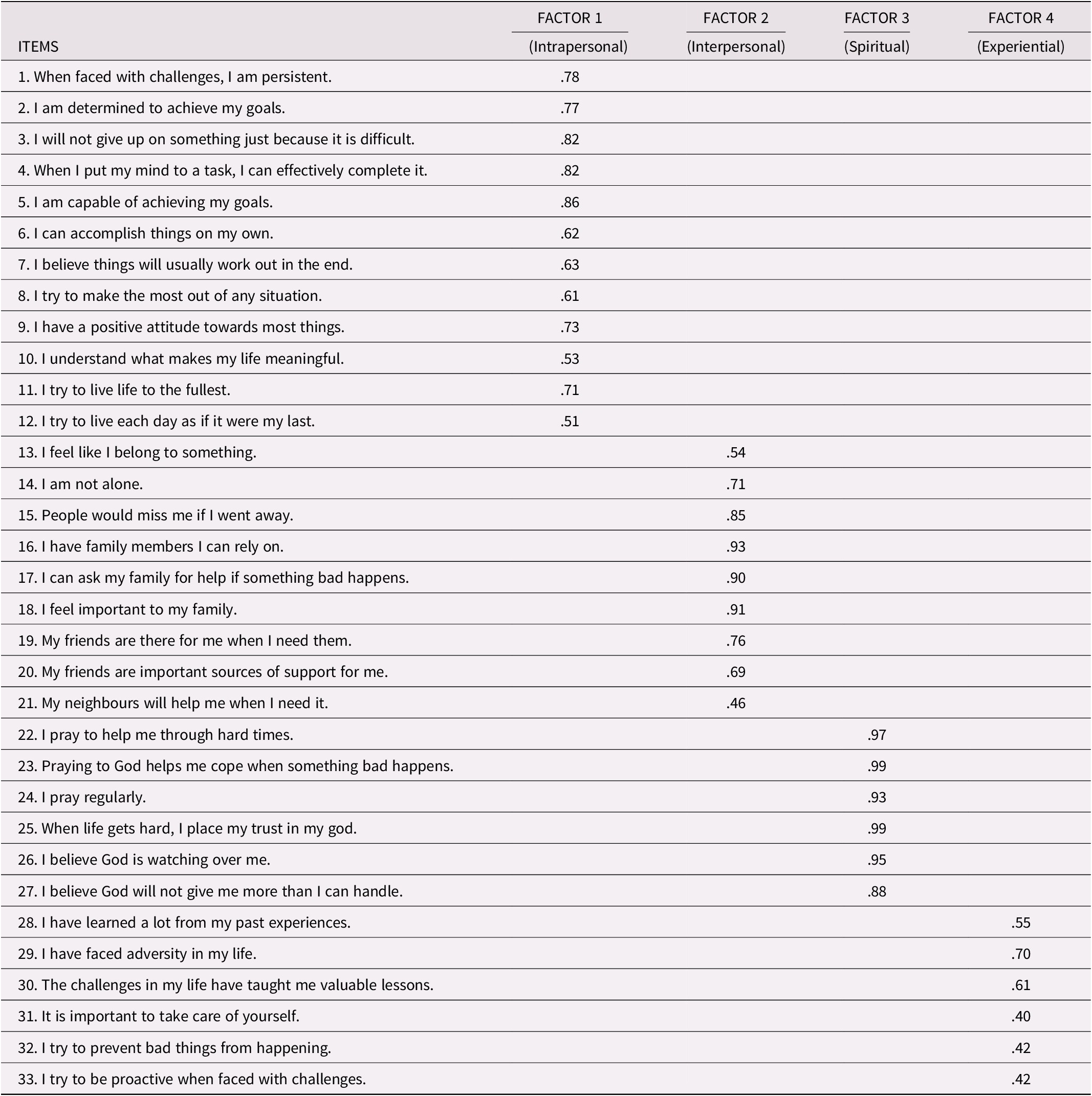

After reducing the items, separate EFAs were performed on each of the 11 facets to assess the items’ unidimensionality. All items loaded greater than .50 on their respective facets with loadings ranging from .54 to .98. We then performed an EFA using all 33 RSOA items constrained to a four-factor solution. The KMO index (.92) was acceptable, and Bartlett’s test of sphericity was significant (

![]() $ {x}^2 $

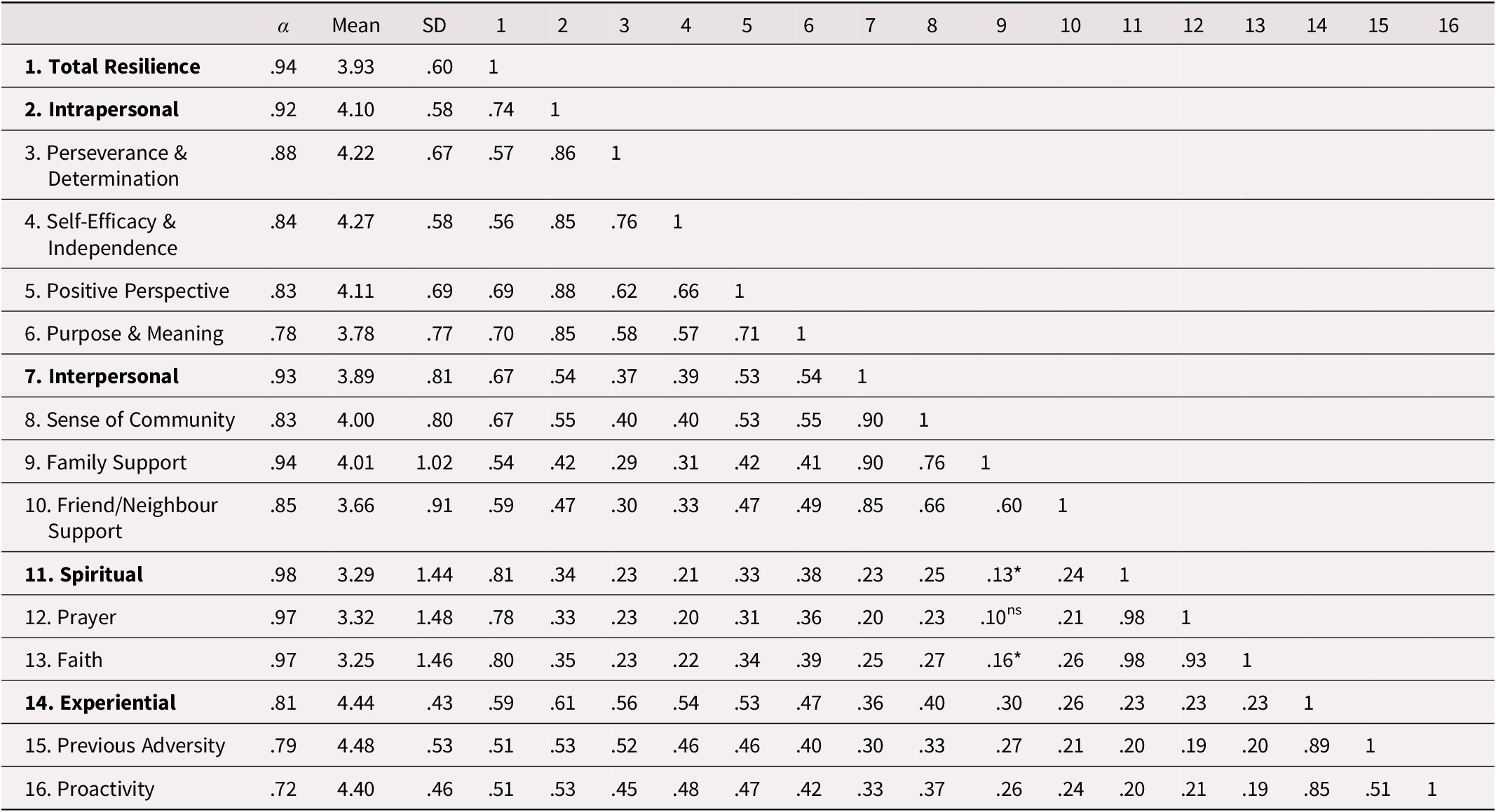

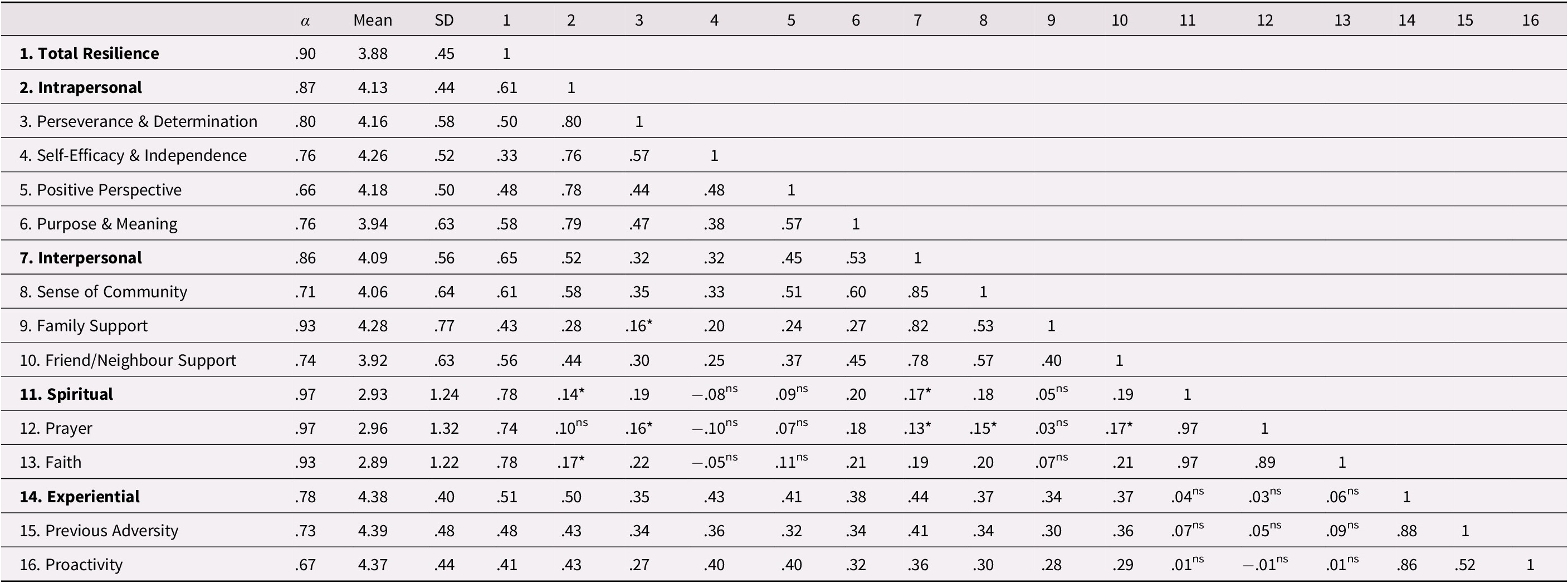

(528) = 10458.22, p < .001). Factor 1 (Intrapersonal) accounted for 36.30% of the variance, Factor 2 (Interpersonal) accounted for 13.94% of the variance, Factor 3 (Spiritual) accounted for 10.40% of the variance, and Factor 4 (Experiential) accounted for 5.19% of the variance among items. All items loaded suitably (> .40) on their corresponding factors (see Table 3). Means, standard deviations, internal consistency reliabilities, and correlations for all facets and factors for the final 33-item scale can be found in Table 4. Correlations between the factors were positive and ranged from .23 to .61. Satisfaction with Life was significantly moderately to strongly, positively correlated with Intrapersonal (r = .65), Interpersonal (r = .62), Spiritual (r = .21), and Experiential (r = .26) resilience factors.

$ {x}^2 $

(528) = 10458.22, p < .001). Factor 1 (Intrapersonal) accounted for 36.30% of the variance, Factor 2 (Interpersonal) accounted for 13.94% of the variance, Factor 3 (Spiritual) accounted for 10.40% of the variance, and Factor 4 (Experiential) accounted for 5.19% of the variance among items. All items loaded suitably (> .40) on their corresponding factors (see Table 3). Means, standard deviations, internal consistency reliabilities, and correlations for all facets and factors for the final 33-item scale can be found in Table 4. Correlations between the factors were positive and ranged from .23 to .61. Satisfaction with Life was significantly moderately to strongly, positively correlated with Intrapersonal (r = .65), Interpersonal (r = .62), Spiritual (r = .21), and Experiential (r = .26) resilience factors.

Table 3. Rotated factor loadings for the 33-item set

Table 4. Alpha reliabilities, descriptive statistics, and bivariate correlations for the RSOA factors and facets: Study 1

Notes: Factors are bolded; all correlation coefficients are significant at p < .001 unless otherwise indicated; *p < .05; ns = non-significant.

Discussion

EFA supported the unidimensionality of each of the 11 facets, and results suggest that the RSOA comprises four overarching factors, supporting the newly developed four-factor model of resilience in older adulthood (Wilson et al., Reference Wilson, Walker and Saklofske2020). Internal consistency reliability for each of the facets and factors ranged from adequate to excellent, providing initial reliability evidence for the RSOA. As a preliminary test of convergent validity, the factors were correlated with life satisfaction. As anticipated, the resilience factors reflected in the RSOA are associated with increased feelings of satisfaction with life, which is consistent with previous research conducted with older adults (e.g., Beutel, Glaesmer, Wiltink, Marian, & Brähler, Reference Beutel, Glaesmer, Wiltink, Marian and Brähler2010; Rossi, Bisconti, & Bergeman, Reference Rossi, Bisconti and Bergeman2007; Smith & Hollinger-Smith, Reference Smith and Hollinger-Smith2015). Overall, Study 1 provided initial support for the RSOA as an 11-facet, four-factor measure aligning with theoretical foundations of resilience.

Study 2: Initial Scale Validation and Validity Exploration

The aim of Study 2 was to confirm the factor structure and validate the revised 33-item RSOA in a new sample of older adults. Additionally, scores on happiness, life satisfaction, depression, anxiety, stress, and a previously validated resilience measure (i.e., Resilience Scale; Wagnild & Young, Reference Wagnild and Young1993) were correlated with scores on the RSOA to provide initial convergent validity evidence. We predicted that the RSOA would correlate positively with happiness, life satisfaction, and the Resilience Scale, and correlate negatively with depression, anxiety, and stress.

Method

Participants and Procedure

Participants consisted of 216 community-dwelling adults living in Canada ranging in age from 60 to 95 years (M age = 71.55, SD = 7.78). See Table 1 for additional participant demographic information. Participants were recruited through community organizations and through snowball sampling. Various community organizations across Canada that serve the older adult population distributed the study information to their e-mail listservs and shared the study on their websites and in their newsletters. Individuals were invited to share the study with others whom they believed may be interested. Interested participants were invited to complete an online survey consisting of demographic questions, the refined RSOA, and other measures of psychological well-being. As compensation for their participation, participants were entered into a draw for one of five $20 gift cards.

Measures

Resilience

Participants completed the revised 33-item RSOA, which consists of four overarching factors and 11 facets. In addition, as a measure of convergent validity, participants completed the Resilience Scale (RS; Wagnild & Young, Reference Wagnild and Young1993), a 25-item Likert scale that measures psychological resilience. It was originally developed using a sample of older women and is recommended as a valid measure for use with older adults (Cosco et al., Reference Cosco, Kaushal, Richards, Kuh and Stafford2016; Resnick & Inguito, Reference Resnick and Inguito2011). Cronbach’s alpha reliabilities range from .76 to .94 when used in an older population (Wagnild, Reference Wagnild2003).

Life Satisfaction

Participants completed the SWLS as described in Study 1.

Happiness

The Subjective Happiness Scale (SHS; Lyubomirsky & Lepper, Reference Lyubomirsky and Lepper1999) is a four-item measure of overall global happiness measured on a scale of 1 (not at all/less happy) to 7 (a great deal/more happy). The SHS demonstrates excellent reliability in an older adult sample with coefficient alphas of .90 (Angner, Ray, Saag, & Allison, Reference Angner, Ray, Saag and Allison2009) and ranging from .79 to .94 (Lyubomirsky & Lepper, Reference Lyubomirsky and Lepper1999). The SHS is positively correlated with measures of life satisfaction (Luchesi et al., Reference Luchesi, de Oliveira, de Morais, de Paula Pessoa, Pavarini and Chagas2018) and other happiness measures when examined with older adults (Lyubomirsky & Lepper).

Depression, Anxiety, and Stress

The Depression Anxiety and Stress Scale (DASS-21; Lovibond & Lovibond, Reference Lovibond and Lovibond1995) includes 21 items that participants respond to on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (did not apply to me) to 3 (applied to me very much most of the time), based on feelings over the past week. Previous research has demonstrated good reliability evidence for the DASS-21 in older adult samples with factor alpha coefficients ranging from .68 to .90 (Gloster et al., Reference Gloster, Rhoades, Novy, Klotsche, Senior, Kunik and Stanley2008; Wood, Nicholas, Blyth, Asghari, & Gibson, Reference Wood, Nicholas, Blyth, Asghari and Gibson2010). The DASS-21 also demonstrates excellent convergent validity with negative correlations between the DASS-21 and measures of social functioning and general health (Wood et al., Reference Wood, Nicholas, Blyth, Asghari and Gibson2010), as well as positive correlations between DASS-21 and worry and negative affect (e.g., Gloster et al., Reference Gloster, Rhoades, Novy, Klotsche, Senior, Kunik and Stanley2008).

Data Analytic Strategy

Bivariate correlation analyses were conducted to examine the convergent validity of the RSOA. Multiple confirmatory factor analyses (CFA) were conducted to examine the dimensionality of the RSOA at the item and facet level (Mplus Version 7.4; Muthén & Muthén, Reference Muthén and Muthén1998–2012). Maximum likelihood robust (MLR) estimator was used to correct standard errors for non-normality in the data. To examine model fit, the root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA), comparative fit index (CFI), Tucker–Lewis index (TLI), and standardized root-mean-square residual (SRMR) were used. RMSEA values close to .06 indicate good fit, values between .07 and .08 indicate acceptable fit, values between .08 and .10 are indicative of marginal fit, and values greater than .10 indicate poor fit. CFI and TLI values of .95 or larger represent excellent model fit, and values between .90 and .95 represent acceptable fit. SRMR values less than .08 indicate acceptable fit (Hu & Bentler, Reference Hu and Bentler1998).

Results

Descriptive Statistics and Convergent Validity

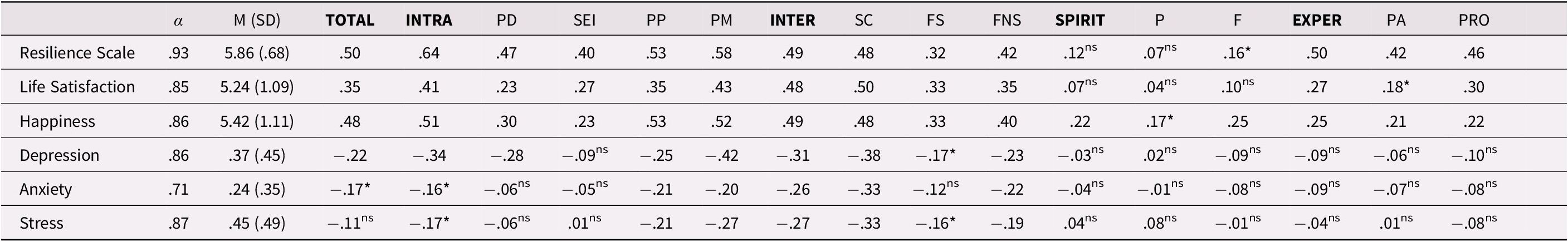

Descriptive statistics, internal consistency reliabilities, and bivariate correlations for the RSOA factors and facets can be found in Table 5. Skewness and kurtosis values were in the acceptable range for all study variables, with the exception of anxiety, which was positively skewed and positively kurtotic (Kline, Reference Kline2011). Cronbach’s alpha reliabilities for the RSOA factors ranged from acceptable to excellent, ranging from .78 (Experiential) to .97 (Spiritual). Facet internal consistencies mostly ranged from acceptable to excellent (.71 to .97), with the exception of the Positive Perspective (.66) and Proactivity (.67) facets.

Table 5. Alpha reliabilities, descriptive statistics, and bivariate correlations for the RSOA factors and facets: Study 2

Notes: Factors are bolded; all correlation coefficients are significant at p < .001 unless otherwise indicated; *p < .05; ns = non-significant.

Each of the RSOA factors were moderately to strongly, positively correlated with one another, with the exception of the Spiritual factor, which was only weakly, positively correlated with Intrapersonal and Interpersonal factors, and not significantly correlated with the Experiential factor. Further, the Spiritual factor and facets were weakly or non-significantly correlated with the other facets. The Intrapersonal, Interpersonal, and Experiential factors were moderately to strongly, positively correlated with life satisfaction, the Resilience Scale (Wagnild & Young, Reference Wagnild and Young1993) scores, and subjective happiness. However, the Spirituality factor was only significantly, positively correlated with subjective happiness (see Table 6). Depression, anxiety, and stress were all weakly, negatively correlated with the Interpersonal and Intrapersonal factors, but not significantly correlated with the Spiritual or Experiential factors.

Table 6. Alpha reliabilities, descriptive statistics, and bivariate correlations: Study 2 RSOA factors and facets and external variables

Notes: Intra = Intrapersonal; PD = Perseverance & Determination; SEI = Self-efficacy & Independence; PP = Positive Perspective; PM = Purpose & Meaning; Inter = Interpersonal; SC = Sense of Community; FS = Family Support; FNS = Friend/Neighbour Support; Spirit = Spirituality; P = Prayer; F = Faith; Exper = Experiential; PA = Previous Adversity; PRO = Proactivity; Resilience Scale, Life Satisfaction and Happiness are rated on a scale of 1-7; Depression, Anxiety and Stress are rated on a scale of 0-3; All correlation coefficients are significant at p < .001 unless otherwise indicated; *p < .05; ns = non-significant.

Item-Level Confirmatory Factor Analyses

To assess the unidimensionality of each RSOA facet, 11 separate CFA models were conducted at the item level. We used the weighted least squares mean and variance-adjusted estimator to account for the ordinal nature of the data. Overall, items loaded strongly onto their respective facets with standardized loadings ranging from .418 (Friends and Neighbours) to .995 (Prayer). One standardized item loading on the Prayer facet had a value of 1.001 with a negative residual variance, indicating presence of a Heywood case (Dillon, Kumar, & Mulani, Reference Dillon, Kumar and Mulani1987). A Heywood case occurs when an indicator has a negative variance estimate (Harman, Reference Harman1971). This was likely due to the strong correlation of .997 between items 1 and 2 on the Prayer facet. However, in the set of analyses described in the following section, indicators represented aggregates of all items within a facet, which eliminated the issue of the Heywood case.

Facet-Level Confirmatory Factor Analyses

We used CFA to evaluate the factor structure of the full RSOA at the facet level with MLR estimation. Overall, the fit of the model was acceptable: χ2(38) = 89.780, p < .001, RMSEA = .079 [90% confidence interval = .058 to .101], CFI = .935, TLI = .906, SRMR = .057. Each of the facets loaded strongly onto their corresponding factors, with standardized loadings ranging from .581 (Family Support on Interpersonal) to .880 (Sense of Community on Interpersonal). However, Faith had a standardized loading of 1.105 on the Spirituality factor with a negative residual variance. This is because latent variables with only two indicators (i.e., Prayer and Faith) are not identified. One solution is to constrain these two factor loadings to equality (Kenny, Kashy, & Bolger, Reference Kenny, Kashy, Bolger, Gilbert, Fiske and Lindzey1998). This procedure conceptually decomposes a correlation between the two indicators as their loadings on a common factor. Therefore, we ran a second model constraining the Spirituality and Experiential loadings to equality. This model also fit the data well: χ2(40) = 88.589, p < .001, RMSEA = .075 [90% confidence interval = .065 to .106], CFI = .939, TLI = .916, SRMR = .061. Again, the facet indicators loaded strongly onto their corresponding factors, with standardized loadings ranging from .580 (Family Support on Interpersonal) to .984 (Faith on Spirituality).

Discussion

The unidimensionality of each of the 11 facets was assessed separately at the item level, using CFA and findings indicated that each facet was homogeneous. Furthermore, at the facet level, results supported the multidimensional four-factor structure with 11 underlying facets. Internal consistency reliability values ranged from adequate to excellent for each factor and most facets, with the exception of the Positive Perspective and Proactivity facets, which had borderline internal consistencies. However, this is likely due to the limited number of items per facet (Cortina, Reference Cortina1993).

Consistent with previous research (e.g., Beutel et al., Reference Beutel, Glaesmer, Wiltink, Marian and Brähler2010; Gomez et al., Reference Gomez, Vincent and Toussaint2013), scoring higher on the Intrapersonal, Interpersonal, and Experiential subscales was associated with greater satisfaction with life, greater happiness, and greater resilience as measured by the Resilience Scale (Wagnild & Young, Reference Wagnild and Young1993). Furthermore, consistent with previous studies, higher scores on the Spiritual subscale were associated with higher happiness scores (e.g., Rowold, Reference Rowold2011). However, the Spiritual factor was not significantly associated with the other convergent validity variables. Although spirituality is consistently, positively related to resilience in the literature (e.g., Vahia et al., Reference Vahia, Depp, Palmer, Fellows, Golshan and Thompson2011), the theoretical underpinnings of the Resilience Scale (Wagnild & Young, Reference Wagnild and Young1993) do not include spiritual components, and perhaps do not align well with the specific facets of Prayer and Faith conceptualized in the RSOA. Furthermore, it is plausible that, although spirituality serves as a protective factor during difficult times, it may not be indicative of overall global life satisfaction.

Last, lower depression, anxiety, and stress scores were not associated with Spiritual or Experiential scores. Previous research has indicated that only certain aspects of spirituality (i.e., daily spiritual experiences and congregation) are related to depression and anxiety in older adults, whereas values, beliefs, and private religious practices are not (Bush et al., Reference Bush, Jameson, Barrera, Phillips, Lachner and Evans2012). The Faith and Prayer facets of the RSOA more closely align with components of spirituality that are unrelated to depression and anxiety in previous work, which may explain the lack of association in the present study. Finally, it may be that the evaluation of previous life adversity and proactive behaviours found in the Experiential factor is unrelated to the short-term evaluation of state depression, anxiety, and stress over the course of one week as assessed by the DASS-21 (Lovibond & Lovibond, Reference Lovibond and Lovibond1995). Overall, Study 2 provides further support for the four-factor, 11-facet structure of the RSOA and offers promising initial convergent validity evidence.

Study 3: Additional Scale Validation and Gender Invariance Analysis

Study 3 further validated the RSOA by examining and confirming the factor structure in a third sample of older adults. Convergent validity information was provided by correlating RSOA scores with perceived stress, and concurrent validity was examined by correlating RSOA scores with quality of life. Quality of life was chosen as an indicator of concurrent validity because research has demonstrated it is the primary outcome or consequence of resilience (Hicks & Conner, Reference Hicks and Conner2014). We predicted that the RSOA would be negatively correlated with perceived stress and positively correlated with quality of life.

Method

Participants and Procedure

Participants consisted of 365 individuals from MTurk residing in Canada and the United States. They ranged in age from 55 to 82 years (M age = 64.01, SD age = 5.31). See Table 1 for additional participant demographic information. Participants of ages 55 and older were included in order to acquire an adequately large sample of males to allow for gender invariance analyses. Participants were invited to complete an online survey consisting of demographic questions, the RSOA, and measures of quality of life and perceived stress through the MTurk platform. They were paid a small fee ($1.00 USD) for their participation.

Measures

Resilience

Participants completed the RSOA described in Study 2.

Quality of Life

Quality of life was assessed using the Older People’s Quality of Life Questionnaire – Brief Version (OPQLQ-Brief; Bowling, Hankins, Windle, Bilotta, & Grant, Reference Bowling, Hankins, Windle, Bilotta and Grant2013). Participants responded to 13 items assessing quality of life across life domains, including health, social participation, and psychological and emotional well-being. The items were developed based on qualitative research examining older adults’ views of what is an acceptable quality of life (Bowling, Reference Bowling2009; Bowling & Stenner, Reference Bowling and Stenner2011). Participants responded to items on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Previous research has indicated that the OPQLQ-Brief has good validity and reliability and is suitable for use in an older adult population (Bowling et al., Reference Bowling, Hankins, Windle, Bilotta and Grant2013; Kaambwa et al., Reference Kaambwa, Gill, McCaffrey, Lancsar, Cameron and Crotty2015).

Perceived Stress

Perceived stress was assessed using the 10-item Perceived Stress Scale (PSS; Cohen, Kamarck, & Mermelstein, Reference Cohen, Kamarck and Mermelstein1983), which assesses participants’ perceived levels of global stress over the past month. Participants responded to items on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (very often). The PSS has shown to be suitable for use with an older adult sample with a Cronbach’s alpha reliability value of .83 and excellent convergent/discriminant validity (Ezzati et al., Reference Ezzati, Jiang, Katz, Sliwinski, Zimmerman and Lipton2014, Hamarat et al., Reference Hamarat, Thompson, Zabrucky, Steele, Matheny and Aysan2001; Kwag, Martin, Russell, Franke, & Kohut, Reference Kwag, Martin, Russell, Franke and Kohut2011).

Data Analytic Strategy

Bivariate correlations between the RSOA, quality of life, and perceived stress were conducted to examine the convergent and concurrent validity of the RSOA. CFA was conducted to examine the dimensionality of the RSOA at the facet level in a new sample using the same methods and statistical criteria applied in Study 2. To evaluate gender invariance of the RSOA, a series of nested models were tested and compared. First, the configural model was assessed to confirm that the number of factors was equivalent across groups. Next, the metric model was evaluated, which indicates whether the factor loadings are the same across groups. Finally, scalar invariance was tested, which indicates whether the intercepts are invariant across groups. If scalar invariance is satisfied, latent means can be reliably compared across groups (Cheung & Rensvold, Reference Cheung and Rensvold2002). All invariance tests utilized maximum likelihood estimator, and nested models were compared using χ2, CFI, and RMSEA difference tests. CFI difference values less than or equal to .01 and RMSEA difference values less than or equal to .01 indicate non-significant differences in the models (Chen, Reference Chen2007; Cheung & Rensvold, Reference Cheung and Rensvold2002).

Results

Descriptive Statistics and Convergent Validity

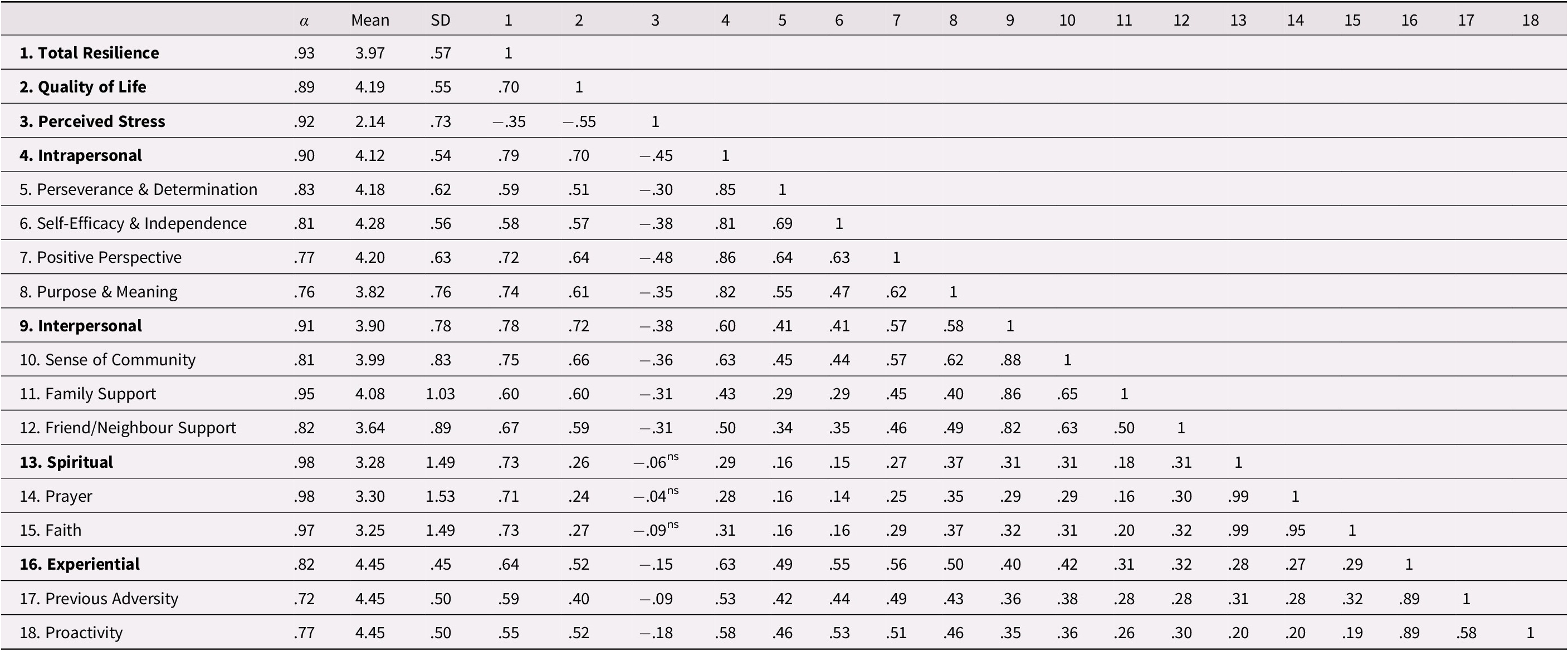

Descriptive statistics, internal consistency reliabilities, and bivariate correlations for the RSOA factors and facets are included in Table 7. Skewness and kurtosis values were in the acceptable range for all study variables (Kline, Reference Kline2011). Cronbach’s alpha reliabilities for the RSOA factors ranged from good-to-excellent ranging from .82 (Experiential) to .98 (Spiritual). Facet internal consistencies also ranged from acceptable to excellent (.72 to .98). Preliminary analyses indicated participants of ages 55 to 59 years did not differ significantly from those of ages 60 and older on RSOA factors or other demographic variables, and therefore, these individuals were included in the final sample.

Table 7. Alpha reliabilities, descriptive statistics, and bivariate correlations for the RSOA factors and facets: Study 3

Notes: Factors are bolded; all correlation coefficients are significant at p < .001 unless otherwise indicated; ns = non-significant.

Each of the RSOA factors were moderately to strongly, positively correlated with one another, with the exception of the Spiritual factor, which was weakly, positively correlated with Intrapersonal, Interpersonal, and Experiential factors. Quality of life was moderately to strongly, positively correlated with total resilience and the Intrapersonal, Interpersonal, and Experiential factors, and weakly, positively correlated with the Spiritual factor. Perceived stress was weakly to moderately, negatively correlated with total resilience and the Interpersonal, Intrapersonal, and Experiential factors, but not significantly correlated with the Spiritual factor.

Facet-Level Confirmatory Factor Analyses

We used CFA to once again evaluate the factor structure of the RSOA at the facet level. Overall, the fit of the model was acceptable: χ2(38) = 122.443, p < .001, RMSEA = .078 [90% confidence interval = .063 to .094], CFI = .954, TLI = .934, SRMR = .049. Each of the facets loaded strongly onto their corresponding factors, with standardized loadings ranging from .70 (Friend and Neighbour Support on Interpersonal) to .93 (Prayer on Spirituality). However, similar to Study 2, Faith had a standardized loading of 1.014 on the Spirituality factor with a negative residual variance. As in Study 2, we ran a second model constraining the Spirituality and Experiential loadings to equality to account for the latent variables only possessing two indicators. This model also fit the data well: χ2(40) = 125.048, p < .001, RMSEA = .076 [90% CI = .061 to .092], CFI = .954, TLI = .936, SRMR = .051. Again, facet indicators loaded strongly onto their corresponding factors, with standardized loadings ranging from .70 (Friend and Neighbour Support on Interpersonal) to .99 (Faith on Spirituality).

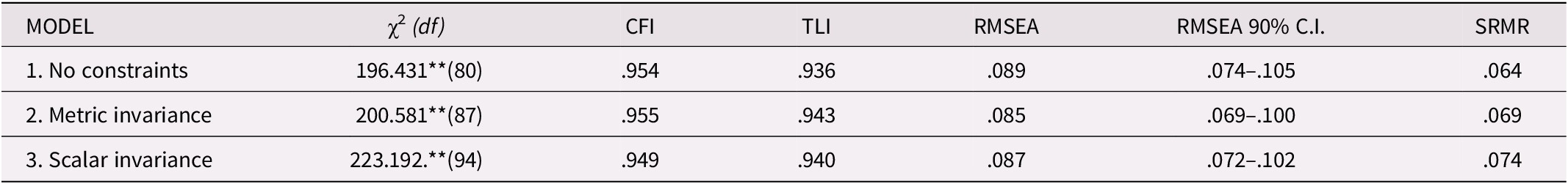

Gender Invariance

To allow for meaningful comparisons across gender, the RSOA factor structure should demonstrate invariance (Reise, Waller, & Comrey, Reference Reise, Waller and Comrey2000). Therefore, a series of nested models were tested to examine gender invariance of the RSOA (see Table 8). Overall configural model fit was acceptable: χ2(80) =196.43, p < .001, RMSEA = .089 [90% CI = .074 = .105], CFI = .954, TLI = .936, SRMR = .064; χ2, CFI, and RMSEA difference tests showed no significant differences in fit between the metric and configural model: Δχ2(7) = 4.15, p > .05, ΔCFI = .001, ΔRMSEA = .004. Thus, factor loadings did not significantly differ across men and women. When comparing differences between metric and scalar models, the χ2 difference test showed that the scalar model fit significantly worse than the metric model, Δχ2(7) = 22.61, p < .01. However, the CFI and RMSEA difference tests revealed that the scalar model was not significantly different from the metric model, ΔCFI = .006, ΔRMSEA = .002. Thus, we could reliably compare latent means. Women and men were not significantly different on Intrapersonal (Δm = .16, p = .158) or Interpersonal (Δm = .09, p = .468) factors, whereas women had higher latent means than men on the Spiritual (Δm = .61, p = < .001) and Experiential factors (Δm = .49, p < .001).

Table 8. Gender invariance fit indices

Note: **p < .001.

Discussion

Once again, results supported the overarching four-factor structure and 11 underlying facets of the RSOA. Internal consistency reliability ranged from good-to-excellent for each of the four factors and ranged from adequate-to-excellent for the facets. However, similarly to Study 2, perceived stress was not associated with the Spiritual factor. In previous research, spirituality has been implicated as an important moderating variable for coping with stress and adversity (e.g., Keefe et al., Reference Keefe, Affleck, Lefebvre, Underwood, Caldwell and Drew2001; Whitehead & Bergeman, Reference Whitehead and Bergeman2012) but may not play a direct role in reducing specific feelings of stress.

Results indicated that higher scores on all RSOA factors and its total score were associated with greater quality of life, which is consistent with studies that have indicated that quality of life is a primary outcome of resilience (e.g., Hicks & Conner, Reference Hicks and Conner2014). Last, results suggest that the factor structure is the same across genders; however, women demonstrated higher latent mean scores on the Spiritual and Experiential factors compared with men. This is consistent with a large body of previous research that indicates women consistently score higher than men on spirituality (e.g., Bailly et al., Reference Bailly, Martinent, Ferrand, Agli, Giraudeau and Gana2018; Brown, Chen, Gehlert, & Piedmont, Reference Brown, Chen, Gehlert and Piedmont2013; Singh & Bisht, Reference Singh and Bisht2019; see Francis & Penny, Reference Francis, Penny and Saroglou2013, for a review and discussion), and that women are more likely to report having experienced five or more adverse life events compared with men (Seery, Holman, & Silver, Reference Seery, Holman and Silver2010). Overall, Study 3 confirmed the structure of the RSOA, provided support for invariance across gender, and offered additional convergent and concurrent validity findings.

General Discussion

This study aimed to develop and provide initial validity evidence for a multidimensional measure of resilience protective factors in older adulthood that is grounded in qualitative research (Wilson et al., Reference Wilson, Walker and Saklofske2020). The three studies presented largely provided support for the 11-facet, four-factor (Intrapersonal, Interpersonal, Spiritual, Experiential) structure of the RSOA; however, one unanticipated consistent finding across the three studies was the weak or non-existent relationship between the Spiritual factor and its corresponding facets with other components of the RSOA. One possible explanation is that many individuals may not identify as generally spiritual people but may draw on religion and faith during difficult times when they feel their personal resources are inadequate (Faigin & Pargament, Reference Faigin, Pargament, Resnick, Gwyther and Roberto2011; Pargament, Reference Pargament1997). Therefore, spirituality may serve as a dormant protective factor that is not at the forefront daily but, instead, may become particularly relevant when faced with major adversity. Similarly, spirituality may serve as a relevant but not necessary component of resilience in older adults. That is, individuals who are highly spiritual draw on their faith as a source of strength, but those who are not spiritual may not necessarily experience resilience to a lesser degree. Additional research is needed to determine when spirituality plays a more critical role as a resilience protective factor and whether differences exist between spiritual and non-spiritual individuals in terms of positive adaptation.

The RSOA: A New Measure of Resilience in Older Adulthood

The RSOA is a promising new measure of resilience protective factors in older adults. The RSOA was developed from a model that is grounded in qualitative data collected from older adults across a variety of populations and contexts (Wilson et al., Reference Wilson, Walker and Saklofske2020). This is important because previous research has indicated that older adults’ criterion may diverge from researcher conceptualizations (Cosco, Prina, Perales, Stephan, & Brayne, Reference Cosco, Prina, Perales, Stephan and Brayne2014; Strawbridge, Wallhagen, & Cohen, Reference Strawbridge, Wallhagen and Cohen2002; Von Faber et al., Reference Von Faber, Bootsma-van der Wiel, van Exel, Gussekloo, Lagaay and van Dongen2001). Further, in order for research and policy efforts pertaining to older adulthood to be relevant to this population, it is critical to have a measure that is appropriate and meaningful to older adults themselves (Bowling & Dieppe, Reference Bowling and Dieppe2005). By being informed by older adults’ views of what factors contribute to their resilience, the RSOA assesses those factors reported to be most applicable in describing resilience. This is a unique strength of the RSOA in contrast to other measures that have their basis in researcher-driven conceptualizations from the quantitative literature (e.g., MIIRM; Martin et al., Reference Martin, Distelberg, Palmer and Jeste2015; CD-RISC; Connor & Davidson, Reference Connor and Davidson2003).

From a practical consideration, the RSOA is a relatively brief, comprehensive measure and is flexible in that it can identify protective factors at the factor or facet level, as well as provide a total overall protective factor score. This allows researchers and clinicians to use the RSOA as a tool to assess specific protective facets, or to obtain a general overall assessment of combined protective factors. While a number of protective factors in the RSOA are similar to those reflected in other adult resilience scales, the breadth of the facets and factors presented in the RSOA exceeds those of existing measures. For instance, the importance of previous experience and behaving proactively considered to be factors relevant to resilience in older adults are major components assessed by the RSOA. These factors are recognized as important to resilience in older adults (Bolton, Praetorius, & Smith-Osborne, Reference Bolton, Praetorius and Smith-Osborne2016; Wilson et al., Reference Wilson, Walker and Saklofske2020); however, they are essentially non-existent in other validated resilience measures, such as the RS (Wagnild & Young, Reference Wagnild and Young1993) and the MIIRM (Martin et al., Reference Martin, Distelberg, Palmer and Jeste2015).

Similarly, social support has been identified as a key protective factor across the lifespan (Masten & Wright, Reference Masten, Wright and Reich2009) and may be particularly relevant to resilience in later life (Wilson et al., Reference Wilson, Walker and Saklofske2020), however, this factor is severely under-represented in existing measures (i.e., CD-RISC; Connor & Davidson, Reference Connor and Davidson2003) or not represented at all (i.e., RS; Wagnild & Young, Reference Wagnild and Young1993). Last, the RSOA includes a Spiritual factor, which is frequently mentioned as a relevant component of resilience described by older adults (e.g., Kinsel, Reference Kinsel2005), but again, is infrequently included in other measures of resilience. Although the findings presented here suggest the Spiritual factor requires further analysis as a core resilience protective factor, this RSOA factor may still be useful when spirituality appears to be relevant to the assessment and understanding of resilience (e.g., researchers particularly interested in the contribution of spirituality to resilience; highly spiritual populations). Overall, none of the current resilience measures comprehensively assess the major resilience protective factors identified as important by older adults (Wilson et al., Reference Wilson, Walker and Saklofske2020). Thus, the RSOA provides a novel addition to this literature by providing a measure that has the depth and breadth to assess some of the key and more relevant protective factors in older adulthood.

This measure is intended for use by researchers, clinicians, and support workers who work closely with older adults. Having a theoretically appropriate instrument will allow researchers to improve their understanding of resilience in older adults by ensuring the measurement tool is suitable for this population. Additionally, the measure may be useful for clinicians to assess varying domains of protective factors that contribute to an individual’s resilience. It is recommended that approaches to resilience interventions in clinical settings be personalized and tailored to individual needs (Mancini & Bonanno, Reference Mancini and Bonanno2006; Mancini & Bonanno, Reference Mancini and Bonanno2009). Thus, administering the RSOA will help elucidate which protective facets and factors are strong and which domains may require greater clinical focus to increase positive adaptation in the face of adversity. As a more general application, the RSOA may be administered alongside wellness assessments provided in retirement homes or senior-living settings (Edelman, O’Brien, Loftus, & Engel, Reference Edelman, O’Brien, Loftus and Engel2010) to identify residents who may benefit from programs and services aimed at enhancing resilience. Last, this measure may be a valuable addition to prevention and intervention programs (e.g., Woods et al., Reference Woods, Williams, Diep, Parker, James and Diggle2020) designed to enhance resilience in an older population by providing an appropriate tool for tracking progress over the course of the program.

Limitations and Future Directions

The findings of the present study should be considered in light of its limitations. First, this measure is intended to provide a multidimensional assessment of protective factors and does not purport to assess specific risk and vulnerability factors that may play a role in the resilience process. Including additional screening questions (e.g., health status, financial status) during assessments may provide a more comprehensive evaluation of all factors contributing to an individual’s resilience. Second, the measures in the present study were completed exclusively online. Although previous research indicates online surveys are a useful measure of data collection for older adults (Remillard et al., Reference Remillard, Mazor, Cutrona, Gurwitz and Tjia2014), this method shares similar limitations (e.g., lack of generalizability, convenience sample) with online methods used with other populations. Furthermore, there may be mean differences in resilience between those who are able to complete surveys online and those who are not. Future research should aim to administer the RSOA to groups of older adults who may not have access to a computer so that meaningful comparisons can be made.

The mean age for each sample was on the younger end of the “older adult” spectrum (M age range = 64.01 to 71.55 years), and therefore the results may not generalize to samples of the oldest-old. Very old age is associated with numerous challenges that may impact how resilience is expressed (Staudinger, Marsiske, & Baltes, Reference Staudinger, Marsiske, Baltes, Cicchetti and Cohen1995), therefore future research is needed with a more varied older adult age group to examine how the RSOA functions across older adulthood. Additionally, the samples in the present studies consisted largely of well-educated, Caucasian individuals from North America, which limits the generalizability of these findings. It is likely that the adversities experienced by participants in the present study are not representative of the broader older adult population, and similarly, the factors that contribute to resilience may differ for older individuals of varying ethnicities and levels of education. Future research needs to validate the RSOA with more diverse samples (e.g., ethnically diverse, lower socioeconomic status, individuals with disabilities, non-community dwelling individuals). Further, while the RSOA is based on a model developed from research conducted with several diverse samples across a number of countries (Wilson et al., Reference Wilson, Walker and Saklofske2020), it remains unknown whether the RSOA generalizes to non-Western samples. Last, the present studies are cross-sectional in nature, and longitudinal studies are needed to examine the predictive utility of the RSOA.

Conclusion

In order to fully assess resilience in an older adult population, further work is needed to develop a cohesive compendium that also considers adversity and risk factors, and broader social, cultural, and economic contexts. Nevertheless, this collection of studies focuses on assessing protective factors, a critical component of the resilience process for which valid assessment in the aging literature is lacking. Although further validation is needed, the RSOA is a promising new multidimensional measure that may offer a number of theoretical and applied uses for examining resilience protective factors in an older adult population.

Competing interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare.