Moral reasoning has been a focal point of psychological science throughout time, as well as the starting point of socio-psychological problematics. Early attempts to negotiate morality, were focused almost exclusively on the benefit-harm binary (Gilligan, Reference Gilligan1982; Hoffman, Reference Hoffman1982; Kohlberg, Reference Kohlberg and Goslin1969; Turiel, Reference Turiel1983) and ignored the importance of collectivity, were therefore considered to be unilaterally aligned with Western norms (Shweder et al., Reference Shweder, Much, Mahapatra, Park, Brandt, Rozin, Brandt and Rozin1997). In the search for a definition of universal validity, Haidt and Joseph (Reference Haidt and Joseph2004) developed moral foundations theory, by drawing on, evidence from anthropological studies (see Shweder, Reference Shweder2008), evolutionary research (see de Waal et al., Reference de Waal, Macedo and Ober2006) and social psychology (see Fiske, Reference Fiske1991; Schwartz, Reference Schwartz1990). Many recent studies have focused on critically evaluating and assessing this theory (see for example: Graham et al., Reference Graham, Haidt, Koleva, Motyl, Iyer, Wojcik and Ditto2013; Gray & Keeney, Reference Gray and Keeney2015), and to infusing it with up-to-date research data. Morality is also exploited and studied in various ways: As an ideological premise and a distinctive difference between conservatives and progressives (Hannikainen et al., Reference Hannikainen, Miller and Cushman2017; Jost et al., Reference Jost, Glaser, Kruglanski and Sulloway2003; Lakoff, Reference Lakoff2010; McAdams et al., Reference McAdams, Albaugh, Farber, Daniels, Logan and Olson2008), as a normative predicate and individual difference (Dunn et al., Reference Dunn, Brown and Maguire1995; Giammarco, Reference Giammarco2016; Luke et al., Reference Luke, Prentice and Fleeson2021; Meindl et al., Reference Meindl, Jayawickreme, Furr and Fleeson2015), and as a main conflict resolution mechanism (Broeders et al., Reference Broeders, den Bos, Müller and Ham2011; DeScioli & Kurzban, Reference DeScioli and Kurzban2013; Opotow, Reference Opotow, Thorkildsen and Walberg2004).

Our research examines moral reasoning as a practical application of the socio-psychological gaze and emphasizes the notion of consistency as an intrinsic operational element of moral reasoning and practices. The study explores the link of ethics to both ideological and worldview concerns (Amable, Reference Amable2011; Cornwell & Higgins, Reference Cornwell and Higgins2013; Hatemi et al., Reference Hatemi, Crabtree and Smith2019; Pyszczynski & Kesebir, Reference Pyszczynski, Kesebir, Shaver and Mikulincer2012) and to norms of distributive justice (Arsenio, Reference Arsenio2015; Folger et al., Reference Folger, Cropanzano, Goldman, Grenberg and Colquitt2013; Sparkes, Reference Sparkes1990). It hypothesizes that ideology and worldview predicate specific moral bundles, which determine the levels of moral absolutism, and predicts the perspective of consistency norm in positive or negative terms and ultimately leads to the adoption of a specific attitude towards distributive criteria.

Ideological and Worldview Perspectives

The ideological-worldview function of the human subject has been widely studied within different traditions of social psychology, including social order and power relations (Duckitt & Fisher, Reference Duckitt and Fisher2003; Jost, Ledgerwood, et al., Reference Jost, Ledgerwood and Hardin2008), perspectives on human nature (Klubertanz, Reference Klubertanz1953; Wrightsman & Wuescher, Reference Wrightsman and Wuescher1974) and competitive world (De Keere, Reference De Keere2020; Perry et al., Reference Perry, Sibley and Duckitt2013). Each of these traditions assumes intrinsic human characteristics and content-specific dispositions and issues. In this sense, and taking into account how the worldview perspective is linked to and mediated by the adoption of ideological attitude systems (Federico et al., Reference Federico, Hunt and Ergun2009; Walsh, Reference Walsh2000), perspectives on social order (Chryssochoou, Reference Chryssochoou2018; Papastamou et al., Reference Papastamou, Prodromitis and Pappas2022), neoliberalism (Bettache & Chiu, Reference Bettache and Chiu2019; Girerd et al., Reference Girerd, Ray, Priolo, Codou and Bonnot2020), perspectives on human nature (Klubertanz, Reference Klubertanz1953; Wrightsman & Wuescher, Reference Wrightsman and Wuescher1974) and competitive world (Duckitt et al., Reference Duckitt, Wagner, du Plessis and Birum2002; Perry et al., Reference Perry, Sibley and Duckitt2013), are tested as organizing principles of ethical reasoning.

Ideology refers to patterns and contents of social order perception and reproduction, directly linked to basic human motivations for understanding the world (Feldman, Reference Feldman, Huddy, Sears and Levy2013; Jost et al., Reference Jost, Federico and Napier2009, Reference Jost, Federico, Napier, Freeden, Sargent and Stears2013). By mixing evaluative judgements with objective descriptions, ideology links individual, social and political views and allows for the avoidance and management of existential threat and the maintenance of important interpersonal relationships (Jost, Reference Jost2017, Reference Jost2019; Jost, Ledgerwood, et al., Reference Jost, Ledgerwood and Hardin2008; Duckitt & Fisher, Reference Duckitt and Fisher2003;). Conceived as a “complex of representations, ready-made ideas, relatively coherent, mixing values and beliefs, but perceived by those who subscribe to it as true and globalized knowledge” (Lipiansky, Reference Lipiansky, Aebischer, Deconchy and Lipiansky1991, p. 359), ideology naturalizes social arbitrariness, transforms values into facts and interest into law (Papastamou, Reference Papastamou2008). Finally, as a set of consensual shared beliefs that provide the moral and intellectual basis for a social, economic, and political system, ideology imbues human existence with meaning and inspiration, reduces, not always as effectively, anxiety, feelings of guilt and shame, dissonance, discomfort, and uncertainty (Chen & Tyler, Reference Chen, Tyler, Lee-Chai and Bargh2001; Jost & Hunyady, Reference Jost and Hunyady2005; Kluegel & Smith, Reference Kluegel and Smith1986).

Neoliberalism as an ideology constitutes both a specific socio-political project and, a system of ideas of anthropological implications with a clear political-cultural imprint (Asen, Reference Asen2017; Bettache & Chiu, Reference Bettache and Chiu2019; Girerd et al., Reference Girerd, Ray, Priolo, Codou and Bonnot2020). It proposes an understanding of the self as a continuous developmental project and the need for personal growth and fulfilment as imperative (Adams et al., Reference Adams, Estrada-Villalta, Sullivan and Markus2019; Beattie, Reference Beattie2019). Neoliberalism, also, presupposes freedom from the constraints of external interventions and posits effectively competitive relationships in the context of minimal state interventions as a common premise (Beattie, Reference Beattie2019). By emphasizing individual freedom, self-expression and personal development (Deleuze & Guattari, Reference Deleuze and Guattari1983) over other liberal values such as equality, it reinforces individualistic psychological tendencies (Adams et al., Reference Adams, Estrada-Villalta, Sullivan and Markus2019; Kashima, Reference Kashima2019) and constitutes a highly attractive context for ambitious individuals (Davies, Reference Davies2016). Rejecting, anything that impedes individual development and expression -even if they are obligations- enhances private initiative and individual economic interest as means and measures of personal well-being and happiness (Adams et al., Reference Adams, Estrada-Villalta, Sullivan and Markus2019; Venugopal, Reference Venugopal2015), and puts at risk the terms of social engagement.

Expressions of neoliberal cultural norms are associated with a wide range of social philosophies and worldviews (Birch, Reference Birch2015; Frodeman et al., Reference Frodeman, Briggle and Holbrook2012; Leone et al., Reference Leone, Giacomantonio and Lauriola2017; Wolford, Reference Wolford2005), such as the Competitive Worldview. Directly related to expertise and the sharing of knowledge among the competent and successful (Duckitt et al., Reference Duckitt, Wagner, du Plessis and Birum2002; Perry et al., Reference Perry, Sibley and Duckitt2013; Sibley et al., Reference Sibley, Wilson and Duckitt2007), the world is described as a highly competitive environment, equivalent to a jungle, where engagement in a ruthless and unethical struggle for resources and power is inevitable and winning is everything (Duckitt et al., Reference Duckitt, Wagner, du Plessis and Birum2002; Federico et al., Reference Federico, Hunt and Ergun2009; Perry et al., Reference Perry, Sibley and Duckitt2013). By insisting on maintaining the intergroup hierarchy and justifying inequality, it attracts people who belong to the conservative, right side of the conventional right-left spectrum (Duckitt, Reference Duckitt2001; Freire, Reference Freire2015) or who have been exposed to social situations of high inequality and competition (Perry et al., Reference Perry, Sibley and Duckitt2013; Radkiewicz & Skarżyńska, Reference Radkiewicz and Skarżyńska2021). As a world view it fosters a belief in the dynamics of domination over the weak, producing a rationale for the more powerful to be paternalistically benevolent towards the less powerful (Duckitt, Reference Duckitt2001; Duckitt & Fisher, Reference Duckitt and Fisher2003).

Since ideology has anthropological foundations, the discourse on human nature is taken together as the dialectical relation of internal consistency-external feedback, which expresses the constitutive activity of the human subject, that is, its ability to negotiate and reflect on its own existence (Jaggar, Reference Jaggar1983; Laird, Reference Laird2014; Wrightsman & Wuescher, Reference Wrightsman and Wuescher1974). According to Wrightsman and Wuescher (Reference Wrightsman and Wuescher1974), the Philosophy of Human Nature (PHN), is the composite of six factors -which can also be considered independent of each other- functions as an existential and interpretative substrate and determines the terms of negotiation between self and “other”. By grouping together, the central thematic reference points, it comes down to two main axes. On the one hand, it describes trustworthiness, altruism, independence, and willpower-rationality, as key regulators of human behavior and a measure of a subject’s attitude and perspectives towards another, and on the other hand, complexity, and variability, as a common core of evaluative nature, related to the understanding and consistency of human nature (Agger et al., Reference Agger, Goldstein and Pearl1961; Maddock & Kenny, Reference Maddock and Kenny1972; Wrightsman, Reference Wrightsman1964). As a world-theoretical dimension of social thought, it recognizes political cynicism, rationalism, lower levels of life satisfaction and less favorable value judgments about self and “others” as the basis for differentiating negative philosophy of human nature from positive philosophy of human nature, which is associated with strong religious feelings, reliability, morality and responsibility, goal-orientation, altruism, and an optimistic view of life (Sanford, Reference Sanford1961; Wrightsman, Reference Wrightsman1964).

Therefore, inter-subjective arrangements emerge as forms of reasoning and understanding of the world and reframe reality in socio-political and anthropological terms.

Morality

Moral foundations theory is a condensing theory that attempts to systematize the problematics of ethical thinking and evaluation (Haidt & Joseph, Reference Haidt and Joseph2004). It proposes that the concept of ethics is regulated through five dimensions of moral foundations (Graham & Haidt, Reference Graham, Haidt, Mikulincer and Shaver2012; Graham et al., Reference Graham, Nosek and Haidt2012):

Harm/care: Relates to values such as compassion, kindness, and caring and refers to a person’s ability to feel -or not feel- another’s pain.

Fairness/cheating: Emphasizes the principle of proportionality, refers to the sense of justice, the assertion of rights and the concept of autonomy.

Loyalty/betrayal: It refers to patriotism, self - sacrifice and vigilance as an obligation to the group.

Authority/Subversion: In the context of obligatory hierarchical social relations, it refers to respect for tradition and obedience to legitimate authority.

Sanctity/degradation: Purity, control of carnal desires, especially lust, and hygiene are posited as key components of man’s effort to live virtuously.

According to moral foundations theory, morality, regulates attitudes towards self and “others” and sensitivity to external/internal feedback. It also determines the terms of negotiation at public and private levels and acts as a balancing factor between disengagement from the constraints of belonging and the qualification of sharing (Haidt & Kesebir, Reference Haidt, Kesebir, Fiske, Gilbert and Lindzey2010; Graham et al., Reference Graham, Haidt, Motyl, Meindl, Iskiwitch, Mooijman, Gray and Graham2018; Graham, Nosek, Haidt, Iyer, Koleva, et al., Reference Graham, Nosek, Haidt, Iyer, Koleva and Ditto2011; Zigon, Reference Zigon2009). Morality legitimates the social order because it facilitates an appreciation of social reality and governs relations of trust (Alexander, Reference Alexander and Jeffries2014; Rawls, Reference Rawls, Hitlin and Vaisey2010).

By examining the moral narrative of liberals and conservatives the differences that systematically appear between them are assessed as predictable and foreseeable (Graham et al., Reference Graham, Haidt and Nosek2009; Haidt & Graham, Reference Haidt and Graham2007; Haidt & Hersh, Reference Haidt and Hersh2001). Specifically, one the one hand, conservatives prime the dimensions of loyalty/betrayal, authority/subversion, and sanctity/degradation. They also strongly resist social change, accept inequality as natural and inevitable, appear as more dogmatic with a stronger death anxiety and choose conflict as a mechanism for restoring order (Graham & Haidt, Reference Graham, Haidt, Mikulincer and Shaver2012; Graham et al., Reference Graham, Haidt and Nosek2009; Haidt & Graham, Reference Haidt and Graham2007; Schein & Gray, Reference Schein and Gray2015; Sherkat & Ellison, Reference Sherkat and Ellison1997). In contrast, liberals consistently demonstrate a preference for explanation and justification since harm/care and fairness/cheating are important to them. They also commit to upholding values such as altruism, justice, and equity in the context of promoting broader social change (Carens, Reference Carens, Barry and Goodin1992; Graham & Haidt, Reference Graham, Haidt, Mikulincer and Shaver2012; Perry & Perry, Reference Perry and Perry2009; Schein & Gray, Reference Schein and Gray2015).

Given conservative thinking generally refers to principles, while progressive perspectives are humanistically oriented, it is reasonable that moral absolutism, as a self-referential sentiment, is directly linked to the bundles of moral foundations. As an inviolable principle independent of content, moral absolutism is bounded and delimited in the qualitative characteristics that individuals attribute to the concept of morality (Peterson et al., Reference Peterson, Smith, Tannenbaum and Shaw2009; Vecina et al., Reference Vecina, Chacón and Pérez-Viejo2016). Moral absolutism violates the terms and conditions of social connectivity because it is derived from epistemological motives of certainty and functions as a predominantly rationalizing mechanism (Haidt & Kesebir, Reference Haidt, Kesebir, Fiske, Gilbert and Lindzey2010; McConnell, Reference McConnell1981; Shaw et al., Reference Shaw, Quezada and Zárate2011). It proposes a model whereby morality is independent of culture and circumstances and posits morals as being dictated by self-interested ends (Graham & Haidt, Reference Graham, Haidt, Mikulincer and Shaver2012; Peterson et al., Reference Peterson, Smith, Tannenbaum and Shaw2009), and that substantive moral behavior is optional (Hawley, Reference Hawley2008; Leone et al., Reference Leone, Giacomantonio and Lauriola2017; Shaw et al., Reference Shaw, Quezada and Zárate2011). Moral absolutism operates as a scheme of thought that either prevents the reduction and matching of morality to its social contexts (Hawley, Reference Hawley2008) or emphasizes the positivity of consistency through the practical service of an ideal, recalls that moral behavior inherently involves patterns of consistency.

Norm of Consistency

Consistency, either as a socio-psychological concept and social value (Festinger, Reference Festinger1957; Heider, Reference Heider1946, Reference Heider and Heider1958; Newcomb, Reference Newcomb1953) or as a constant human demand and natural need, is studied as an ideological norm and a problematic about individual differences. The preference for consistency between beliefs, behaviors and attitudes, at public and private levels (Campus, Reference Campus1974; Caspi & Moffitt, Reference Caspi and Moffitt1993; Nichols & Webster, Reference Nichols and Webster2014; Unsworth & Miller, Reference Unsworth and Miller2021), is operationalized and interpreted, first and foremost as a specific theoretical problematic that presupposes a disposition to classify participants by their main ’personality trait’ of commitment or not to the constancy of words and actions or to the consistency of words and attitudes over time (Fleeson & Noftle, Reference Fleeson and Noftle2008; Papastamou & Prodromitis, Reference Papastamou and Prodromitis2010; Swann & Brooks, Reference Swann and Brooks2012). Low levels of preference for consistency are associated with spontaneous and unpredictable reactions, a preference for constant and rapid change, lower levels of self-esteem and higher levels of depression (Cialdini et al., Reference Cialdini, Trost and Newsom1995; Eriksson & Lindström, Reference Eriksson and Lindström2007; Guadagno & Cialdini, Reference Guadagno and Cialdini2010; Sheldon et al., Reference Sheldon, Ryan, Rawsthorne and Ilardi1997). In contrast, high levels of preference for consistency are associated with an increased need for stability (Eriksson & Lindström, Reference Eriksson and Lindström2007; Koriat & Adiv, Reference Koriat, Adiv, Dunlosky and Tauber2016; Nichols & Webster, Reference Nichols and Webster2014;), especially at the personal level, higher levels of self-control (Suh, Reference Suh, Diener and Suh2000), a reduced need for reassurance from external sources (Crocker & Wolfe, Reference Crocker and Wolfe2001), more intense concern about the appropriateness of the social behavior at hand, and reduced variability of reactions to external feedback (Butler et al., Reference Butler, Hokanson and Flynn1994).

Consistency, on the other hand, operates as an abstract ideological principle, as a double-reading pattern of thought, which provides people with meaning and constitutes the existential ground on which the social self is constructed. It is considered essential to personal and social harmony, provides the primary evidence of maturity and is a prerequisite for security and predictability of human thought and behavior (Papastamou & Prodromitis, Reference Papastamou and Prodromitis2010). According to Papastamou and Prodromitis (Reference Papastamou and Prodromitis2010), consistency is open to multiple readings. The positive perception of consistency norm, as a hyper–normative notion, relates to continuity, reliability and stability and is systematically contrasted with the adverse aspects of dogmatism and intolerance, the negative perception of consistency norm. The positive perception of inconsistency, as an organizational principle inherent to openness as a value and an element of individuality, praises flexibility and adaptability, as opposed to the negative perception of inconsistency, which also forcibly frustrates the expectations of the subjects, underlining the notions of unreliability and abrasiveness.

Given, consistency constitutes the most precious manifestation of human nature, and that the endorsement of immorality, in essence, amounts to the activation of the negative perception of consistency, moral behavior and consistency maintain a strong relationship. When someone is accused of being immoral and ends up being judged as inconsistent, highlights the moral judgments and the individual frames of the consistency norm involved in the process. Therefore, the inclusion and co-examination of consistency as a mediating factor in the relationship between morality and justice is necessary, given that the literature so far -at least explicitly- does not include it.

Distributive Justice Norms

Since the search for strict and objective criteria for evaluating and determining just behavior would overlook the importance of subjective experience, it is acknowledged that norms of justice constitute a socially constructed reality, the dynamics of which shape, maintain and alter people’s evaluations of justice (Bauman & Skitka, Reference Bauman and Skitka2009; Deutsch, Reference Deutsch1983; Folger, Reference Folger1977, Reference Folger2012; Folger et al., Reference Folger, Cropanzano, Goldman, Greenberg and Colquitt2005). Distributive justice norms, as criteria for distributing goods and resources in contexts of organized social interactions, presuppose and are based on worldview principles and constitute the practical realization of ethical assumptions (Arsenio, Reference Arsenio2015; Sparkes, Reference Sparkes1990; Folger et al., Reference Folger, Cropanzano, Goldman, Grenberg and Colquitt2013). The norms respond to different rationales, correspond to political actions, and are reflected as the active contribution to socio-political organization (Miller, Reference Miller and Lamont2017; van Parijs, Reference van Parijs, Goodin, Pettit and Pogge2017). The principle of equity presupposes that the benefit is proportional to the contribution, so negotiations and comparisons between individuals are undertaken based on assessments of pros and cons (Adams, Reference Adams1965; Greenberg & Cohen, Reference Greenberg and Cohen2014), and is prioritized in cases where productivity is the main concern (Arts & Gelissen, Reference Arts and Gelissen2001; Deutsch, Reference Deutsch1975). In terms of social policy, it appears in the discourse of conservative regimes as the basis of social welfare programmes (Ennser-Jedenastik, Reference Ennser-Jedenastik2017). The principle of equality, on the other hand, is based on the formulation and application of conditions that ensure equal treatment of all without exception and regardless of social status, income, contribution or need (Deutsch, Reference Deutsch1975). The application of this principle ensures social harmony and protects against the disruption of interpersonal relationships (Ennser-Jedenastik, Reference Ennser-Jedenastik2017). Finally, the principle of need argues that benefits should be directed -primarily- towards those who are underprivileged (Deutsch, Reference Deutsch1975) and is favored in communities that prioritize individual development and well-being based on income criteria (Arts & Gelissen, Reference Arts and Gelissen2001).

High social status and abundance of goods are associated with a preference for the equity norm according to Ennser-Jedenastik (Reference Ennser-Jedenastik2017), while deprivation and poverty are associated with a preference for the principles of equality and need. Furthermore, values and political ideology influence the choice of distributional criterion (Rasinski, Reference Rasinski1987). Conservatives evaluate the equity norm as more equitable, while progressives prefer the equity principle (Rasinski, Reference Rasinski1987; Skitka & Tetlock, Reference Skitka and Tetlock1992). Previous research has shown that the relationship between ideology and preferences for policies is mediated by the social justice evaluations of an individual (Deutsch, Reference Deutsch1975; Feygina, Reference Feygina2013). In normal circumstances those who contribute less, argue that the norm of equity does not apply, thus claiming a share equal to that of others (Leventhal & Anderson, Reference Leventhal and Anderson1970; Messick & Sentis, Reference Messick and Sentis1979). However, there are instance were given that time and cognitive resource saving considerations are involved in the choice of a sharing norm, individuals who are systematically involved in sharing problems prefer the norm of equality, even if the application of the norm of fairness would allow them to get a larger share (Mikula, Reference Mikula1980).

Welfare chauvinism as an ideological project entirely relevant to criteria and priorities in the distribution of resources and goods, setting cultural-ethnic integration as a measure of identity, needs to be considered although it is not part of the traditional theorizing of distributive justice, (de Koster et al., Reference de Koster, Achterberg and van der Waal2012; Hjorth, Reference Hjorth2016). Welfare chauvinism situates the right to distributism in integration (Careja et al., Reference Careja, Elmelund-Praestekaer, Baggesen Klitgaard and Larsen2016; Kitschelt & McGann, Reference Kitschelt and McGann1995), sets citizenship, nationality, race, religion as a criterion (de Koster et al., Reference de Koster, Achterberg and van der Waal2012; Kootstra, Reference Kootstra2016) and is part of populist radical right narratives, in the context of anti-immigration policies. In terms of intergroup integration, it prioritizes the principle of equality for peers and activates the principle of fairness for different ethnic or national groups (van Oorschot, Reference van Oorschot2006), which is why it is preferred in countries with liberal and conservative welfare regimes (de Koster et al., Reference de Koster, Achterberg and van der Waal2012).

Given that theoretical concepts, such as norms of distributive justice, directly related to social justice and clearly indicative of ideological position and social identity, are translated into applied contexts of real life, it is reasonable to think that morality, emerges as demarcation and valuation of the social.

Present Study

This research explores the mediating role of moral foundations, moral absolutism, and consistency norm, building on the already known relationship between ideological-worldview perspectives and distributive justice norms. Literature so far studies consistency mostly as an individual difference and has not yet shed enough light on the critical role of the consistency norm, as a social value and sociopsychological concept. Likewise, there is a theoretical and research gap regarding the relationship between morality and consistency norm, so we aim to leverage and extend insight on this regard.

We investigate the moral reasoning of ideology through moral absolutism and interpretations of consistency norm. By capturing the different ideological-worldview perspectives, we hypothesize that ideology and worldview predict specific contents of moral reference, which in turn prescribe the level of moral absolutism and consequently the perception of consistency, which ultimately determines the attitude adopted towards the criteria for the distribution of goods.

Method

Participants and Procedure

Three hundred and thirteen (N = 313) questionnaires were collected in March–April 2022 in Greece. A total of 193 women (61.7%), 112 men (35.8%) and 8 gender –selected self– identified (2.6%) responded. Participants were between 18 and 71 years with a mean age of 30.28 years (SD=13.37). Participants completed the questionnaires in Greek, using versions validated in this language and were approached individually by researchers. They were asked to reply to a battery of questions related to various social and political issues, that emerge from time to time in public space, and they were presented with a series of statements and were asked to carefully read them and indicate their level of agreement using a seven-point scale from 1 = Strongly Disagree to 7 = Strongly Agree. Table 1 shows sample items, scale scores reliabilities and Cronbach’s alpha. To evaluate statistical power, we used Monte Carlo power analysis for indirect effects (Schoemann et al., Reference Schoemann, Boulton and Short2017). The analysis indicated that a sample size of 313 participants in a serial mediation design with two mediators afforded 87% power (α = .05).

Table 1. Descriptive Statistics and Correlations among Perceptions of Consistency Norm, Distributive Justice Norms, Progressivism on Morality and Moral Absolutism

Note. *p < .01. **p < .05.

Measures

Baseline Measures

Participants self–reported demographic characteristics (e.g., age, gender).

Political Self–Positioning

Political self-positioning was measured on a 10-point scale ranging from 1 = extreme left to 10 = extreme right. Participants were also given the option to refuse positioning on the scale. After recoding the 10–point scale, five groups of political self–positioning were formed: 1 = Left (1– 4), 3 = Center (5 – 6), 4 = Right (7 – 10), 5 = Refusal.

Unless otherwise all variables were measured using a seven–point Likert scale with higher numbers indicating higher values on a given measure.

Ideology

The instrument (Papastamou et al., Reference Papastamou, Prodromitis and Pappas2022) was consisted of 16 items representing different perspectives on social order: Empathy (single item, “It hurts me when other people suffer"), Relative Deprivation (two items; “I often find it difficult to get the things that I and my family need”, “I am satisfied with my life” [reversed], r = .21, p < .001), Legalization of Power Differences (single item, “In this country, power differences between social groups will never change”), Social Mobility (two items, e.g., “In our society, anyone who tries hard succeeds in the end”, r = .65, p <. 001), Dangerous World (single item, ”At this time in our country, life is unpredictable and dangerous"), Collectivism (single item, “Only together with others in the same position can one strive to improve one’s own”), Reproduction of Social Order (single item, “Even if one is qualified, if one does not come from the upper classes, will not succeed”), Norm of Internality (single item, “I need to feel that I personally determine my own destiny”) and Politicization (five items, e.g., “It has always been important for me to publicly express my political views”, “No matter what I do I cannot influence anything that happens in politics” [reversed]), α = .81). The item “I make sure I never read or listen to the news” was excluded from Politicization index due to reliability reasons.

Competitive Worldview

14 items from Competitive Worldview Scale (Duckitt et al., Reference Duckitt, Wagner, du Plessis and Birum2002) were averaged on a single index (“Jungle”, α = .77), after reversing the initial scores so that high values correspond to a feeling of the world as a highly competitive environment (e.g., “It is better to be loved than feared” [reversed], “Everyone has a right to the benefit of the doubt”, “In life it is more important to have integrity in one’s dealings than to have money and power”).

Neoliberalism

Four dimensions of neoliberalism (Girerd et al., Reference Girerd, Ray, Priolo, Codou and Bonnot2020) were measured: Free Will (e.g., “People should take full responsibility for their bad choices.”, α = .75), Hedonism (e.g., “Life is too short not to enjoy every moment, α = .67), Need for Uniqueness (e.g., ”My choices in life are naturally oriented toward what is original», α = .76) and Perceived Personal Control (e.g., “When I make plans, I’m almost certain that I will accomplish them”, α = .45).

Philosophy of Human Nature (PHN)

Positive Philosophy of Human Nature (α = .73) was measured with eight items from Wrightsman Revised Philosophies of Human Nature scale (Reference Wrightsman1964). Example items include the following: “Treat others as you want to be treated”, ”Most people would lie if they had something to gain from it" [reversed], “Most people would stop and help someone who is stuck with a car”, “Most people claim to be honest and ethical, but few actually prove it at the critical moment” [reversed], “Most people would pull over and help someone who’s stuck with his/her car”.

Consistency Norm

The questionnaire included a series of measures to investigate how participants interpret the different perceptions of the consistency norm (see Papastamou & Prodromitis, Reference Papastamou and Prodromitis2010). A confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted to confirm the associations between the observed variables and the factors. The four-factor model fit the data acceptably: χ2(14, N = 313) = 26.9, p = .02, χ2/df = 1.92, SRMS = .04, CFI = .96, RMSEA = .05 [.02, .085]. The endorsement of each perception was measured with two items: Positive Perception of Consistency (e.g., “To be consistent and stable, one needs one’s actions to always agree with one’s ideas and principles”, r = .28, p < .001), Negative Perception of Consistency (e.g., “When one always behaves according to one’s ideas and opinions, it is a manifestation of rigidity and inability to adapt to the changing world”, r = .52, p < .001), Positive Perception of Inconsistency (e.g., “To behave in a way that does not always agree with one’s ideas shows an ability to be flexible and adapt to circumstances”, r = .36, p < .001) and Negative Perception of Inconsistency (e.g., ”When a person’s actions are not consistent with his previous actions, that person has an unstable personality", r = .18, p = .002). Single index Positive Perception of Consistency was composed by subtracting Negative Perception of Consistency index from the Positive Perception of Consistency index. Likewise, index Positive Perception of Inconsistency was composed.

Progressivism on Morality

The Moral Foundations Questionnaire - Short Version by Graham, Nosek, Haidt, Iyer, Spassena, et al. (Reference Graham, Nosek, Haidt, Iyer, Spassena and Ditto2011) was used. Participants were asked to assess, when deciding if something is right or wrong, whether each of the 11 items is relevant to their way of thinking, using a scale from 1 = Not Relevant at All to 7 = Completely Relevant. They were also asked whether they agreed or disagreed with each of the next 11 items. Harm/care index and fairness/cheating index were averaged on a single index (“Progressivism”, α = .70). Loyalty/betrayal index, authority/subversion index and sanctity/degradation index were also averaged on a single index (“Conservatism”, α = .84). Single index Progressivism on Morality was composed by subtracting Conservatism from Progressivism.

Moral Absolutism

The Moral Absolutism scale (MAS) by Lauriola et al. (Reference Lauriola, Foschi and Marchegiani2015) were used to measure moral absolutism. The instrument was consisted of six items (“Moral Absolutism”, α = .60). Examples: “There is only one appropriate way to think and act morally”, “Right and wrong are not defined in terms of black and white, since there are gradations” [reversed].

Distributive Justice Norms

We asked the participants to indicate the way the Greek Government and European Union’s resources should be distributed. The endorsement of each norm was measured with two items: “Proportionate to each person’s contribution to society” and “Proportionally to the economic contribution of each member-state” (“Equity”, r = .53, p < .001), “Proportionate to the needs of each individual” and “According to the needs of each member–state” (“Need”, r = .71, p < .001), “Equal for all” and “Equally for all member-states” (“Equality, r = .74, p < .001), “Proportionate to one’s national-cultural background” and “Proportionate to their culture” (“Welfare Chauvinism”, r = .53, p < .001).

Results

Analysis Strategy

Participants were grouped based on their ideological and worldview perception, while also identifying the political profile of each of the three resulting groups. In addition, we tested if there were statistically significant differences by ideological-worldview group in terms of the interpretation of the consistency norm, moral reasoning and the factors that should regulate state benefits. Finally, the serial mediating role of morality, moral absolutism, and the consistency norm interpretation in the relationship between ideological-worldview perspectives and norms of distributive justice was examined.

Preliminary Analysis

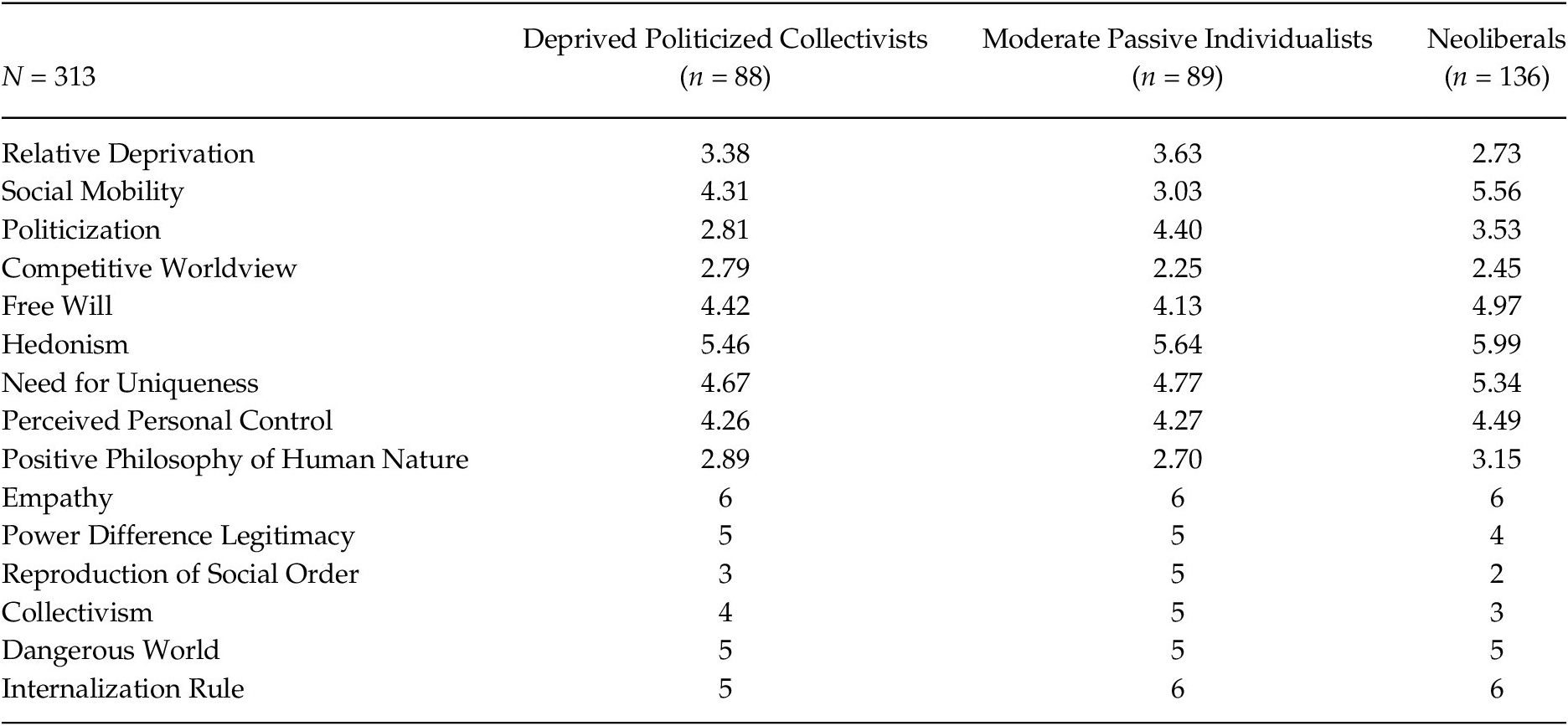

Three groups of respondents were formed after subjecting data on ideology, neoliberalism, competitive worldview, and the philosophy of human nature to K-means Cluster Analysis (see Table 2).

Table 2. Grouping Participants by Ideological - Worldview Perceptions (K-means Clyster Analysis)

Group 1

Moderate Passive Individualists (28.1% of the total sample) express to an intermediate degree, compared to the other two groups, relative deprivation, believe in individual mobility and express the least degree of politicization. They perceive the world as a jungle more in comparison to the other groups, while adopting a relatively positive philosophy about human nature. Their need for uniqueness is not high, and the dimension of hedonism is significantly less preferred than the other groups. They express a neutral attitude towards collective activism, while their “moderately optimistic” view of individual improvability is complemented by their rejection of the social reproduction perspective (individual success due to class origin).

Group 2

Demobilized Collectivists (28.4% of the total sample), believe more than the other groups in the effectiveness of collective action and are more systematically involved in politics. They feel the greatest relative deprivation and assess the possibilities of social mobility as extremely limited. They express, compared to the other groups, the lowest degree of belief in free human will, and seem not to perceive the world as a highly competitive place. In addition, they adopt the least optimistic view of human nature and an intermediate positive attitude towards hedonism. Finally, they are the group that clearly accepts the social reproduction perspective.

Group 3

Neoliberals (43.5% of the total sample) more than any other group, predisposed each one of the four tenets of neo-liberalism (free will, hedonism, perceived personal control, and need for uniqueness). They believe in the possibility of social mobility, systematically avoid involvement in politics and reject the effectiveness of collective action. They do not perceive the world as unfair or antagonistic, and without feeling a sense of relative deprivation, they maintain a relatively optimistic attitude regarding human nature. Finally, they are less likely than other groups to reproduce views on power differentials.

Political Self–Positioning

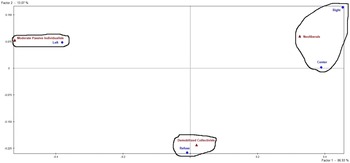

Based on the distribution of ideological-worldview groups on the conventional left-right spectrum, clear differences in their political profile are noted, χ2(6, 313) = 44.18, p < .001. Applying Factorial Correspondence Analysis to a 4 (political groups) x 3 (ideological-worldview groups) table clearly shows that Moderate Passive Individualists are positioned to the left in contrast to Neoliberals who have a clear center-right positioning (see Figure 1). It is the Demobilized Collectivists who mainly refuse to be politically positioned.

Figure 1. Groups of ideological/worldview perspectives and political self – positioning (Factorial Correspondence Analysis)

Analysis

One way analysis of variance showed statistically significant differences between the three groups, F(2, 310) = 3.968, p = .02, on the Positive Perception of Consistency dimension of the Consistency Norm scale (see Table 3). Post hoc analyses using the Bonferroni post hoc criterion for significance indicated that Moderate Passive Individualists (M = .65, SD = 1.87) were more likely to favor the positive perception of consistency norm in comparison to Demobilized Collectivists (M = –.044, SD = 1.66) and Neoliberals (M = .55, SD = 1.88) Statistically significant differences were not observed between the latter two (p = 1).

Table 3. Means, Sstandard Deviations and ANOVA Statistics for Perceptions of Consistency Norm, Distributive Justice Norms, Progressivism on Morality and Moral Absolutism by Ideological- Worldview Group

Note. a,b,c Means that differ in superscripts are significantly different from each other (p <.05) according to the simple main effects analysis.

One-way ANOVA, F(2, 310) = 22.944, p < .001, revealed statistically significant differences between the three groups in relation to the adoption of progressive attitudes to evaluate moral issues while there were no statistically significant differences regarding Moral Absolutism (p = .381) (see Table 3). The Multiple Comparisons Bonferroni Test also revealed that Moderate Passive Individualists (M = 2.35, SD = 1.24) appeared more progressive in their beliefs about morality compared to both Demobilized Collectivists (M = 1. 48, SD = 1.05) as well as with Neoliberals (M = 1.39, SD = .99). No statistically significant differences were observed between Neoliberals and Demobilized Collectivists (p = 1).

Significant differences were observed when studying norms of distributive justice amongst the three groups. Their views differed significantly regarding Equity, F(2, 310) = 9.45, p < .001, and Welfare Chauvinism, F(2, 310) = 9.25, p < .001, (see table 3), but there were no significant differences in their views on Need (p = .167) and Equality (p = .511). The Multiple Comparisons Bonferroni Test revealed differences when it came to rating Equity and Welfare Chauvinism. Equity was less important to Moderate Passive Individualists (M = 2.74, SD = 1.58) than it was to Demobilized Collectivists (M = 3. 34, SD = 1.46) and Neoliberals (M = 3.62, SD = 1.44). No statistically significant differences were observed between Neoliberals and Demobilized Collectivists (p = .508). The Multiple Comparisons Bonferroni Test also revealed that Moderate Passive Individualists (M = 1.68, SD = 1.17) appeared less chauvinist compared to Demobilized Collectivists (M = 2.5, SD = 1.29) and Neoliberals (M = 2.24, SD = 1.36), with no statistically significant differences between the last two (p = .453).

Serial Mediation Model

Serial mediation was conducted using PROCESS Macro (Model 6) for SPSS to test the sequential mediating role of progressivism about morality, moral absolutism, and the positive reading of the consistency norm in the relationship between ideological-worldviews and fairness as one of the four norms of distributive justice. Percentile-based, bias-corrected bootstrap CIs were calculated for the indirect effects using 10,000 bootstrap samples. Participants’ ideological-worldview grouping was set as a predictor variable, progressiveness on morality, moral absolutism and positive perception of the consistency norm were successively set as mediating factors, and equity as a final variable. Helmert coding was chosen for the predictor variable to test the complex mediating mechanism of the difference in equity and welfare chauvinism between the Moderate Passive Individualists and the Demobilized Collectivists and Neoliberal groups, which are not statistically significantly different from each other (see Table 3).

The study assessed the serial mediation with progressiveness on morality, moral absolutism, and positive perceptions of the consistency norm serially mediating the relationship between ideological/worldview perspectives and equity. The results revealed that (see Figure 2), Moderate Passive Individualists are less likely to prioritize the principle of equity than both Demobilized Collectivists and Neoliberals. Moderate Passive Individualists adopted a more progressive attitude towards issues that are subject to moral framing (b = –.91, p < .001) and showed lower levels of moral absolutism (b = –.35, p < .001). They possessed a positive perception of the consistency norm (b = .55, p < .001) and rejected the norm of equity (b = –.11, p < .001; Indirect Effect = –.20, SE = .010, 95% CI [–.044, –.002]).

Figure 2. Results of serial mediation analysis with equity as a final variable (Model 6, Hayes, 2018)

The same test was conducted to check the sequential mediating role of progressivism on morality, moral absolutism, and the positive perception of the consistency norm in the relationship between ideological-worldviews and welfare chauvinism as the final variable. The results (see Figure 3) revealed that Demobilized Collectivists and Neoliberals adopted a less progressive attitude towards moral judgements (b = –.91, p < .001), compared to Moderate Passive Individualist. They had a predilection towards higher levels of moral absolutism (b = –.35, p < .001) and they were more strongly predisposed towards welfare chauvinism, b = .26, p < .001; IE = .008, SE = .014, 95% CI [–.018, –.038]).

Figure 3. Results of serial mediation analysis with welfare chauvinism as a final variable (Model 6, Hayes, 2018)

Discussion

The starting points for our study were the ideological and worldview perspectives and the well-known relationship between morality and distributive justice. Our research has examined the serially mediating role of progressivism about morality, the belief in the sole objectivity of a particular definition of morality and the perception of the consistency norm. The results of our study identified patterns and confirmed our hypothesis that ideology and worldview predict the preference for specific moral reference contents (Amable, Reference Amable2011; Cornwell & Higgins, Reference Cornwell and Higgins2013; Hatemi et al., Reference Hatemi, Crabtree and Smith2019; Pyszczynski & Kesebir, Reference Pyszczynski, Kesebir, Shaver and Mikulincer2012).

Moderate Passive Individualists emerged as the group who adopts the most progressive and inclusive attitude towards moral evaluations and practices (see Progressivism on Morality), while Demobilized Collectivists and Neoliberals maintain a more conservative attitude towards issues that are subjected to moral framing. Moderate Passive Individualists perceive the world as a highly competitive environment, display a potentially dialectical stance and express bona fide humanistic concerns against the discriminatory norms of fairness and chauvinism. They oppose the rationalist reasoning imposed by moral absolutism, acknowledge the positive perspective of the consistency norm, thereby demonstrating in practice their commitment to a genuine and humanistically oriented attitude, and are less predisposed than other groups towards welfare chauvinism and equity.

What is striking is that Collectivists and Neoliberals, identified as apolitical and center-right respectively, end up adopting and invoking common moral reasoning. Demobilized Collectivists, while displaying all those elements that are potentially conducive to a politicized active entity (relative deprivation, collective assertion, high politicization, rejection of the logic of individual mobility), at the same time show adherence to only some elements of the dominant ideology of neoliberalism (cf. hedonism), while rejecting some others, such as the belief in freedom of the will. At the same time they admit the impenetrability of the upper levels of the social hierarchy (reproduction of the social order). In other terms, Collectivists appear to legitimize the system, and at the same time to accept their position within it, thus displaying elements of frustration and ’demobilization’. In this sense, its similarity with the group of Neoliberals could possibly be explained in terms of common moral reasoning.

Consistent with the existing literature remains the finding that morality is predicted by ideology (Amable, Reference Amable2011; Cornwell & Higgins, Reference Cornwell and Higgins2013; Hatemi et al., Reference Hatemi, Crabtree and Smith2019; Pyszczynski & Kesebir, Reference Pyszczynski, Kesebir, Shaver and Mikulincer2012) and worldview (Jensen, Reference Jensen1997) and predicts attitudes toward distributive justice norms (Bauman & Skitka, Reference Bauman and Skitka2009; Skitka et al., Reference Skitka, Bauman, Mullen, Sabbagh and Schmitt2016), thus confirming our hypothesis. Likewise, ideology predicts attitudes toward norms of distributive justice (Arsenio, Reference Arsenio2015; Folger et al., Reference Folger, Cropanzano, Goldman, Grenberg and Colquitt2013; Sparkes, Reference Sparkes1990). Based on the results, Individualists, while maintaining the most progressive attitude towards moral evaluations and practices (Rasinski, Reference Rasinski1987; Skitka & Tetlock, Reference Skitka and Tetlock1992), appear as the least absolute on the issue of defining morality and attribute a positive sign to consistency, invoking the concepts of reliability and stability. When asked to evaluate the criteria for assessing and determining fairness, Individualists do not favor the principle of fairness, and disavow the belief that contribution is initial and ultimate criterion of distribution. Similarly, in the case where welfare chauvinism constitutes the distributive criterion, Individualists again appear as the most progressive and least absolute, rejecting views that ground distributive justice in inclusion and posit cultural and ethnic elements as the measure of selective sensibilities.

To sum up the contribution of the present research, moral absolutism and the reading of the consistency norm emerged as exponents of the adoption of specific moral codes, based on the exploration and mapping of the meaning attributed to the world. In contrast to the previous work, consistency was studied and exploited as socio-psychological concept and social value, rather than as an individual difference. Based on the above, reality seems to be interpreted through the activation of perception schemes regarding social order and human nature. This interpretation affects the attitudes towards morals and implies that morality is a social construct rather than an inherent human characteristic.

The finding that morality should not be inscribed in a single and absolute framework is intriguing and needs to be further shed. The multiple framings and interpretations of the consistency norm constitute evidence for the hypothesis that morality should not be studied and exploited as the super-rule that structures the existence and the meaning-making order of the world.

While we focus on several meaningful antecedents by describing a contextually rich investigation of the moral reasoning of ideology, we are hereby aware of some limitations concerning our research. First, we employed convenience and snowball sampling strategies in this study; this may have contributed to a non-representative sample of the population. Secondly, given that our findings are context–specific, our findings should not be considered as definite. For this reason, the relationship between moral absolutism and the consistency norm needs further examination, as there is evidence of a correlation between the two. Respectively, the relationship between the consistency rule and welfare chauvinism needs to be further examined. Moreover, given the normative and prescriptive role of consistency, future research should investigate its effects on the preference for moral reasoning, particularly when either a positive reading of the consistency or inconsistency becomes salient. Correlational research could also explore the potential moderating role of the consistency norm. Lastly, metaphysical concerns or metrics related to religiosity could possibly be included as worldview parameters.