Portugal had a significant presence in Rome from at least the fourteenth century onwards, evidence of which is the church of Sant'Antonio dei Portoghesi that was established in the fifteenth century on a street perpendicular to what is now the via della Scrofa (D'Almeida Paile, Reference D'Almeida Paile1951; Vasco Rocca and Borghini, Reference Vasco Rocca and Borghini1992; Pereira, Reference Pereira1994). In no other period was that presence stronger than during the reign of King John V (1707–50), as a result of a strategic attempt to give Portugal visibility in European affairs (Martín Marcos, Reference Martín Marcos and Diez del Corral2019). Documentation of important political and religious issues from that period frequently mentions Portuguese personalities, who had great prominence in the social life and festivities of Rome (Vasco Rocca and Borghini, Reference Vasco Rocca and Borghini1995; Diez del Corral, Reference Diez del Corral2019). It is thus of particular interest, for social history, urban and demographic studies, and for art history (from a sociological perspective), to know where the Portuguese were situated in the fabric of the city. Knowledge of these details allows for a reconstruction of important aspects such as the investments made in Portuguese representation, the human and material arrangement of the households of the representatives, and chrono-constructive elements, or architectural history, associated with their residences, among other things.

The more prominent personalities, i.e. ambassadors, envoys and cardinals, are the most interesting figures, and their places of residence are especially relevant for an accurate contextualization of both their missions in Rome, and the impact they had on the city's life. Information about the Joanine ambassadors to Rome is relatively scarce due to the loss of primary sources in the earthquake that devastated Lisbon in 1755. However, thanks to a comparison with Roman sources and a more in-depth study of Portuguese documents (which still need much more attention), it is possible gradually to reconstruct the activity of these agents in the Pontifical court.

In this article we shall focus on the first stages of the special envoy André de Melo e Castro's installation in Rome, from the perspective of the sociology of art. This examination will highlight certain aspects that may seem trivial, such as the difficulty in finding suitable lodgings, or the organization of the serving staff, but which, in fact, influenced the evolution of his mission. We shall also examine the emergence of a network of artists and artisans, which generated a great number of commissions destined for the Portuguese court.

To carry out this study we shall use bookkeeping records detailing the accounts and expenses of the embassy, and we shall employ a method suggested by Renata Ago (Reference Ago2006) which has successfully depicted members of the middle and lower classes of Rome in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Apart from the sources of André de Melo's computisteria, we shall compare data from another contemporary source — a report of the Portuguese envoy's journey to Rome written by his secretary and published in Paris in 1709. This source allows us to see one step ahead and to correlate the expenses with the ceremonial, and with the image of the Portuguese monarchy during Melo's early days in Rome. In terms of the ceremonial and its political implication, this article is based on the works of Antonietta Visceglia (Reference Visceglia2002, Reference Visceglia2010). A study of the costs sustained by the Portuguese envoy sheds light on the problems that ensued when the palace did not follow the norms of etiquette, and the subsequent impact on Melo's appearance in public, that is, his performance. Footnote 2 Another objective of this paper is to identify the growing network of artists who provided part of the commissions that were to be dispatched to Lisbon, as well as works produced for the Portuguese diplomats and agents in Rome.

At the time of the death of Peter II of Portugal in 1706, relations between Portugal and the Holy See had suffered a sudden turn after the Portuguese Crown aligned itself with the Holy Roman Empire in the Spanish War of Succession (Brazão, Reference Brazão1937). With the advent of Phillip V to the Spanish throne in 1701, a conflict arose that put to the test old alliances and balances of power because of the disputed succession of Charles II.

Initially, Peter II chose to remain neutral, given the difficulties of the new Braganza dynasty in being recognized after the Restauração in 1640.Footnote 3 However, in 1703 he signed the Treaty of Lisbon, joining the Great Alliance (formed by the Holy Roman Empire, England and the United Provinces of Holland) against Spain and France. Soon afterwards he signed the Treaty of Methuen, associating himself with England through a series of commercial agreements which certain members of the Portuguese nobility, such as the influential D. Luis da Cunha, saw as an act of submission.

The suddenness of this change in coalition partners, which turned Portugal into the operational base of the Great Alliance, was in part due to strategic interests, but unquestionably Peter II was seeking more prominence for Portugal in European politics. Despite the alleged advantages for Portugal of this new foreign policy, the king had to justify to his subjects his change of alliances, a new policy that was also recorded in writing.Footnote 4 His son, John V, maintained this alliance, and had the same objective — to focus the attention of his overseas empire on European affairs.

This is the context in which, after the death of King Peter II in December 1706, the new king, John V, took the decision to relieve Father Antonio Rego of his post as the representative of Portugal in Rome, and to initiate a period of renovation in diplomatic representation. He would thus fulfil his ambitions for a stronger Portuguese presence in the political milieu of Rome. The young king sought out individuals with secular profiles and intellectual educations, frequently linked to the Republic of Letters. In 1707 he appointed as special envoy to the Pontifical city André de Melo e Castro, count of Galveias (1668–1753) and the second son of Dinís de Melo e Castro, King Peter II's former councillor of state and of war. A good deal of information about his mission has been preserved, but unfortunately very little is known about his daily social life during his long stay in Rome. His assignment in Rome ended (abruptly) in 1728 when the Bichi affair led to a diplomatic rift and all Portuguese subjects in Rome were obliged to return to Lisbon (Martín Marcos, Reference Martín Marcos and Diez del Corral2019: 35–40).

As a young man Melo had received an ecclesiastical education, but he soon abandoned religious life and embarked on a brilliant diplomatic career at the time of the Spanish War of Succession (Brazão, Reference Brazão1937: 2). According to Caetano de Sousa (Reference Caetano de Sousa1735: 698), Melo had already served under Peter II as envoy to Rome before being assigned for the mission by John V, and this had earned him the respect of the young Braganza monarch. However, none of this is apparent in John V's instructions to Melo in 1707, recorded by Brazão (Reference Brazão1937: 5–22). Although Sousa's hypothesis cannot be completely dismissed, the truth of the matter is that the instructions reveal no indication that Melo was familiar with the Roman court because those directives inform him of the procedures and mores to be followed upon his arrival in Rome. In the political sphere Melo was requested, among other things, to deal with the abuses of the Apostolic datary, the incessantly complex padroado real (royal patronage) in the Orient and the Chinese rites controversy (Ramos, Reference Ramos and De1991). André de Melo is also advised to support firmly the cause of the Habsburgs and the archduke Charles III as legitimate heir to the Spanish throne — an indication that John V was fully signed up to the shift in international relations initiated by his father.

The most complete and contemporaneous extant source for the mission of André de Melo is the above-mentioned report, or relation, written in French and Portuguese by Melo's secretary De Bellebat, entitled Relation du voyage de Monseigneur André de Melo de Castro à la cour de Rome. De Bellebat's splendid work was published in 1709 in Paris, and included large engravings by Pietro Lerman and Giovanni Battista Sintes (1680–1760) illustrating, among other things, the sumptuous carriages that the Portuguese envoy used in Rome. De Bellebat records all the stages of Melo's journey to Rome, including visits to various cities. He also depicts Melo's first period in Rome, the ceremonial problems that arose and the preparation of the carriages for his public presentation. The nature of the publication, and the fact that it was written in two languages, is an eloquent manifestation of both the importance attributed to Melo's mission, and the desire to project from Rome a strong image of the Portuguese monarchy to the rest of the courts in Europe.Footnote 5

Melo departed from Lisbon in October 1707 and arrived in Rome in early December. His formal entrance was postponed until April 1709, presumably for ceremonial reasons, as there was no established etiquette yet for special envoys. At the time (six years after the outbreak of the Spanish War of Succession), Rome was sharply divided between two groups: on one side there were the followers of Phillip V (the French and Spanish gallispani), and on the other side there were those in favour of the Habsburg Empire and the Archduke Charles, Portugal among them. What elsewhere would probably have led to armed conflict led in Rome to a confrontation of a more visual nature. This ‘war’ of etiquette was manifested in the numerous ceremonial displays performed by the supporters of each side.Footnote 6 In this sense, the arrival of the Portuguese envoy and the outwardly trivial conundrum that ensued incites deeper reflection; it not only provides information about Melo's residences and his network of artists, but it also reveals the importance of ceremonial at a time when any action and/or omission was called into question in that theatre of nations which was Rome.

1. ARRIVAL IN THE PONTIFICAL CITY AND SELECTION OF A RESIDENCE

Until recently, only two residences in Rome were known for Melo: the Cavallerini palace situated in the via Barbieri, adjacent to the area of the present-day Torre Argentina, and the Cesarini palace, located in the present-day Largo di Torre Argentina.Footnote 7 Both are mentioned in secondary sources as being the diplomatic headquarters of André de Melo, and to this day an analysis is still pending of their role in Portugal's political life and in the urban fabric of Rome. However, there was, in fact, a third residence, which was the headquarters of Melo's legation when he first arrived in Rome. This residence shows some of the challenges of accommodating the floating population in Rome at this time.

With the exception of Spain's Palazzo de SpagnaFootnote 8 (initially rented, and later purchased), which early on became the permanent headquarters of the Spanish ambassadors (Anselmi, Reference Anselmi2001), it was customary for the representatives of the different countries in Rome to look for a residence to rent. They would adapt the residence to their needs, and once their mission was complete, it would return to the real estate market. This situation, which may seem insignificant, actually caused considerable inconvenience to the diplomats, who usually arrived with large retinues, making it hard to find a suitable and large enough palace to rent in the city.Footnote 9 The expense records (Computisteria and Spese) of André de Melo's embassy currently preserved in the archives of the Biblioteca do Palácio Nacional de Ajuda in Lisbon, reveal that the first residence of the envoy was in the (no longer extant) Buratti palace, also called Palazzo Alberoni, in the via del Angelo Custode. This street and all of its buildings were demolished in 1927 when that area of the city underwent re-urbanization to make way for the present-day via del Tritone.

The Buratti palace was in the middle section of the street and occupied quite a large plot, judging by Nolli's plan of 1748 (Fig. 1), which shows two large patios (Delsere, Reference Delsere, Benedetti and Accorsi2012: 39 n. 142). This property belonged to the parish of Sant'Andrea delle Fratte, abutted the former church of the Custodian Angel, and was one plot further in the direction of the Barberini square (Menichella, Reference Menichella1981: 32).Footnote 10 The palace (which is not mentioned in the few published papers devoted to the topic of John V's ambassadors) was indeed André de Melo's first official residence in Rome.Footnote 11

Fig. 1. Detail from Nolli's plan (1748).

In his Relation, De Bellebat describes in detail the preparations for Melo's arrival in Rome. The Portuguese envoy stopped for a time in Florence where he stayed in the court of the grand duke and took the opportunity to visit the most beautiful parts of that city, though he had to cut short his visit due to the severity of the winter (De Bellebat, Reference Bellebat1709: 21). From Florence he ordered De Bellebat to go on ahead to Rome to find suitable accommodation. It appears that the Frenchman stayed at the house of João Ribeyro de Miranda, a Portuguese compatriot of Melo's who later was integrated into Melo's household as his gentleman of embassies. Ribeyro de Miranda was unable to find a suitable palace at such short notice, so he decided to house the king's envoy and his retinue in the ‘palace of the Priests of St. Bernard’ where they apparently spent fifteen days in great comfort (De Bellebat, Reference Bellebat1709: 22).

A thorough study of Valesio's diaries (1978: III, 926) reveals further data about the location of the Ribeyro house and the circumstances of Melo's arrival in Rome on Saturday 10 December 1707: ‘alle 22 hore giunse in Roma don Andrea Mellos, nuovo inviato del re di Portogallo, con non molta familia et andò alloggiare nella casa del suo agente, che abita nelle case nuove de’ padri di S. Croce in Gerusalemme nella strada che da Piazza di Sciarra conduce alla fontana di Trevi’.Footnote 12 Ribeyro's residence was situated in what is currently the via delle Muratte, a street that runs perpendicular to the Corso. Although the information indicates that the envoy's family was not very large, the house of his agent must not, in reality, have been comfortable or adequate for Melo, which explains the haste in finding a more satisfactory space that would be available no later than 20 December, if we heed the words of Valesio: ‘Sospendi di mettersi in publico questo inviato di Portogallo, il quale habita nel palazzo Buratti appresso l'Angelo Custode, per differenza di trattamento, richiedendolo maggiore di quello si costumi con gli inviati’ (Valesio, Reference Valesio1978: III, 930).Footnote 13

Despite the difficulties, both the selection of a palace and the negotiations for its lease were a very rapid affair,Footnote 14 enabling Melo to focus on other issues, such as the one mentioned by Valesio: a request for new and appropriate protocol of treatment and priorities in consonance with his dignity as special envoy (De Bellebat, Reference Bellebat1709: 23).

Although the Buratti palace was demolished, enough details are known about it to allow for an approximate reconstruction of its appearance. It dated to the sixteenth century and was known as the Lana–Buratti palace and later on the Alberoni palace. An old photograph of the street taken in 1862,Footnote 15 with the church of the Custodian Angel in the foreground, shows a clean façade with nine bays and two entrances, corresponding to its possible division into two large apartments, each with its own patio, either for use by two members of the same family, or for rental, as was the practice with other Roman palaces of that period. At the turn of the eighteenth century, this property was owned by Monsignor Marco Antonio Buratti, deacon of the Congregazione del Buon Governo.Footnote 16 At least one architectural feature from this period is known: a balcony and one of the entrances, of which a partial plan has been preserved (commissioned for building-permit purposes).Footnote 17

In 1725 the Buratti palace was bought by Cardinal Alberoni for 16,600 ecus (scudi). Alberoni's interest in the building derived from its location, for he habitually stayed in a palace across from it.Footnote 18 Alberoni carried out restoration works, expanding the residence and adapting it to his taste. He also bought several other plots of land, though the most striking achievement at the time was a commission of several frescoes from the painter Gian Paolo Pannini.Footnote 19

André de Melo leased the palace from Monsignor Buratti's nephew, the marquis Gregorio Buratti, as demonstrated by the record of payments (Biblioteca de Ajuda (BA), 49-VI-14). The lease was 600 ecus paid every trimester, and seems to be in line with contemporary prices, since an apartment of one storey with a bottega cost approximately 50 ecus per month (Curcio, Reference Curcio and Curcio1987: 135–55). Unfortunately, the parish censuses or the Status Animarum (parish family books) for 1708 confirm the presence of André de Melo but do not list any names of the members of his household, even though spaces had been left for that purpose. However, this omission perhaps conceals some important information that would allow us to estimate the approximate number of rooms in the Buratti palace occupied by the Portuguese mission. According to censuses of the following years, the marquis of Buratti and his family (consisting of his son Giulio and his wife Maria Ippolita) occupied the apartment of the Portuguese envoy.Footnote 20

Renting out family palaces had been common practice in Rome since the late sixteenth century; there was great demand for housing by Rome's temporary population, and an increasing need for cash on the part of the proprietors. Many members of the nobility and the aristocracy preferred to receive income from rents rather than actually to live in their family palaces, and they would frequently retire to other, often more modest houses. It is estimated that by the end of the seventeenth century only 50 per cent of the nobility (in Rome) owned palaces, which demonstrates the dynamism of the real estate market in that city (Cola, Reference Cola and Feingenbaum2014: 46–7). In the eighteenth century this phenomenon led to the construction of pre-designed palaces that could be rented out as profitably as possible, but maintaining the same model of apartment developed in the previous century.Footnote 21

Despite being a sixteenth-century structure, the Buratti palace apparently fulfilled Melo's requirements. However, judging from the short duration of his stay there (he moved out one year later), it proved less than entirely satisfactory. During the year that Melo and his court resided in the via del Angelo Custode, a number of works were carried out to enhance both the living quarters and the exterior of the palace.Footnote 22 At that time the corps of staff, servants and craftsmen who would become part of Melo's inner circle was also beginning to take shape.

Initially everything seemed to indicate that the Buratti palace would be the permanent headquarters of the Portuguese legation during Melo's mission; however, after great expenditure to refurbish the building, in the end another palace was rented near the Torre Argentina. The exact reasons for this move are not known, but the decision most certainly had to do with the location of this second palace, which gave the Portuguese Crown more prominence. Other reasons, such as space and the condition of the building, cannot be ruled out.

2. THE FORMATION OF THE MELO HOUSEHOLD

A piecing together of the famiglia Footnote 23 or household of Melo — the people who were permanently at his service — provides information about how the Portuguese envoy developed his mission in Rome. On the one hand, the size of a famiglia was an unequivocal indication of the degree of financial investment in a diplomatic mission, and on the other hand, it throws light upon the structure and internal management of the palace. Once again, De Bellebat (Reference Bellebat1709: 27) provides invaluable information about the members of the Melo household, data which the parish census had omitted. De Bellebat mentions seventeen members: José Bartole, master of the bedchamber (mestre de camera); Manoel Martins Cansado, secretary; Pedro Vas Tarouco, majordomo (mordomo); João Ribeyro de Miranda, gentleman of embassies (Gentilhome das Embaxadas); Manoel Gonçalves Ribero, Manoel da Fonseca, Sebastián Raposo and Alexandre Herinques, gentlemen attendants (Gentilhomes de Sua Excelencia); the chaplain, Pedro Furtado (capelam); Italian-language secretary, Domenico Antonio Nicolai (Secretario de lingua italiana); two abbots in Melo's service (Abbades de Sua Excelencia), Christovão Pereira and João Dias da Sylva; Maestro di Casa Andrea Napolioni; Melo's tutors (Aios de Sua Excelencia), Amaro da Mota and João de Luca; Monsignor D'Angelis, master of stables (Mestre de estrevaria); Francesco Benincasa, captain of the gate (Capitam da porta); and De Bellebat himself, Melo's footman and secretary (Escribeiro).

Apart from the agent Ribeyro de Miranda, who was already established in Rome when Melo arrived, we can conclude that all the staff members with Italian names were assimilated into the family, as was the case of Andrea Napolioni, who would remain Melo's Maestro di Casa until his departure in 1728. Almost nothing is known about the household members who came from Portugal, although we can presume that Melo was accompanied by gentlemen and some servants of his confidence, such as his tutors.Footnote 24 In addition to the gentlemen, servants and footmen he had a credenziere, Giovanni Tusca, and a deacon of the footmen.

This copious group of servants did not all necessarily reside in the palace with their master; only those who had direct responsibilities to Melo or his possessions did so. When space was limited, it was common for princes and lords to rent small apartments in the vicinity of their palaces to house members of their household. Some even lived in their own homes and commuted every day to work. A paradigmatic example is that of Prince Taddeo Barberini who in the 1630s was obliged to rent twenty houses in the surrounding area of his newly inaugurated Palazzo alle Quattro Fontane, having underestimated the space required for the 125 members of his household (Waddy, Reference Waddy1990: 43).

The specialization of services in households during the last decades of the seventeenth and early eighteenth century tended toward simplification, with one person occupying different positions, which greatly reduced costs. However, in Melo's case, there was a clear separation of tasks among his staff, reminiscent of the structures habitually used by princes in the previous century.Footnote 25 This investment in his personal staff, as well as that of the palace, reveals the importance given to King John V's representation in Rome in those early days, (even though through Valesio we learn that the Portuguese envoy had travelled with a small retinue, which in principle did not involve many staff).

Little is known about Melo's direct family. He had one son, Francisco de Melo, born out of wedlock in 1702. Melo eventually recognized him, and Francisco later became governor of Mazagan and of Mozambique. There are no records of André de Melo e Castro ever marrying, and everything indicates that throughout his mission as special envoy to Rome he remained unmarried. However, a closer analysis of the accounts in Rome reveals the following expense: ‘dispensa del do. [detto] Ecc. [Eccelentissimo] Sr. D. Antonio de Mello e Castro = escudi dodici e baiochi 70 per il brevi ingrediendi per l'Eccelentissima Signora sorella di Sua Ecc. [Eccellenza] = escudi otto per una libra di caccionde che servi per mandare a Donna Bernardina Albani che in tutto fanno come dalla nota 3’ (BA, 49-VI-14, fol. 16).Footnote 26

The aforementioned Antonio was not listed by De Bellebat as a member of the household, which demonstrates that the secretary left the names of direct family members out of his Relation. De Bellebat's priority was to highlight the opulence of the mission (an indication of which was the large number of staff), and not necessarily the presence of family members.

It is possible that Antonio de Melo was the Portuguese envoy's young nephew, born in 1689, son of André's brother Pedro and of Isabel of Bourbon, and who inherited the title of count of Galveias. The reason that he travelled with his uncle was probably to further his education, a practice with precedents, such as the case of Antonio Giuseppe del Giudice Pappagoda, the Italian envoy to Bavaria and later ambassador to France (1715–18): Antonio Giuseppe's father, Domenico del Giudice, and his uncle, the cardinal Francesco del Giudice, were both ambassadors. Antonio Giuseppe accompanied his uncle during his embassy to France, and through the latter's mediation he too was appointed ambassador to France on 18 February 1715.Footnote 27 It is therefore not surprising that André de Melo incorporated his nephew into his entourage. This would give him the opportunity to complete his education in accordance with his rank, particularly if Melo assumed that he was not going to have legitimate descendants. This practice was quite widespread among diplomats, and did not always involve direct relatives.

Antonio's participation in palace life and in the life of the Roman court is a matter that requires more study, but suffice it to point out that his presence was registered in the famous carnival masquerade of 1710, ‘Il trionfo della Bellezza’, in which he was one of the central characters. As Valesio recorded (1978: IV, 390), ‘erano il condestabile Colonna, il fratello del prencipe di Carbognano Colonna, il conte Bolognetti, il marchese Buongiovanni, un nepote dell'inviato de Portogallo, Angelo Granelli genovese e Don Antonio Colonna’.Footnote 28 All the participants in the masquerade paraded on the Corso on horseback wearing lavish attire. They were surrounded by attendants with flamboyant insignias and they escorted a sumptuous carriage carrying the duchess de Segni Cesarini,Footnote 29 who impersonated Beauty, and the prince Alejandro SobieskiFootnote 30 as Courage.

In the aforementioned annotation in the book of accounts there is also a reference to a sister of His Excellency: ‘per il brevi ingrediendi per l'Eccelentissima Signora sorella di Sua Ecc. [Eccellenza]’ (BA, 49-VI-14, fol. 16).Footnote 31 The identification of this character is much more complex because there are no further details; it could refer to María Lobo da Silveira, Melo's oldest sister (born in 1649), or to a younger sister María Josefa de Melo Corte-Real, born around 1660. At this point in the research no more can be advanced about the identity of the ‘sorella dell'inviato’ and this reference raises doubts about whether the (papal) brief was an order from Lisbon for one of Melo's sisters, or if it was the first known allusion to the presence of a woman in the family in the palace.

The company of his sister would have complied with certain norms of etiquette in Roman society, and would undoubtedly have had advantages for the unmarried Melo. A female presence was very important in diplomatic affairs; secular men normally had their wives to help carry out the ritual of visits, whereas cardinals usually resorted to a female family member (Waddy, Reference Waddy1990: 26). In any case, these are the only references to any direct family members of the envoy, and further research will certainly reveal more data about how they participated in Melo's mission.

3. DECORATION AND MAINTENANCE COSTS OF THE PALACE

Important information can be obtained by examining data on the remuneration of workmen including masons, carpenters, painters, locksmiths and glaziers in account books. Among these many paymentsFootnote 32 we find a category that can be designated as decoration and furnishing expenses associated with the residence. There are many receipts that demonstrate the intense activity that took place in the palace during the first months, when all kinds of goods and services were necessary, from the acquisition of furniture, such as the two small alabaster tables ‘con suoi piedi intagliati e tutti indorati’ (‘with carved and gilded legs’) attributed to Egidio Paceri, to the numerous purchases of cloth for liveries and other clothing as well as for wall ornamentation and upholstering (especially for portieras, a kind of backcloth over the doors that could be raised, left at half height, or lowered all the way, according to the degree of privacy desired in a room (Waddy, Reference Waddy1990: 5)). The name of Diodato da Modena, a Jew who specialized in such purchases, appears on several occasions. In 1708 he is remunerated for two red portiere with embroidery, as well as for a piece of white satin for details of the king's arms for the portiere and the canopy.

Among many other invoices, one for an order of red damask for a baldachin is particularly important and worthy of further explanation. Baldachins were placed in the audience rooms and were an indication of the rank of the head of a household, an honour reserved for a privileged few (Bodart, Reference Bodart, Colomer and Brown2003). It is thus plausible that this perquisite was part of the extra privileges granted by the pope in the ceremonial that Melo demanded as soon as he arrived in Rome. Understandably, the moment he learnt that he had been granted it, he immediately took charge of the construction of his own baldachin with the arms of the king of Portugal. It was with good reason that this piece of furnishing was the most eloquent manifestation of his newly obtained rank: it distinguished Melo from the status of resident and positioned him just beneath the ambassador.Footnote 33

The payments for the materials for the baldachin are from May 1708; even without considering the usual delay in the remuneration of artisans and merchants, it is evident that by that time the ad hoc ceremonial for Melo's solemn entrance had been approved. However, the entrance did not actually take place until the spring of 1709, a considerable delay, probably explicable in different ways that cannot be addressed with the necessary thoroughness in this paper. However, it is worth pointing out that political reasons were not the only cause of delay, as proven by studying the expense annotations in the books of the embassy. Those payments show that the envoy's new status entailed a series of ‘improvements’ — additional lavish expenses may have been an important element in delaying the entrance ceremony, and are a factor that historians normally overlook. Moreover, preparations for the cortège of carriages could take months, especially if the diplomat in question had not expedited procedures sufficiently far in advance. This is one of many examples of apparently unimportant expenses revealing that there were more complications and unknown details than meet the eye: besides the valuable information on etiquette and status, these payments also provide another plausible, non-political cause for a delay in the public entrance, as well as more precise post quem data about the approval of the special ceremonial.

On 26 June 1708, De Bellebat was refunded for the purchase of a small walnut table for Melo's office. Other pieces of furniture in exotic wood are also mentioned, such as a small engraved table in white wood by the cabinetmaker Pietro Otti,Footnote 34 and a receipt for the gilder Giovanni D'Angelis who was in charge of decorating six Indian chairs with imitation lapis lazuli.Footnote 35

Regarding other aspects of the palace decoration, Diodato de Modena appears again offering a service: the rental of decorative elements, furniture and especially fabrics for room furnishings was a common practice among the temporary inhabitants of Rome. In Melo's case, Diodato rents him white and green taffeta for the walls of his bedroom.Footnote 36 At the turn of the eighteenth century the Roman nobility's increasing need for cash had led to a proliferation of palaces for rent, and the custom of renting other furnishings to adorn the palace became widespread. Thus, the services offered by Diodato de Modena were also used extensively by members of the nobility (Cola, Reference Cola and Feingenbaum2014).

All these payments were entered in the majordomo's book, though not all acquisitions were handled directly by him; as seen above, Melo's secretary, De Bellebat, received payment for a small table, but more frequently found are payments to João Ribeyro de Miranda, even large sums, such as a (papal) brief for the king's senior chaplain for the amount of 360 escudos to João Pinto Pereira.Footnote 37

The numerous receipts for work on the carriages for Melo's public presentation deserve special mention; these range from metal elements by Domenico Valle, the ottonaro, to various works of embroidery by Marta de Vechii, Caterina Mambor and Francesco Gabrielli, upholstery by the sellaro Antonio Salci, trimming and ornaments by Giovanni Gabriel Mambor, paintings by Luigi de Maigre and Cristoforo Verdene, cabinetmaking by Giuseppe Dalmassi and gilding by Giovanni Battista Gini, among many other artisans who helped create these magnificent pieces.

A recurrent name in the receipts in those early days was that of the goldsmith Duarte Nunes, the only Portuguese artist associated with the Portuguese envoy at that point. Duarte Nunes was registered in the guild of Roman goldsmiths as Odoardo Nunez in 1697 when he obtained his licence to open a workshop in Rome (Vale, Reference Vale2011). Nunes received commissions for numerous pieces, some of which, like a cage and chain for a parrot, show the opulence and extravagance of the interior decoration of the Buratti palace. Nunes also made pieces to adorn Melo's office which were probably in his private quarters.

On 27 May 1708 Nunes was remunerated for a gold medal (whereabouts unknown), which was intended as a present for the French designer of one of Melo's carriages. De Bellebat (Reference Bellebat1709: 29) was in charge of buying this medal, so he probably coordinated the details with Nunes (who had also been the intermediary in the acquisition of the small walnut table mentioned above). De Bellebat claims that Melo had assigned him this task in recognition of his good taste — he had chosen several drawings by the Frenchman for the design of the carriage, which in De Bellebat's opinion brought together the Roman and French styles and had been well received by his master. Until now little was known about the medal other than that it was intended as a gift to the above-mentioned carriage designer, but by matching De Bellebat's Relation with the payments of the household, the author of the medal can be accurately identified as Duarte Nunes. A few days later, on 6 June 1708, Nunes also received payment for two coasters and a candleholder to adorn Melo's credenza.Footnote 38

As well as Nunes, Melo engaged the services of the silversmith Filippo Simonetti to make two large silver candelabras bearing his coat of arms, which was also displayed on the candle-snuffer that came with them,Footnote 39 but about which we have no further concrete data.

Other pieces that appear frequently are porcelain dinner services, which served routinely as gifts in diplomatic circles (Cassidy-Geiger, Reference Cassidy-Geiger2007; Borello, Reference Borello2015). The Portuguese had direct access to the centres of production of ceramics and porcelain in the Orient, a commodity that had become almost a symbol of Portuguese identity (Castro, Reference Castro1987; Guo and Min, Reference Guo and Min2022). Among the various receipts for coffee services and cups with saucers, there are sometimes references to porcelain from Japan. Antonio Pericoli appears to be a habitual supplier, for example, of ‘una tazza di porcellana con suo piatto, per sei chiechere, e sei piattini di porcellana del Giappone’.Footnote 40 Months earlier, in June 1708, Pericoli passes an invoice to Melo's majordomo for a service of eight porcelain cups, a present for Bernardina Albani, a sister-in-law of Pope Clement XI. Melo's household seems to have had a close connection with this woman from the early months of his arrival in Rome; in February a payment is made for ‘escudi otto per una libra di caccionde che servi per mandare a Donna Bernardina Albani’.Footnote 41 ‘Caccionde’ was a medicinal remedy against dysentery, which suggests that there was regular contact with Signora Albani.

Bernardina Albani was the wife of Orazio Albani, the pope's brother, and one of their sons later became a famous patron of the arts, Cardinal Alessandro Albani. Bernardina was a figure in the courtly life in Rome, and was also involved in the Arcadian milieu. Giovanni Crescimbeni dedicated his work L'Arcadia (Rome) to her in 1708. Her connection with the Arcadian Academy is worth noting since the presence and active participation of Portuguese diplomacy therein would be very significant in the following years. So much so, that King John V became an Arcadian in 1721, and Melo in 1723. The Portuguese monarch would also subsidize the Bosco Parrasio, the meeting place for the Academy, and its renovation was commissioned to Antonio Canevari. The presence of a figure such as Signora Albani in the newly initiated social life of the count of Galveias clearly shows that his strategy was to gain the favour of the pope and thereby play a prestigious role in the social networks of Rome.Footnote 42

4. THE ARTISTS OF MELO'S CIRCLE

One of the most complex and fascinating aspects of the Portuguese presence in Rome during the reign of John V was the continuous and extravagant investment in art that took place, not only for the sake of diplomatic representation, but also in the form of numerous commissions to send back to the Portuguese court. This enterprise was directed from Lisbon, but was mostly influenced by the tastes of the men in the king's trust and his agents in the various European courts. Rome unquestionably had the most importance, both in terms of expenditure and the magnitude of the commissions; this reached its zenith with a group of sculptures for the monastery in Mafra in the 1730s (Vale, Reference Vale2002; Haist, Reference Haist2015, Reference Haist and Diez del Corral2019) and the lavish chapel of St John in the church of San Roque (Lisbon) in the 1740s, which was sent by ship, piece by piece, to Lisbon (Vale, Reference Vale2015). That is why it is particularly interesting to trace the origin of the network of artists and artisans who worked directly for Portugal, especially at such an early stage in King John V's reign.

Unfortunately, embassy account books are not usually the best sources of information. Commissions were often conducted by members of the household through intermediaries, and were not always recorded in the ordinary accounts since they were considered extraordinary expenses (Gozzano, Reference Gozzano2015: 34). Curiously, in the case of André de Melo we have enough examples to establish some certainties about the names (of artists) who would later come to be associated with the Portuguese world, but whose first commissions were the work of this special envoy. Thus, it was important to reinforce Melo's status with the creation of a network of artists during his first months in the city.

One of the first problems that emerged in Melo's mission, apart from the search for suitable accommodation, was the aforesaid lack of standard protocol for formal relations with the Roman court. This would partially explain why he remained anonymous for over a year. The triumphal entrance, which he prepared with so much detail, only occurred in April 1709, despite his first audience with Pope Clement XI having taken place in April 1708. As mentioned previously, the records show constant movement during his first months in the Buratti palace, and huge expenditure. While the ceremonial model was being organized in accordance with Melo's criteria, the first essential works of art were commissioned to adorn the diplomatic headquarters with a minimum of decorum.

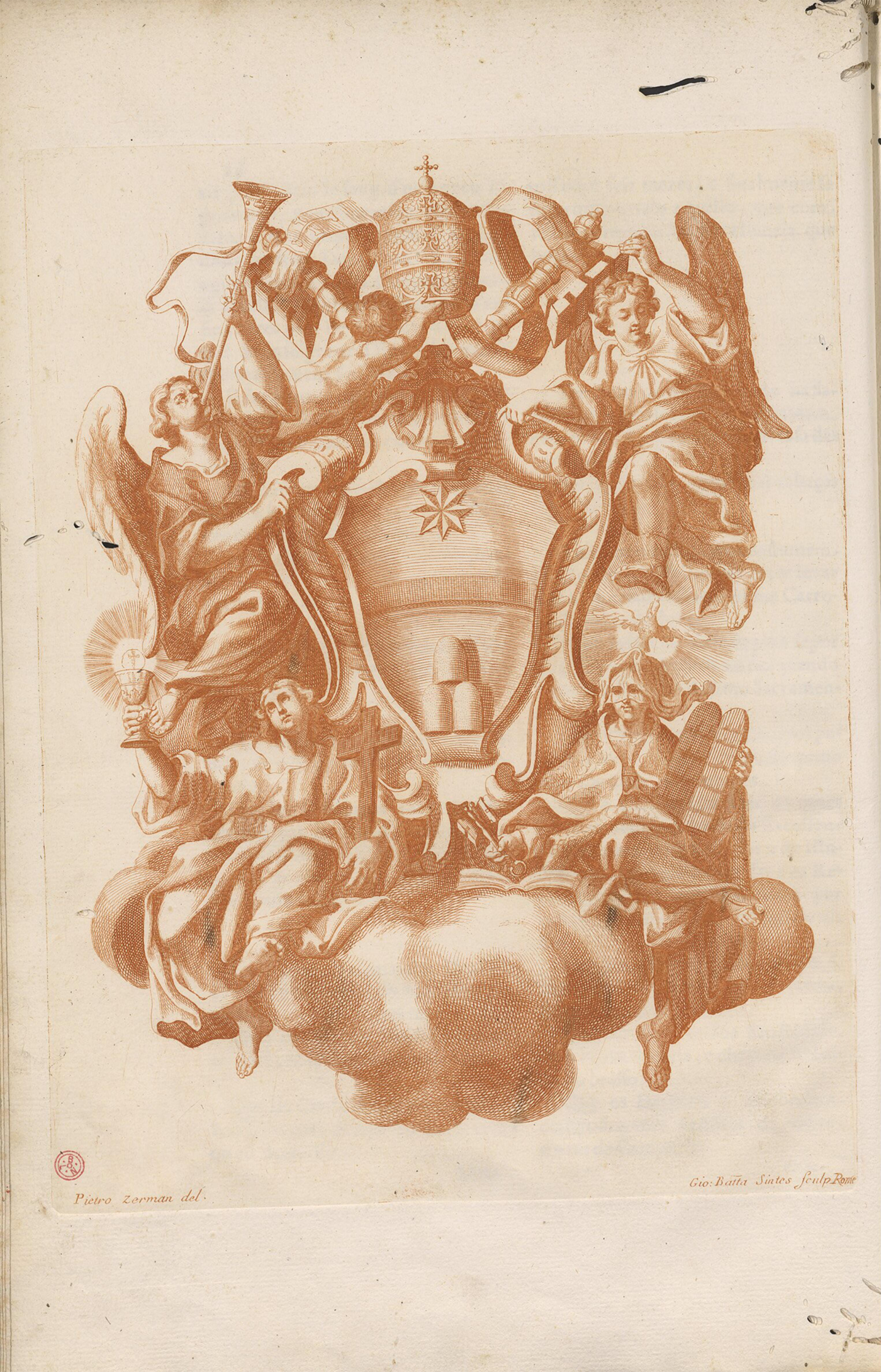

As De Bellebat (Reference Bellebat1709: 25) documents, the coats of arms of the Portuguese king and of the pope were ordered at a very early stage of Melo's mission in Rome so that, like those of all foreign delegations, they could be hung on the façade of the palace. The design for this commission (which has been preserved) is the work of Manuel Gonçalves, one of the gentlemen of the household, who supposedly had an aptitude for painting, and good taste. However, we now know that this commission was executed by Michelangelo Corbi,Footnote 43 a relatively unknown Roman painter who remained on Melo's payroll until the latter's return to Lisbon in 1728. These arms are the earliest documented work attributed to Corbi and commissioned by Melo.

The arms were produced in the spring of 1708, and although they did not survive, we know what they looked like thanks to the engravings commissioned for De Bellebat's book (Figs 2, 3). These arms hung from the main gate of the Buratti palace, which was theoretically an infringement of the norms (diplomats who were not yet formally acknowledged could not use any insignia on their residences). This raises questions about the degree of incognito and the real reasons that led Melo to reject the first ceremonial which was attributed to him. There are many examples of diplomatic representatives exploiting the status of ‘incognito’, as it enabled them to elude obligations that should be complied with once they were instated, and could also be used as a tool for negotiating with the pope. It is tempting to interpret the presence of the Portuguese coat of arms in the Buratti palace as part of a political game between Melo e Castro and Clement XI; by pressuring the pope about the matter of his treatment, he could possibly obtain more quickly the privileges that his king demanded, or simply gain time to negotiate (Bodart, Reference Bodart, Colomer and Brown2003: 99–100). Thus, the arms hung on the façade of the palace were an unmistakable sign of the special envoy's desire to start negotiations, as well as a public reminder in the Roman court of the irregularity of his situation in not having had a ceremonial that was suitable for his position. In other words, we can conclude that displaying the arms was a very calculated measure to exert pressure to negotiate.

Fig. 2. Coat of arms of King John V, designed by Manuel Gonçalves and executed by Michelangelo Corbi.

Fig. 3. Coat of arms of Pope Clement XI, designed by Manuel Gonçalves and executed by Michelangelo Corbi.

We know about the unconventional placing of the arms that adorned the palace thanks to a payment made in June 1709 to Domenico Mottini, for the work of hanging them on the outside of the Buratti palace, and again when the embassy moved to the Cavallerini palace (later known as the Lazzaroni palace).Footnote 44

Regarding the design of the arms, two payments made in September 1709 appear to refer to two copper plates with carved and gilded frames by Corbi (which were intended for the court in Lisbon), and another two by ‘Emmanuel Gonçalves’ (for Father Jeronimo, also in Lisbon). It is possible that these reproductions were dispatched in an effort to document each step of the decoration of Melo's first diplomatic headquarters.

Corbi is one of the painters whose names appear regularly in the embassy's accounts; orders for his works are recurrent throughout Melo's sojourn in Rome, making him, along with Antonio David and Pietro Bianchi, one of Melo's preferred artists.Footnote 45 Corbi excelled in painting portraits and in producing copies, which he did in great numbers, both to adorn Melo's different residences and to send to the court in Lisbon. During Melo's first year in Rome many commissions of portraits and mythological and religious paintings were documented, as well as figurative architectural elements for the Buratti palace.Footnote 46

Particularly noteworthy are a series of portraits of the Portuguese monarchs which adorned the audience hall, and fulfilled the official requirements of representation. These portraits depicted not only the king and queen of Portugal but also the princes and brothers of John V, creating a type of genealogical tree that decorated the public halls of the palace and served as presents for allies of the Portuguese nation. Models were sent from Lisbon for the painters to produce as close a resemblance as possible to the royal subjects. Unfortunately, their whereabouts nowadays are unknown.

Finally, the payments registered in Melo's books also included the earliest mention of the Roman painter Odoardo Vicinelli (1683–1755). Trained by Giovanni Maria Morandi of Florence, Vicinelli was part of the Portuguese envoy's network of artists. Although this has not been documented until now, I believe that Vicinelli had close ties to the Portuguese world. He was a fellow student of Vieira Lusitano at the academy of the Florentine painter Benedetto Luti, and in his correspondence Vieira refers to Vicinelli as a friend. I have recently attributed to them a shared commission — a canvas for the celebration of the canonization of St Francis Solano and St Giacomo della Marca in 1726. Nothing is known about who commissioned the work, but the result was a painting by Vicinelli the whereabouts of which is unknown, and at least two preparatory drawings by Vieira in Vienna and Lisbon.Footnote 47

The fact that Vicinelli's name shows up in the accounts of the Melo household is important, as it enables us to determine that his first contacts with the Portuguese were established much earlier than was originally presumed, and helps to explain the working relationship that was established already in those years. Vicinelli was assigned the production of two allegorical paintings, one of Christian charity and the other of Roman charity. The fate of these paintings is also unknown, but it is believed that they were meant to decorate Melo's palace.

5. CONCLUSION

A detailed study of the receipts and payments for 1708 and for the first months of 1709 proved to be an excellent source for reconstructing the early days of the Portuguese special envoy in Rome. The absence, so far, of other types of documentary sources makes it difficult to establish a clear image of Melo's role in the Pontifical court at this very early stage. Therefore, the account books are practically the only means of obtaining information about one of the most important protagonists of Joanine diplomacy in Roman society. Comparing such mundane sources as payments and receipts with other primary sources like De Bellebat's Relation, which had a basically propagandistic nature, helps to shed new light on the daily life of the Portuguese legation in Rome. De Bellebat's work was intended to amplify the echo of a diplomatic mission which had modest success. The ceremonial that was achieved is reflected in his pages. Thanks also to a study of the annotations made in the account books it is possible to recreate the timeline that led to Melo's public presentation, and obtain more concrete and detailed information to support abstract concepts, such as status and magnificence, and understand the inner mechanisms of the embassy's palace.

It is now possible not only to confirm the original location of the first diplomatic headquarters of the Portuguese legation, but also to understand the challenges in finding and adapting a residence for the purposes of self-representation. The activities carried out to improve and prepare the palace are depicted in the account books, and a careful reading of them has allowed for a reconstruction of the network of relationships with characters such as Signora Albani and family members of the Portuguese envoy, showing how Melo engaged with the Roman society, following standard patterns of proven effectiveness. Likewise, the annotations of expenses referring to furnishings for the palace, such as the baldachin and coat of arms for the façade, reveal a clear acceptance and assimilation of Roman etiquette, while also providing valuable information about when the adaptation of the ceremonial occurred. Finally, this study reveals the first contacts with the artists who would later comprise the Portuguese cultural entourage in Rome.

The arrival in Rome in 1712 of the famous Portuguese ambassador D. Rodrigo de Sa e Meneses resulted in a lessening of the power and influence of Melo, who had played a crucial role in preparing that extraordinary embassy of the marquis of Fontes, and Fontes's astonishing success both in terms of goals achieved, and in terms of the image of the Portuguese Crown. André de Melo is a figure who deserves much more historiographic attention, both for the political importance of his mission, which he carried out with three successive popes, and his key role in establishing a positive image of Portugal in the world theatre.

Melo eventually found a palace which was better suited to his demands. The Palazzo Cavallerini was located in the via dei Barbieri, much closer to the via Papalis, thus giving him greater visibility in the Pontifical court. He moved to his new headquarters in January 1709, according to the payment registered by his majordomo.Footnote 48 The palace was prepared for hosting the sumptuous celebrations that were held after Melo's public entrance in April of that year. After more than a decade of loyal service to John V, André de Melo e Castro became ambassador. In 1719 he moved again, this time to the bigger and more luxurious Cesarini palace, but that is part of another story.