In the 1950s, the U.S. public began to hear a lot about Asia. The continent had “exploded into the center of American life,” wrote novelist James Michener in 1951.Footnote 1 He was right. The following years brought popular novels, plays, musicals, and films about the continent. Tom Dooley's Deliver Us from Evil (1956) and William Lederer and Eugene Burdick's The Ugly American (1958) shot up the bestsellers’ lists. The novel Teahouse of the August Moon (1951), set in Okinawa, became a Pulitzer- and Tony-winning play (1953) and then a movie starring Marlon Brando (1956). It competed with Anna and the King of Siam, a novel (1944), turned Tony-winning musical (1951), turned Oscar-winning film (1956). All told tales of Westerners doing good in the far corners of the world. As such, they offered upbeat parables about the United States in the global Cold War.

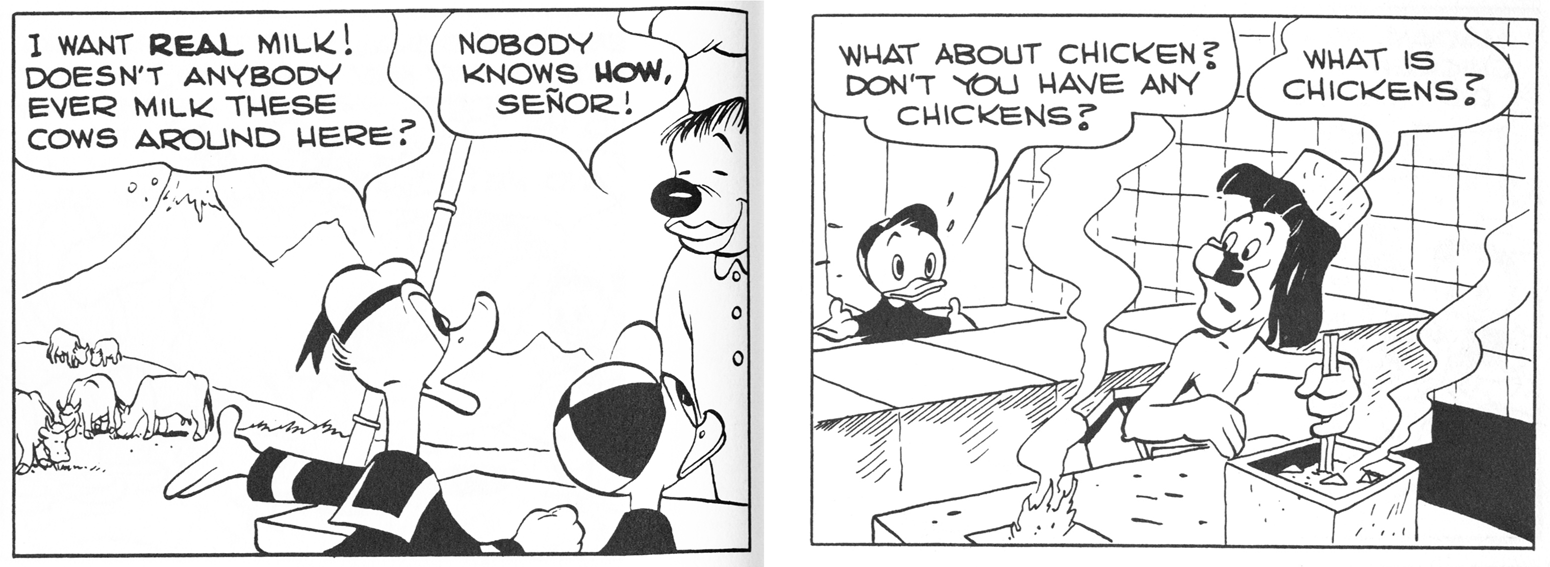

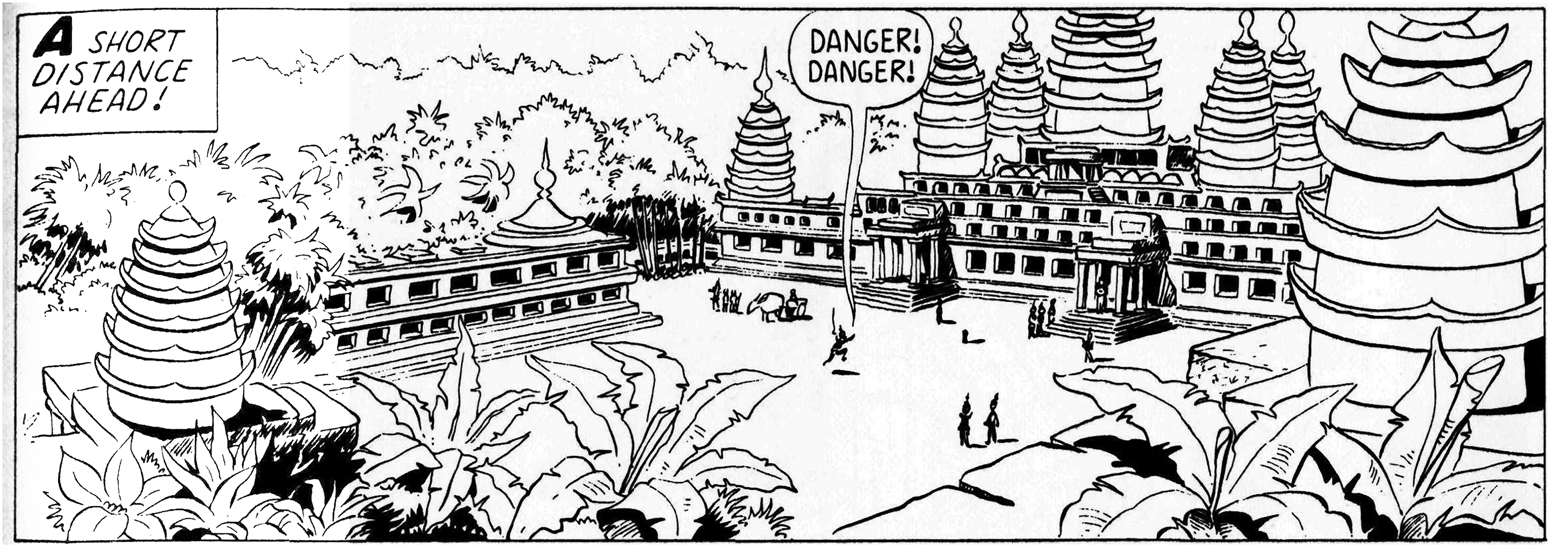

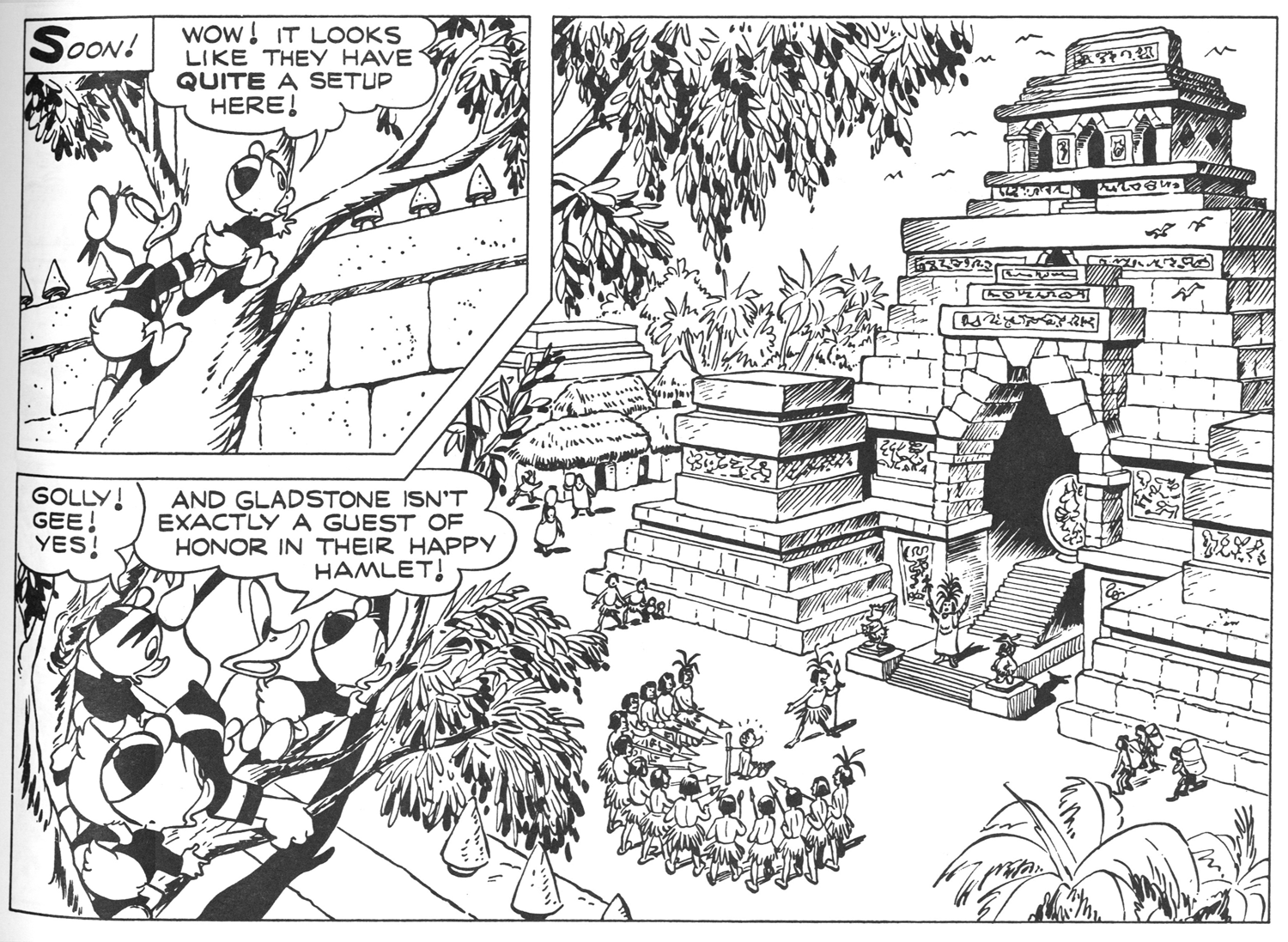

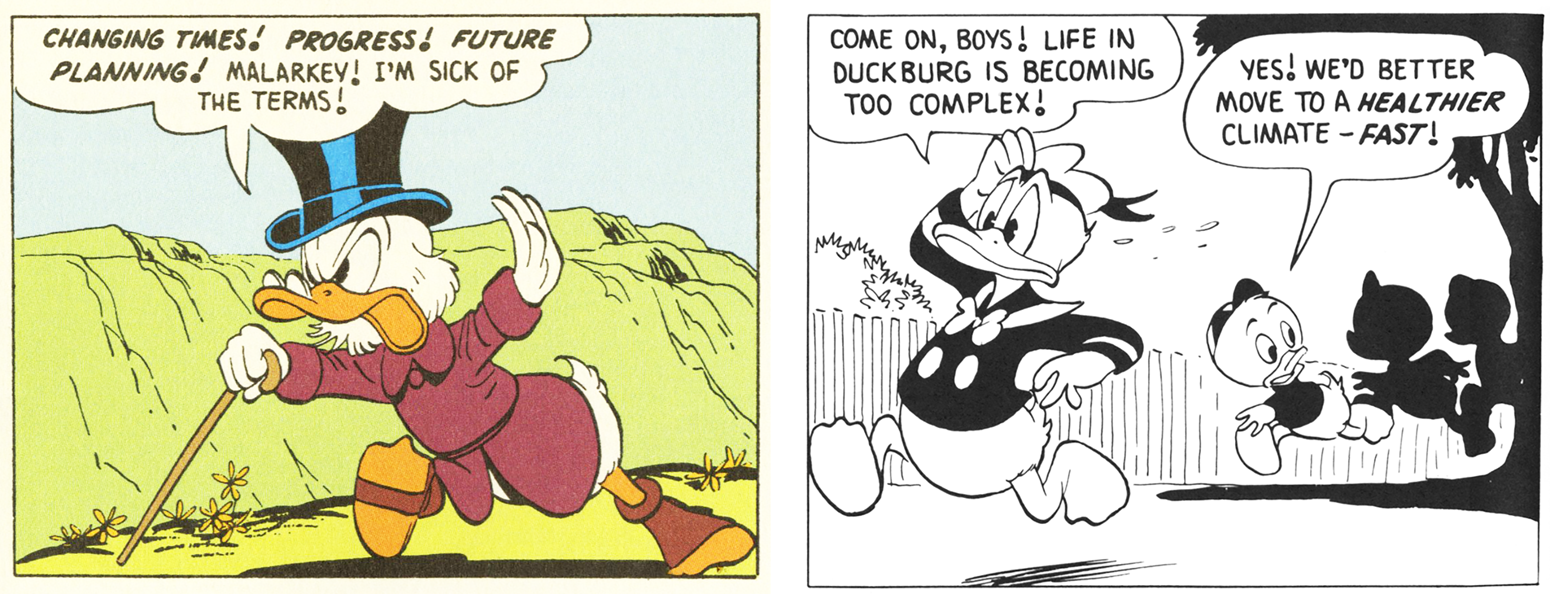

Yet not every story was uplifting. In a 1957 comic book, the Disney characters Uncle Scrooge, Donald Duck, and Donald's nephews Huey, Dewey, and Louie make their own journey to Asia. After taking a steamer to Indochina, they steer sampans up the “Gung Ho River” to a “stretch of wild country,” and find a “hidden city” not seen by outsiders for a thousand years: “Tangkor Wat” (Figure 1). There, they proceed to disrupt the city's traditional culture and destroy its palace. They enrich themselves, and they leave Tangkor Wat in ruins.Footnote 2 As the comic's author, Carl Barks, later explained, his tale was meant as a warning. “Ancient kingdoms and cultures of a beautiful people were about to be steamrolled by modernizers,” Barks wrote.Footnote 3 This comic book conveyed how much damage those modernizers could do.

Figure 1. The first glimpse of Tangkor Wat (Carl Barks, “City of Golden Roofs,” Uncle Scrooge #20, 1958).

It might be tempting to dismiss Barks's comic, which directly challenged core tenets of midcentury foreign policy making, as an anomaly. But Barks was the single most-read comics author of the period—and one of the country's most-read authors in any genre. Nor was foreign relations a side issue for him. He engaged the topic constantly; the Tangkor Wat story was just one item within a large corpus of extremely popular antimodernization tales that Barks published. A generation of young readers—the baby boomers—thus grew up regularly reading comics that rejected the intellectual foundation of their own country's official worldview.

What is more, there is reason to think that Barks left a mark on his readers. It is, of course, always hard to know what people made of the texts they read, and it is even harder to know what young people made of them. Yet there are peculiar features of the Barks corpus that help answer these questions. By following Barks's distinctive tropes into cultural texts produced by adult boomers such as Steven Spielberg and George Lucas, we can distinguish the imprint that Barks's stories of Uncle Scrooge and Donald Duck made. For not only did Spielberg and Lucas draw on Barks heavily in their films, particularly the Indiana Jones series, they also challenged the ideology of modernization in much the same terms he had. Moreover, their Barks-influenced films proved wildly popular. What this suggests is that Barks mattered. Through his comic books, he had offered his young readers scripts for a different understanding of U.S. foreign relations. When those young readers grew up, those scripts prove useful as, in the wake of the Vietnam War, they confronted their country's official worldview head-on.

At the core of that worldview—the ideology of modernization—was an understanding of how science, technology, industry, and their associated sociological transformations had carried countries like the United States into the vanguard of modernity. But it had an important political corollary. As a leading “modern” country, the United States could help “traditional” countries through their own process of modernization. That process, champions of modernization promised, would be beneficial, strategically desirable (so long as modernization did not take a communist form), and, with time, inevitable.Footnote 4

The ideology of modernization, dominant in official circles from at least World War II through the 1970s, played out on multiple levels. On the theoretical plane, social scientists converged on modernization theory, which Nils Gilman has described as the “highest flowering of American intellectual life” because it incorporated and integrated “many of the postwar period's dominant ideas about society, politics, and economics.”Footnote 5 At the level of practice, policy makers had modernization in mind when they staged their various interventions in the Third World (or, as it is often called outside of a Cold War context, the Global South). Christina Klein, meanwhile, has shown how the ideology of modernization “extended beyond the realms of the political elite and suffused contemporary popular culture,” informing movies, popular fiction, and theater.Footnote 6

A sense of this multifaceted modernization campaign can be got from examining the place of Thailand (called Siam until 1939) in U.S. arts and letters. Presbyterian missionary Kenneth Landon offered one of the most influential accounts of the country, an academic study titled Siam in Transition (1939), which argued that Siam was “adjusting to a technological world.”Footnote 7 Landon went on to work for the State Department and National Secretary Council, where he helped oversee hundreds of millions of dollars of U.S. foreign aid to Thailand to help it make that adjustment. In that period, Landon was the United States's leading Thailand expert and “the single person most responsible for the postwar alliance between the United States and Thailand.”Footnote 8

While Kenneth Landon scaled the commanding heights in Washington, his wife and fellow missionary, Margaret Landon, acquired a different sort of influence. She wrote an enormously successful novel, Anna and the King of Siam (1944). The novel describes the arrival in the nineteenth century of the British Anna Leonowens at the Siamese court, where she becomes governess to King Mongkut's children. Anna is a reformer, “someone who could fight with knowledge in the corner of the world where she found herself.” The king, who “has one foot in the modern world of civilization and science,” accepts her influence.Footnote 9

The novel and its gospel of modernization proved not only popular but enduring. Two years after publication, it was made into a film starring Rex Harrison. Then, in 1951, it became a Tony-winning musical, The King and I, starring Yul Brynner as the king. Brynner also starred in the 1956 Oscar-winning film of the musical. In it, the king seeks to make Siam a “modern, very scientific country.” He sings about the intellectual upheavals involved in learning, for instance, that the Earth is a ball suspended in space rather than a land lying on the back of a turtle. Yet the king is undaunted, and the musical concludes with his embrace of modernizing reforms.

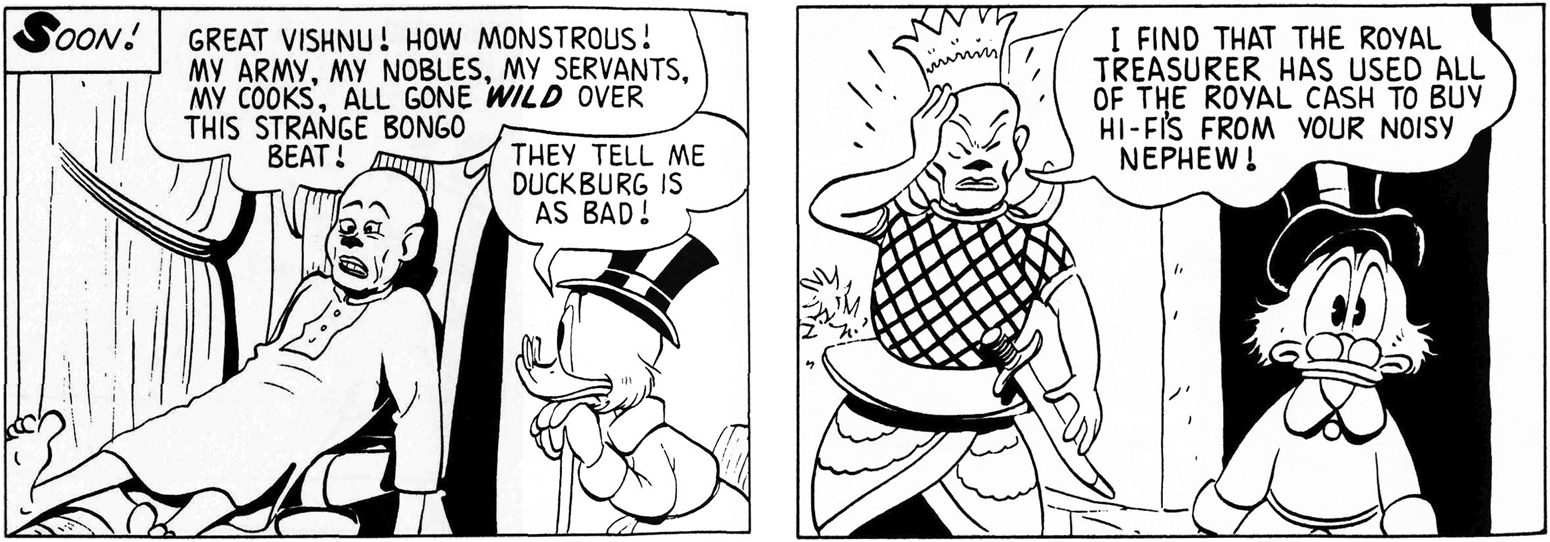

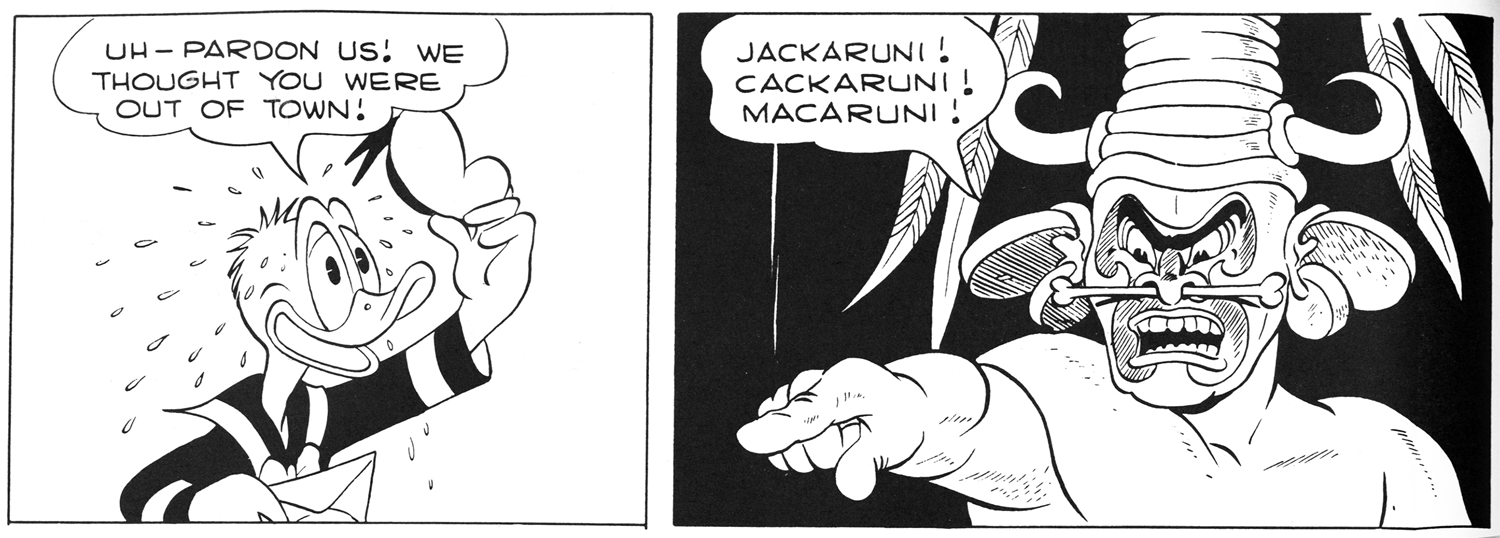

Christina Klein has identified The King and I, in its various incarnations, as a widely influential text.Footnote 10 One mark of its influence is that Barks's story about Tangkor Wat took the film as its inspiration. When the ducks arrive, they encounter a traditional monarchy whose king looks like Yul Brynner. But there the resemblance ends. The ducks do not come to Tangkor Wat as teachers, as Anna did. In Barks's version, they come as salesmen, selling miniature tape recorders, and they are met with alarm (“Danger! Danger!” are the first words uttered by an inhabitant of Tangkor Wat). The king shows no interest in science. Instead, he bemoans how the tape recorders have driven his once-loyal subjects “wild” and led them to abandon their duties. Seeing this, Scrooge cunningly encourages the unruly music fans to take up residence in the palace, where they create an unbearable din. Then, in exchange for driving them out, he tricks the king into allowing him to strip gold off the palace roof (Figure 2).Footnote 11

Figure 2. Modernization by duck in the Disney rendition of The King and I, with Scrooge McDuck facing off against a Yul Brynner lookalike (Barks, “Golden Roofs”).

The story ends well for the ducks but horribly for Tangkor Wat. The courtly culture—which Barks depicted with great sympathy—has been deranged, the royal treasury has been drained, and the palace roof has been melted down. Years later, Barks explained his intent in a short essay titled “Modernizing Tangkor Wat.” His story, he explained, had captured the “ominous drumbeat of doom” that had been sounding in Asia.Footnote 12 It was a warning about the consequences of U.S. intervention for the traditional cultures there. This was not a tale of a king bravely leading his country into the future, in other words. This was a story about a catastrophe.

If a monograph, a novel, two films, and a musical all told a story one way, how significant is it that a single story in a comic book told it another? In other words, how meaningful is it, really, that Barks's comic diverged from the party line concerning modernization? It may not seem meaningful, given comics’ place at the bottom of the cultural hierarchy. Yet if comics were lowbrow, they were not marginal. Children nourished themselves on a steady diet of them, available at the newsstand for ten cents. Adults read comics, too—a 1945 survey counted 41 percent of men and 28 percent of women between the ages of 18 and 30 as comic book readers.Footnote 13 For a brief moment, roughly from the end of the Second World War until their displacement by television in the late 1950s, comic books became one of the most important vehicles for the transmission of culture.

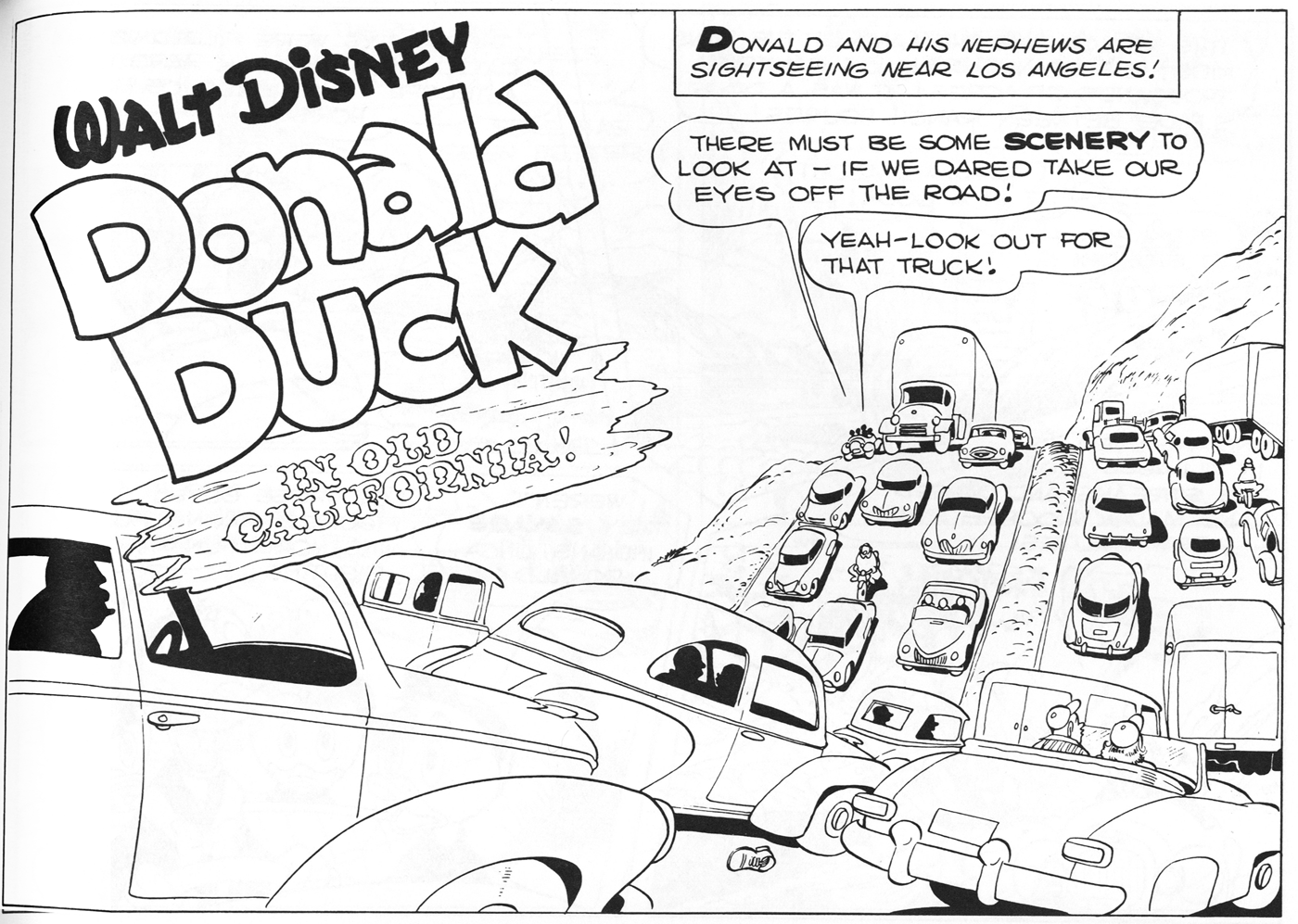

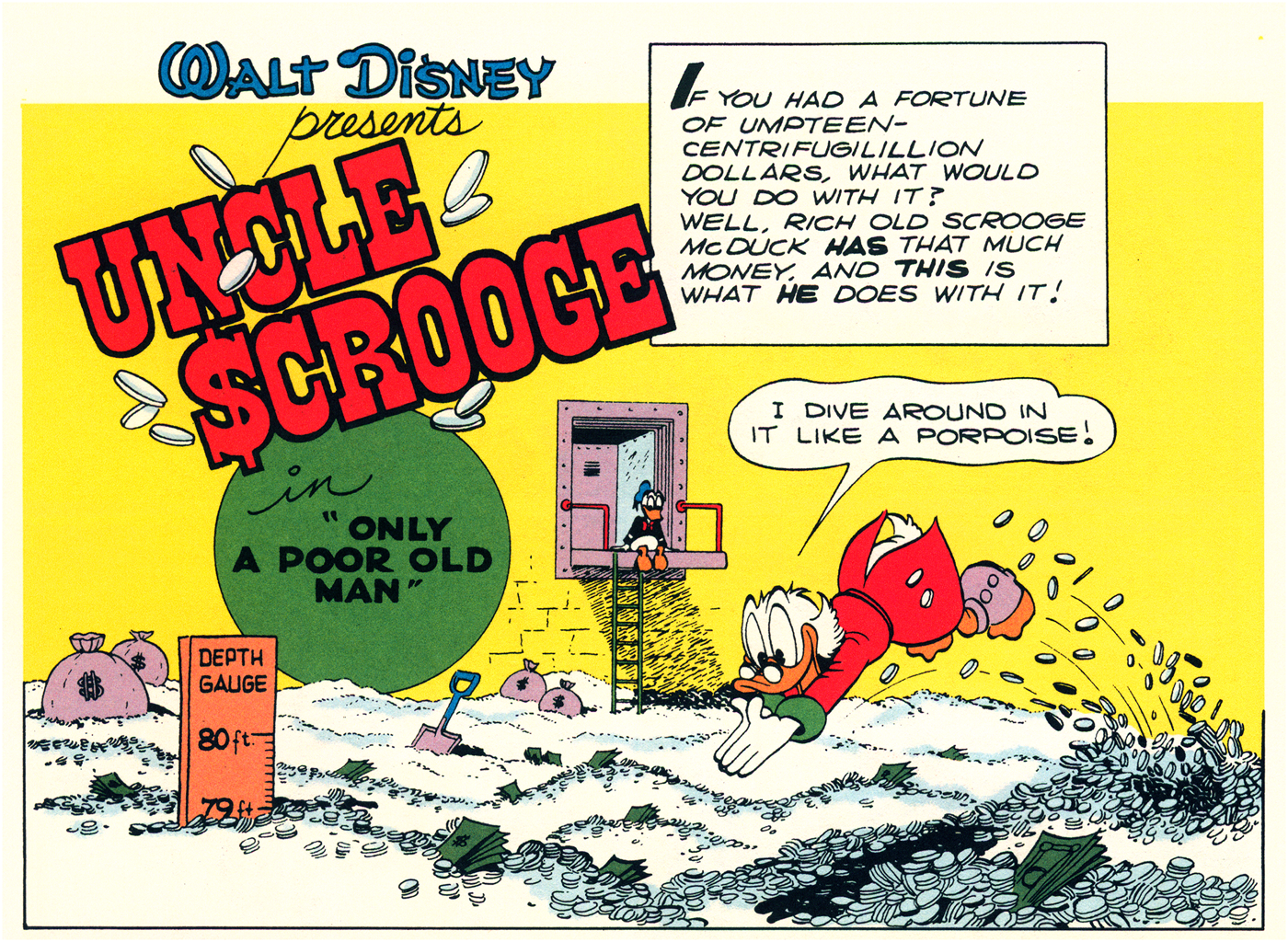

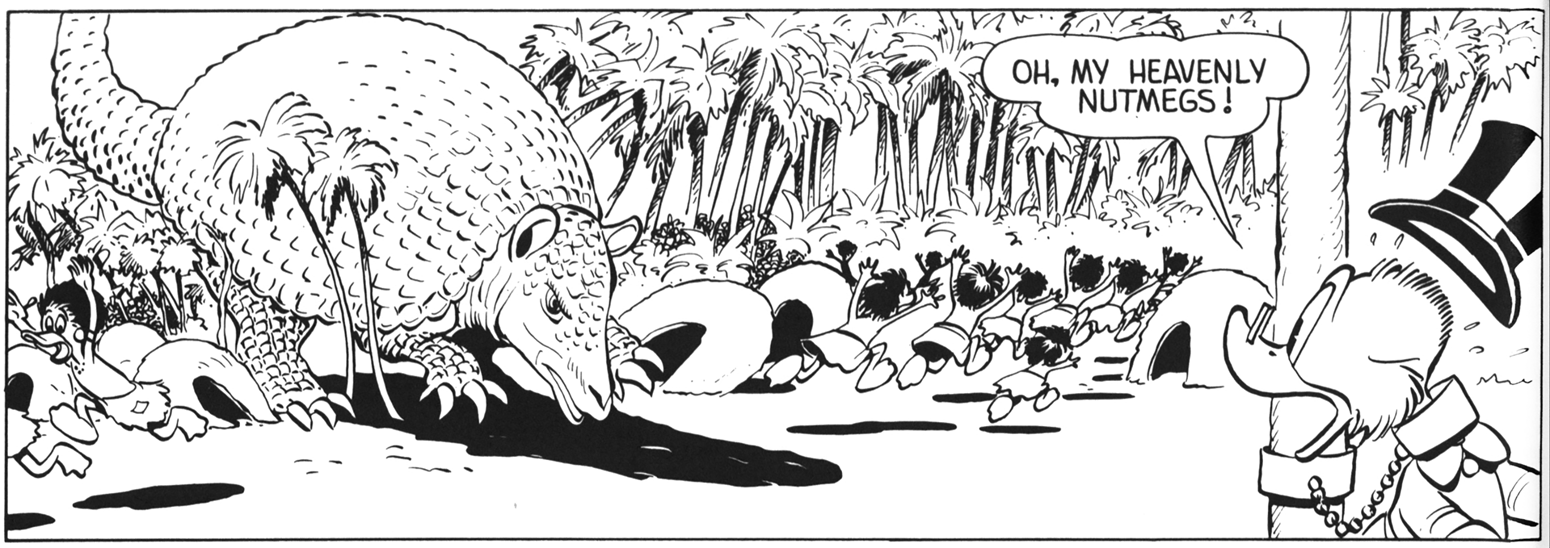

At the center of the comics boom stood a single intensely prolific creator, Carl Barks, who wrote, penciled, inked, and lettered the Donald Duck comic books published by Dell. Since comics featuring Disney characters were presented as the personal work of Walt Disney, Barks toiled in obscurity for nearly his whole career. Sharp-eyed fans, recognizing his superior craft and distinctive style, knew him only as “the Good Duck Artist.”Footnote 14 Yet from his home in the San Jacinto area near Los Angeles, where he handled every aspect of production short of coloring and printing, Barks created an astonishing corpus. He turned Donald Duck, an irascible film character known mainly for his sputtering incoherence, into a calmer and more articulate everyduck. Month after month, starting in 1943, he sent Donald on adventures in the company of his nephews Huey, Dewey, and Louie, adventures that often deposited the ducks in far-flung locales. Over the course of the more than 500 full-length stories he wrote, Barks built out Donald's world, adding characters, most notably the fantastically rich Uncle Scrooge McDuck, whose incessant search for wealth occasioned still more trips to the Global South (Figure 3). Scrooge soon surpassed Donald as a driver of newsstand sales.

Figure 3. Uncle Scrooge, swimming in his money bin, in Carl Barks, “Only a Poor Old Man” Four Color #386, 1952.

Those sales, it must be said, were staggering. Walt Disney's Comics and Stories, the principal though not sole vehicle for the ducks’ adventures, sold more than three million copies per issue at its peak in 1953.Footnote 15 That was more than Superman, more than any other comic.Footnote 16 It was significantly more, in fact, than the circulations of the New Yorker (0.4 million), Esquire (0.7 million), Newsweek (1 million), Time (1.9 million), or National Geographic (2.2 million). Only a handful of periodicals outsold it, among them the Saturday Evening Post (4.6 million) and Reader's Digest (10.2 million).Footnote 17 What is more, Walt Disney's Comics and Stories was joined by another duck title, Uncle Scrooge, which sold in comparable numbers, plus a torrent of one-shot titles in Dell's Four Color anthology series and various promotional issues (Barks produced comics given away in cereal boxes, at shoe stores, and at tire dealerships).Footnote 18

Comics also had important properties that other periodicals lacked. Not only did the duck comics sell well, they—like other comics—had extraordinary pass-along rates, with probably two to four readers per issue.Footnote 19 Those readers also revisited the comics frequently and in some cases obsessively, which cannot be as easily claimed for Newsweek or the Saturday Evening Post. Another distinctive feature is that the lead story in Walt Disney's Comics and Stories was almost always by the same author. It is thus not at all an exaggeration to crown that anonymous author, whom we now know to be Carl Barks, the most-read magazine writer of the 1950s.Footnote 20

Carl Barks was an unusual breed of literary lion. He grew up on what he called a “little wheat ranch” in southern Oregon, dropped out of school after the eighth grade, and had scant engagement with the high- or even middlebrow culture of his time. Among his few influences he cited Prince Valiant, Tarzan, and the pulp novels of Zane Grey, though he confessed to skipping the slow bits.Footnote 21 He supported himself as a logger and a member of a riveting gang until he found work drawing cartoons for the risqué Calgary Eye-Opener. He then moved to the Disney studio in the 1930s, where he worked as an animator (including, briefly, on Bambi), but he quit animation for comic books in the 1940s, where he found his calling. His career in comics maps neatly onto the chronology of high U.S. global supremacy: the first story he wrote and drew appeared in 1943, the last in 1967.

Despite his work's tremendous popularity, Barks lived in solitude. He alone handled the bulk of the production on his stories, venturing into the “big city” (Los Angeles) for “no more than a few minutes once or twice a month” to drop off his work, as he put it.Footnote 22 His publisher kept his fan mail from him (they “probably feared I would ask for a raise”), so that in his first seventeen years on the job he received only three letters.Footnote 23 His social world was further confined by his partial deafness and, early in his career, by his entrapment in an abusive marriage with an alcoholic wife.Footnote 24 The result was profound isolation. Barks had a counterpart in the funny animal–drawing business, Floyd Gottfredson, who drew the Mickey Mouse stories that appeared in the same comic books as Barks's Donald Duck stories. Yet though Barks admired Gottfredson and though both lived in California, it was not until the 1980s—nearly two decades after retiring—that Barks even met Gottfredson.Footnote 25

Barks was, in his own telling, “strictly a hack,” paid by the page, and paid poorly enough to feel significant economic strain for his whole career.Footnote 26 As was frequent in the industry, intellectual property rights went to Disney, not Barks—including for the endlessly lucrative character Uncle Scrooge. Thus, Barks was not paid royalties, he was not paid when his comics were reprinted or translated, and he was not paid in the 1980s when his characters and stories became the basis of a popular animated television show, DuckTales. Barks did not even receive copies of his own comics—he had to buy them from the newsstand.Footnote 27 He had been, as he put later it to a fan, “a sharecropper on old Marse Disney's animal farm.”Footnote 28

After Barks's retirement, an interviewer noted the central and—some might say—cruel irony of his career: Barks had been a piece-rate worker who had never saved enough for a vacation or even left the country, yet he had spent his working life spinning out hundreds of tales of travel, leisure, and prodigious wealth accumulation. “Oh heavens, yes,” Barks replied. “That's too true to be funny.”Footnote 29 And yet, from his lonely and not particularly luxurious perch in Southern California, Barks patched into the minds of millions of children. It mattered that he did this through the new genre of the comic book. Unlike comic strips, which appeared in all-ages newspapers, comic books were sold directly to children, at child-attainable prices.

The rapid emergence of comic books had caught the country by surprise. The first comic books appeared in the 1930s, and by 1945 they outsold regular books two to one.Footnote 30 It did not take long for fears of this new medium to arise, especially given the growing readership for lurid crime and horror comics. “The time has come to legislate these books off the newsstands and out of candy stores,” the noted child psychologist Fredric Wertham argued.Footnote 31 There were comic book burnings, boycotts, and censorship campaigns.Footnote 32 Eventually, the anti-comics backlash grew large enough to force the major publishers to self-censor through a morals code in 1954—the comic-book analog to film's Hays Code. Much of the comics market quickly withered.

Much, that is, except for the funny animal comic books. These were, Wertham allowed, the “mainstay of the ‘good’ comic books,” the least troubling of the newsstand offerings.Footnote 33 “Funny, gay animals,” wrote the author of one of the first book-length studies of comics, “who could possibly object to that?”Footnote 34 Not many, it seemed. The all-important Cincinnati Committee on the Evaluation of Comic Books registered objections to Superboy, Wonder Woman, John Wayne, G. I. Joe, and Tarzan, but not the Barks comics.Footnote 35 Barks's publisher, Dell, did not even submit its books to the industry's censorship code. Instead, it boasted in its “pledge to parents” that its own more stringent internal code “eliminates entirely, rather than regulates, objectionable material.”Footnote 36 Taking this high road appears to have worked. When other comic books failed (Captain America ceased publication in 1949), Dell's kept going. By 1957, after the dust settled on the censorship controversy, its titles accounted for a full one-third of all U.S. sales.Footnote 37

This assiduously cultivated aura of innocence helped abroad, too. It allowed Barks's comics to cross borders, including into countries, such as postwar West Germany and Japan, that were subjecting themselves to intense cultural scrutiny and were thus extremely cautious about what children read.Footnote 38 Through international sales of Barks's work, his creation Uncle Scrooge became a recognized figure worldwide. Interestingly, as Jean-Paul Gabilliet has observed, Scrooge is “the only character of an American comic to have acquired a global celebrity without relying on cinema or television.”Footnote 39

One Japanese comic artist, Osamu Tezuka, remembered how U.S. comics were “imported by the bushelful” into postwar Japan and “had a tremendous impact” there.Footnote 40 The Disney comics in particular drew Tezuka's eye. He adapted Barks's style—cartoonishly rendered main characters with enormous eyes and small bodies overlaid onto more realistically drawn backgrounds—to his own work, including the popular comic Astro Boy.Footnote 41 Tezuka's art in turn sparked the explosion of manga, the comic book form that dominated Japanese culture after the Second World War and gave rise to anime.

After television sapped his domestic audience, Barks remained prominent abroad, and remains so today. In the 1970s, the Los Angeles Times reported that Disney comics sold 250 million copies a year globally, a figure that Barks affirmed (some were new stories, many were reprints of Barks's work).Footnote 42 When the Argentinian writer Ariel Dorfman sought to address U.S. cultural imperialism, he chose as his subject the duck comics. His How to Read Donald Duck, written with Belgian sociologist Armand Mattelart, noted how ubiquitous they had become in Chile, where Dorfman and Mattelart then lived. Donald Duck, Dorfman wrote, was the “most imperialist of creatures.”Footnote 43

The character of Carl Barks's work can be gleaned from the first long duck story he wrote and drew, “The Mummy's Ring” (1943). In it, Donald and his nephews learn of an Egyptian ruler, the Bey of El Dagga, who is “sore at modern life” and wants everything changed “back to the way it was in ancient times.” As part of this campaign, the Bey reclaims—“under the threat of starting a war”—a pair of mummies that have lain at the Duckburg museum since 1878. But Donald's nephew Huey gets trapped in one of the Egypt-bound sarcophagi, and the ducks go there to rescue him. Discovering Huey, the Bey decides to kill him. He reconsiders only on seeing that Huey is wearing (as the result of a string of coincidences) the Ring of the Three Serpents, lost for three millennia. Elated to have the ring back, the Bey frees Huey and gives the ducks a treasure chest full of jewels.Footnote 44 Though not the most memorable of Barks's stories, “The Mummy's Ring” sets out the themes to which he would return over and over: world travel, the confrontation between the Global North and Global South, the transfer of wealth, the threat of violence, and the question of modernity. These are, not coincidentally, also themes raised by the ascent of the United States to a position of global supremacy in precisely the period when Barks wrote.

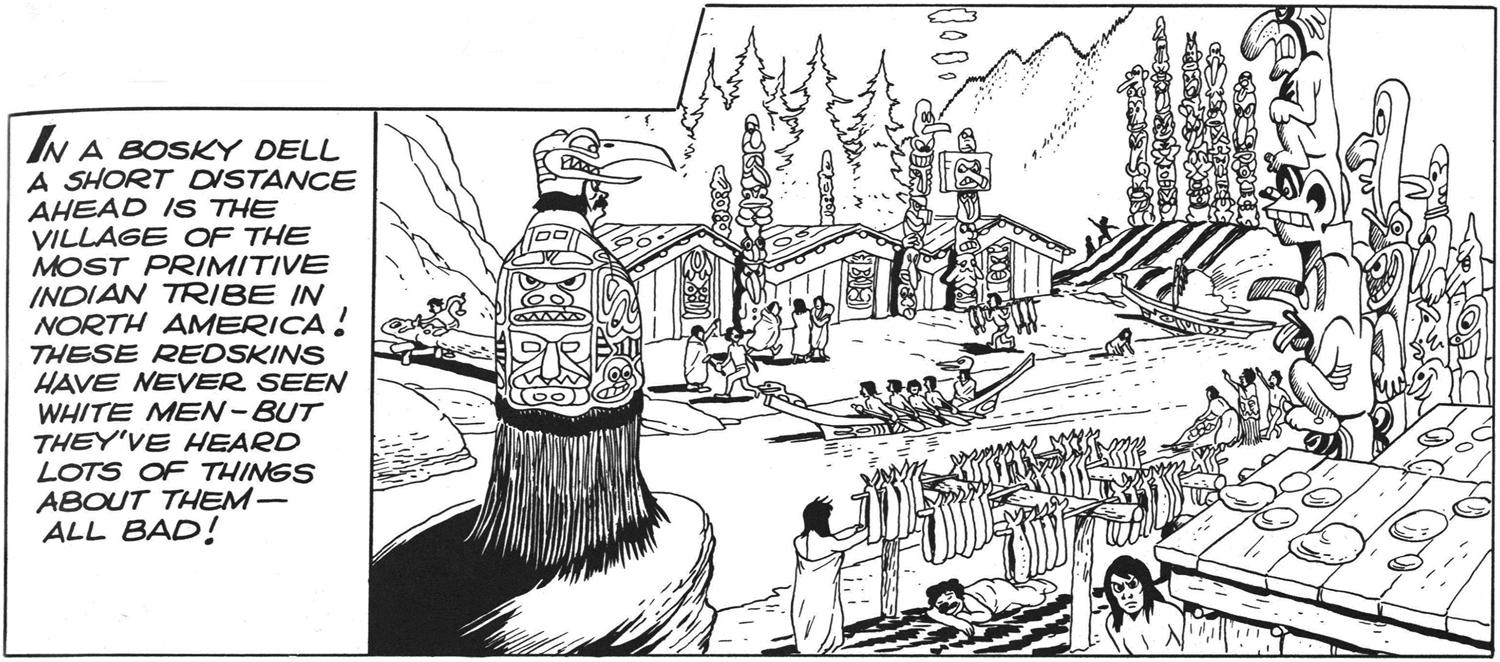

Travel is the most conspicuous element of the Barks stories. World War II had dramatically widened the horizons of the United States. By its end, the country had 5.3 million service members overseas and some 2,000 foreign base sites.Footnote 45 In the following years, consumer affluence, affordable aviation, and a heightened global ambition kept people traveling. By the 1950s, roughly 7 million U.S. citizens went abroad annually.Footnote 46 Barks was not in that number, but his comics nevertheless served as proxies for tourism. One of their most striking features was their carefully rendered ethnographic, architectural, botanical, and zoological detail, which immersed readers in foreign spaces (Figure 4). To achieve this, Barks referred frequently to his extensive collection of National Geographic magazines, occasionally copying scenes directly from photographs or illustrations (as he did in “The Mummy's Ring” and his Tangkor Wat story).Footnote 47 “I don't know exactly why I did so much research,” Barks said, “But I had the feeling that the ducks had to go to real places. Otherwise the stories would look silly.”Footnote 48

Figure 4. Rich ethnographic detail in Carl Barks, “Land of the Totem Poles,” Four Color #263, 1950.

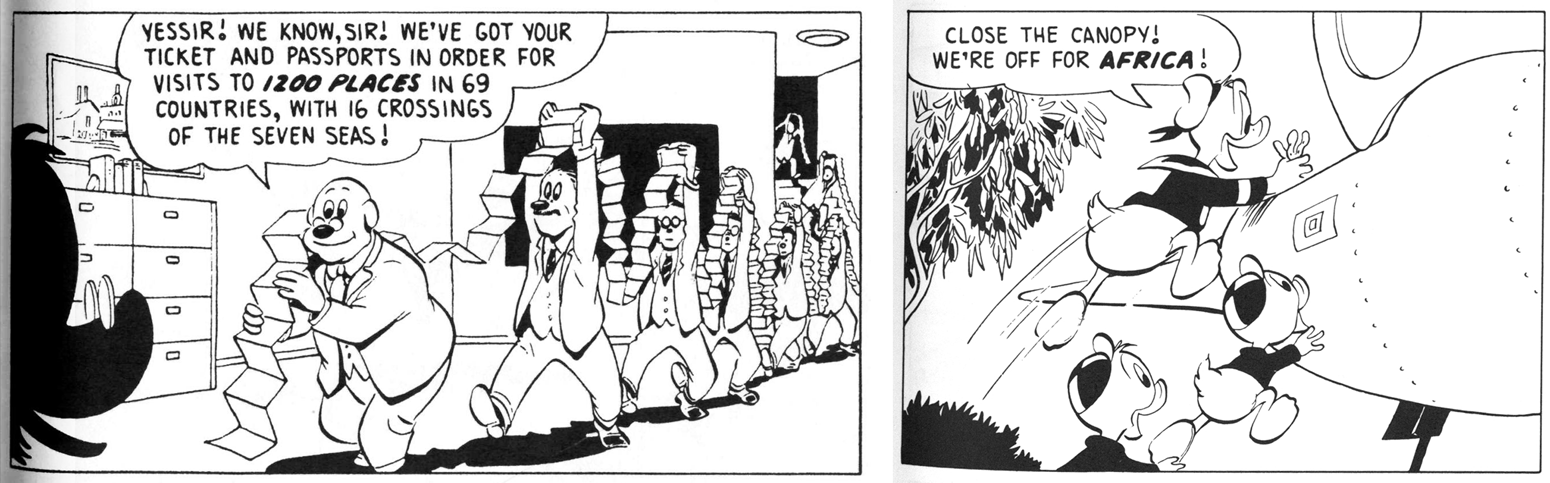

Barks put his National Geographic subscription to use. The ducks, especially in the Uncle Scrooge stories, travel aggressively: they charter planes, stow away on ships, and explore uncharted islands. It is noteworthy how much time in a typical Barks story is consumed by transit, as the ducks negotiate with travel agents or the owners of various vehicles (Figure 5). A later study of 428 Scrooge stories (most but not all by Barks) found that 83 percent of them featured nonlocal travel.Footnote 49

Figure 5. Scrooge prepares for a world tour in Carl Barks, “The Mines of King Solomon,” Uncle Scrooge #19, 1957, and Donald and the boys undertake one in an untitled story by Carl Barks in Walt Disney's Comics and Stories #212, 1958.

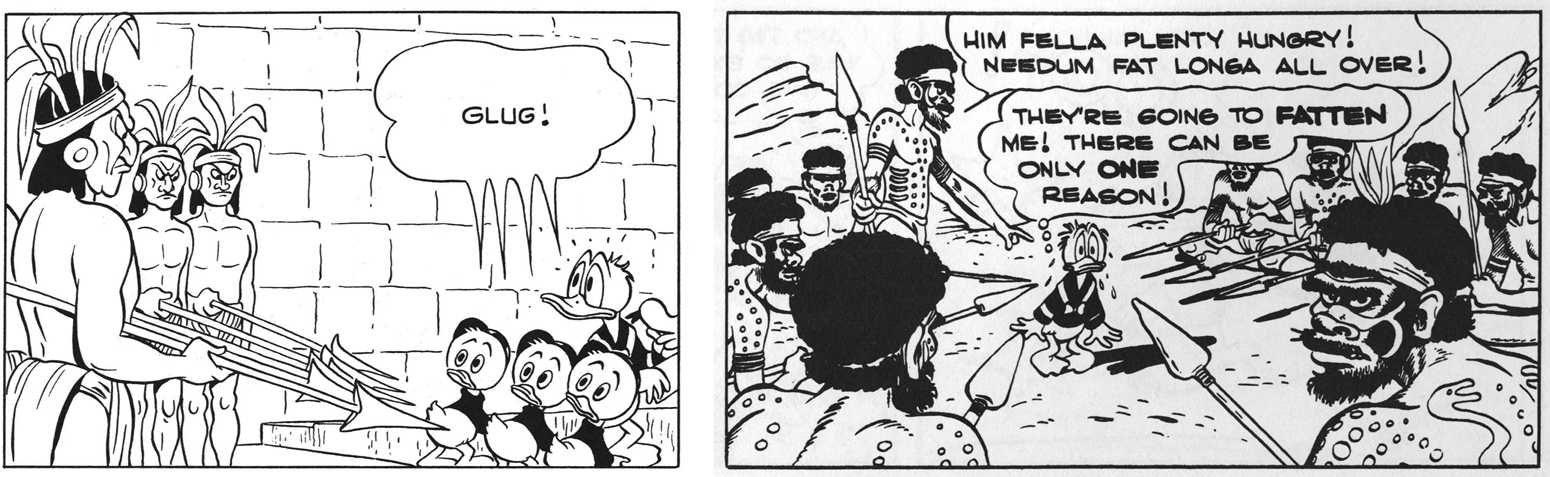

It may be tempting to see the ducks’ ceaseless quest for remote corners of the earth as a replay of nineteenth-century, flag-planting imperialism. Yet Barks avoided portraying the ducks as conquerors or plunderers. The violence, in his imagination, pointed in the opposite direction. It is the inhabitants of the Global South, such as the Bey of El Dagga, who threaten the ducks, not the other way around. Indeed, Barks depicted many of the stories’ Southern antagonists as standing more than twice as tall as the diminutive ducks.Footnote 50 The ducks hardly ever prevail in a simple physical contest (Figure 6).

Figure 6. The threat of violence, faced in British Guiana and Australia (Carl Barks, “The Gilded Man,” Four Color #422, 1952, and Carl Barks, “Adventure Down Under,” Four Color #159, 1947).

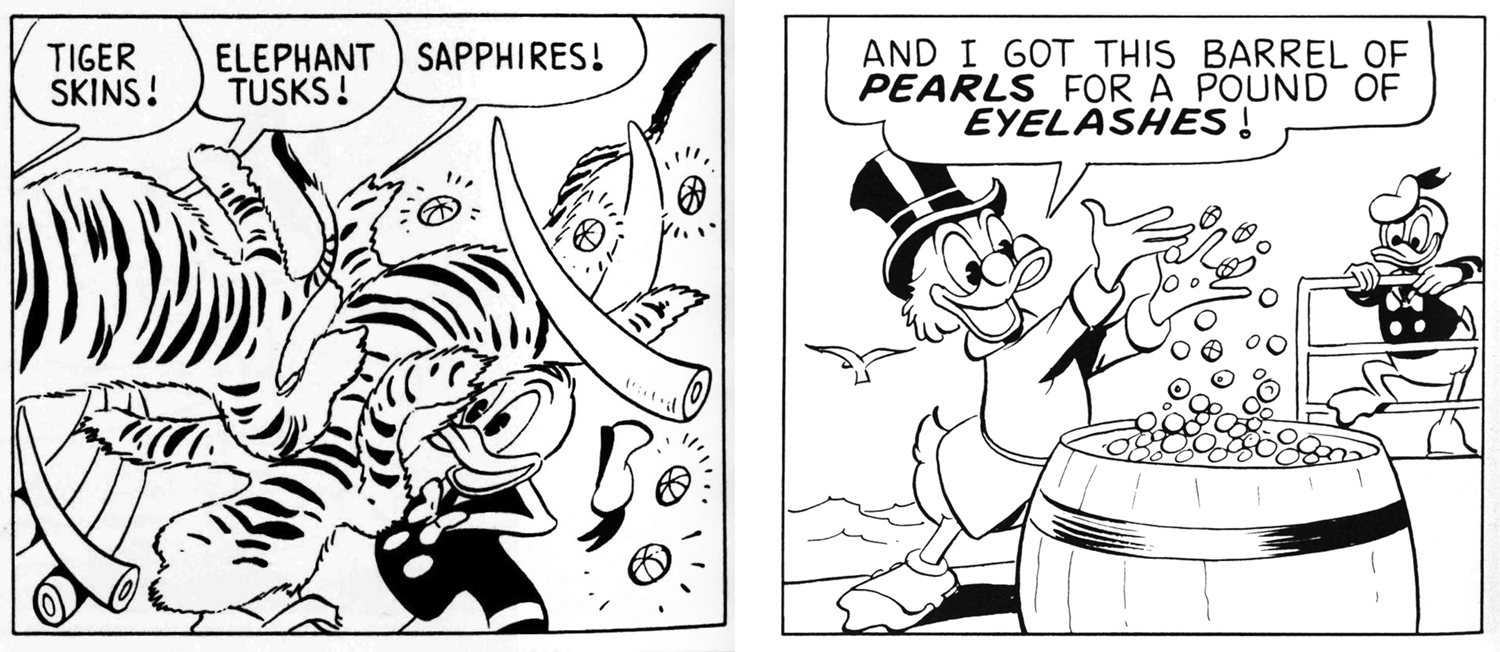

As Dorfman and Mattelart argue, imperialism is present in the duck comics, but masked. Rather than showing Southern economies forced into disadvantageous relationships with the United States, the comics depict the inhabitants of Asia, Africa, Latin America, and the Pacific voluntarily throwing their wealth into the ducks' arms (Figure 7). Oppression is obscured, exploitation naturalized.Footnote 51 Although Donald Duck was not known as a treasure hunter when Barks inherited the character, wealth transfer indeed became a dominant theme in the duck comics on Barks's watch. Interestingly, this was partly the doing of Barks's audience. Though he rarely gave editorial guidance, Barks's publisher noted that whenever Barks included Donald's rich uncle Scrooge McDuck in the action, sales jumped. At his publisher's urging, Barks developed Scrooge into a standalone character, which cemented the centrality of money in the duck adventures.Footnote 52

Figure 7. The ducks, showered with riches, in Barks “Golden Roofs” and Carl Barks, “Hall of the Mermaid Queen,” Uncle Scrooge #68, 1967.

When handling questions of wealth and treasure, Barks took care to uphold the propriety of the ducks’ activities. In his first appearances as a supporting character, Scrooge had been a cruel half-villain (in one early story he recounts how, to acquire a rubber plantation in Africa, he had “hired a mob of thugs” to chase a “tribe of ferocious savages” off their land).Footnote 53 But in promoting Scrooge to a starring role, Barks softened the character. Barks delved, as he put it, “into the old boy's past, into how he founded his fortune … all to prove that he deserved to be so rotten rich.”Footnote 54 Indeed, in the first issue of Uncle Scrooge, the nephews ask him how he made his money. Banking? No, Scrooge snorts. “I made it on the seas, and in the mines, and in the cattle wars of the old frontier! I made it by being tougher that the toughies, and smarter than the smarties! And I made it square!”Footnote 55

The hallmark of Scrooge's square dealing is his steadfastness in upholding contracts. Scrooge and his kin enter into agreements constantly, both with each other and with foreigners. Trickery is entirely permissible in these deals, as when Scrooge agrees to pay his weight in diamonds to a maharajah but then inhales helium until he weighs “sixty pounds less than nothing,” requiring the maharajah to pay him diamonds.Footnote 56 Reneging, however, is forbidden. A surprising number of Barks's plots hang on the obligation of characters to adhere unwaveringly to the terms of their agreements (Figure 8).

Figure 8. Though appearing on a television show will cost Scrooge a billion dollars in taxes, he cannot condone canceling and going back on his word (Carl Barks, “The Colossalist Surprise Quiz Show,” Uncle Scrooge #16, 1957).

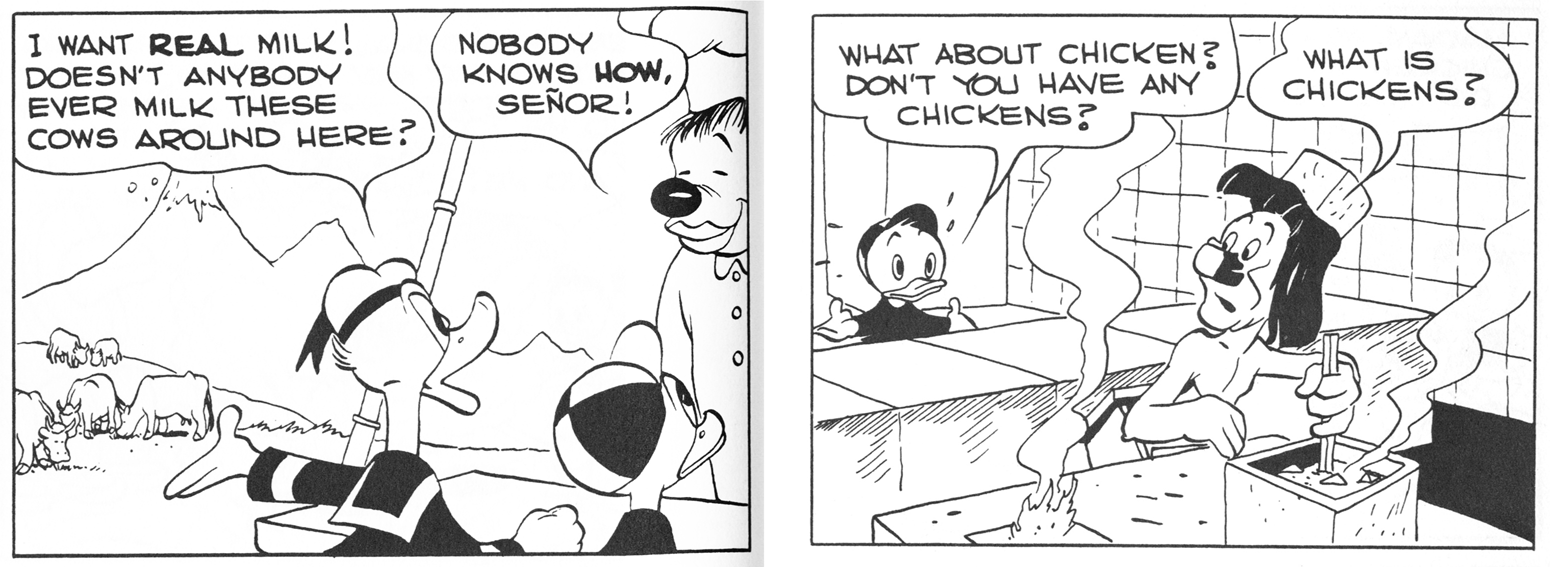

Barks justifies Scrooge's wealth by presenting him as an honest broker. And he justifies the poverty of the Global South by showing its inhabitants to have weak claims on their resources. They appear consistently in his stories as unintelligent. The Volcanovians—thinly disguised Mexicans—are so lazy and siesta-prone that one takes a nap while flying a plane (“What a nitwit!” Donald opines).Footnote 57 The Plain Awfultonians (Peruvians) eat exclusively eggs but cannot find the chickens who lay them—the ducks locate the chickens in minutes.Footnote 58 A dangerous mystery has been tormenting the West Indians around Skull-Eye Reef since the time of Sir Francis Drake, until the ducks solve it immediately.Footnote 59

More importantly, the ducks’ trading partners prove to be indifferent holders of wealth. They part with it easily and seem clueless about its value (Figure 9). A South American ruler owns a $50,000 stamp but cares only for the mail sack containing it, because he is “fascinated by its big silver buckles.”Footnote 60 A Samoan chief swaps one of the most valuable jewels on earth for some candy.Footnote 61 A Venusian trades Scrooge a moon made entirely of gold for a box of dirt.Footnote 62 Putting it together, the picture is clear: Fair-dealing, clever ducks encounter stupid and occasionally violent foreigners who do not value the treasures they possess. No wonder Scrooge has a money bin and they do not.

Figure 9. The basics of agriculture elude the people of Central America and the Andes in Carl Barks, “Volcano Valley,” Four Color #147, 1947, and Carl Barks, “Lost in the Andes,” Four Color #223, 1949.

Rich versus poor, modern versus traditional: these binaries are the building blocks of the ideology of modernization. They're the building blocks of Barks's worldview, too. But he assembled them in an altogether different way.

The central claim of modernization is that traditional societies can become modern, that they can “develop,” and 1950s comics did not shy away from that message. As Victoria Grieve has shown, the Lone Ranger comics regularly propounded the idea that the people of the Global South required the benevolent aid of the United States, with the Native American character Tonto serving as a model—a “willing partner in the modernization of his native lands,” Grieve writes.Footnote 63 The Lone Ranger comics, also published by Dell, were among the best-selling titles of the decade (though they did not match the ducks’ sales).Footnote 64

Indeed, modernization was ubiquitous in 1950s comics. When, in an August 1955 story, Batman travels to the Stone Age and meets a prehistoric masked superhero, Batman introduces him to modern technologies, including aviation and tear gas (“to drive away your enemies”). “It was men like him who started us all on the road to civilization!” Batman exclaims.Footnote 65 The next month, comics fans read of Superboy finding a city “cut off from the outside world.” After Superboy ends its isolation, the society's leader promises him to “adjust to your society and the marvels you have described.” “I've brought a new life to a world of the past,” Superboy proudly reflects.Footnote 66 The month after, readers got a similar story: Mickey Mouse discovering a Western ranch lost in time, with “no contact with the outside world.” Mickey shows the ranch's owner the virtues of automobiles and convinces him to buy a jeep.Footnote 67

Against the backdrop of such modernization-minded tales, Barks's oeuvre stands out. Consider again his first story, “The Mummy's Ring.” It begins with a tradition-obsessed ruler determined to revert his lands to their ancient state—exactly the opposite of the Siamese king's mission in Margaret Landon's book. What is more, Barks's Bey of El Dagga achieves his goal. The sarcophagi and ring return to Egypt, the ducks return to Duckburg, and everything ends up in its proper place. The drama is not about transformation; it is about restoration. Many of the duck stories end, as “The Mummy's Ring” does, with stasis. A foreign culture is restored or left intact. In numerous stories, the duck discover a previously unknown society, only to forget about it or to agree never to speak of it again.Footnote 68

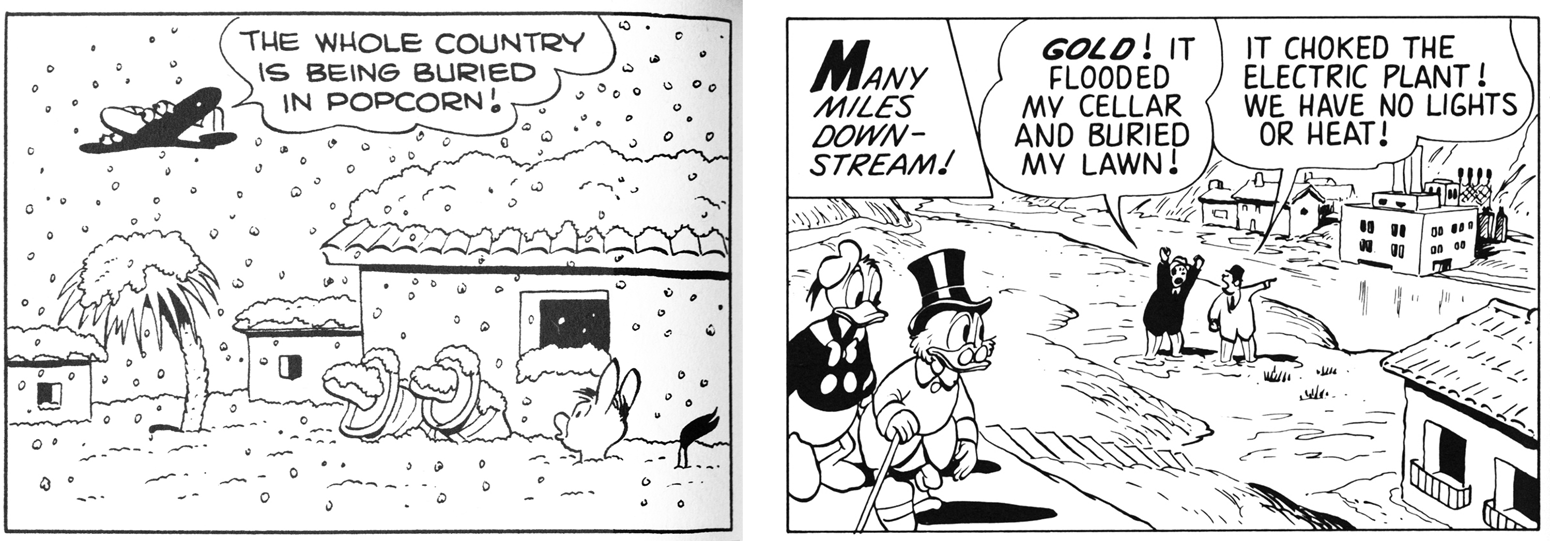

Yet stasis, in Barks's world, is a fortunate outcome. In other stories, such as the Tangkor Wat tale, the ducks wreak havoc (Figure 10). Frequently, the artifacts of mass culture or high technology are to blame. Jukeboxes, introduced by the ducks, drive the inhabitants of the underwater civilization of Atlantis (based, Barks suggests, on Egypt) “loco.”Footnote 69 Barks uses the same word, “loco,” to describe the effect that steam technology has on the First Nations of British Columbia.Footnote 70 In the Himalayan mountains, Scrooge finds a happy society in which money is unknown. But by the time he leaves, he has buried it in bottlecaps, wrecking its farms.Footnote 71

Figure 10. The ducks drown a Central American country in popcorn and an Andean city in gold before escaping in Carl Barks, “Volcano Valley,” Four Color #147, 1947, and Carl Barks, “The Prize of Pizarro,” Uncle Scrooge #26, 1959.

There is an unmissable irony here: Barks, master of the comic book, is lamenting the deleterious effects of mass culture. There is also some sadism. It is as if Barks were channeling the destructive impulses he could not express in other ways. He had to be “tooth chatteringly careful,” as he put it, about sex, death, and interpersonal violence in his stories.Footnote 72 He even once got in trouble with his editor for having Donald tell his nephews to “shut up.”Footnote 73 Yet Barks could show the ducks visiting disaster on Southern societies. This they did—regularly, spectacularly, and without looking back. “I think the conquest of the West was a disgusting sham,” Barks wrote to a fan. “The senseless fecundity of white immigrants to the New World is the calamity of the ages.”Footnote 74 The ducks, in discovering untouched civilizations and scrambling them, play out that calamity on the page, again and again.Footnote 75

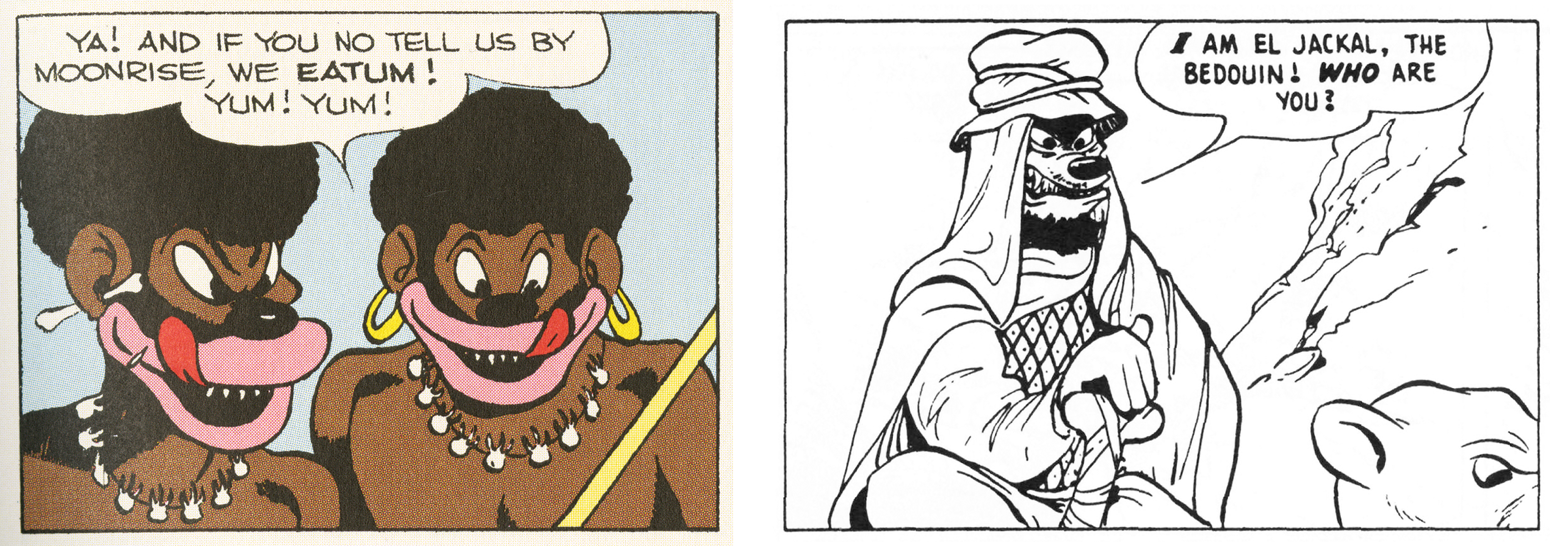

Barks could imagine his heroes leaving the Global South alone or wrecking it, but he had a harder time imagining that they might help it. He largely rejected that possibility—which other comics affirmed so readily—because he did not see the people of Asia, Latin America, Africa, and Oceania as fit for modernization. In this, Barks drew heavily on older literary tropes, ones that divided cultures not into “backward” and “advanced”—a scheme that implies possible movement—but into the more static and unbridgeable categories of “savage” and “civilized.” Barks's ducks travel incessantly in the Global South, but the people they encounter are of the most traditional sort—their trips to Africa take them to villages of huts, not to Lagos or Nairobi.Footnote 76 And the traditional societies they encounter teem with some of the most discomfiting colonialist stereotypes: childlike natives, noble savages, African cannibals, lazy Pacific islanders, and deceitful Arabs. In this, Barks bucked a trend in comics after World War II against overt racism in depicting foreigners (Figure 11).Footnote 77

Figure 11. Nineteenth-century colonialist racism of the starkest kind abounds in Barks's work, as in Carl Barks, “Darkest Africa,” Boys and Girls March of Comics, #20, 1948, and Carl Barks, “The Mines of King Solomon,” Uncle Scrooge #19, 1957.

Barks imagined a large gulf separating the people of the Global South from the denizens of Duckburg, and he built that into his visual style. He was a master of detail whose renditions of foreign landscapes could approach photorealism. Yet Barks always drew Donald and his family as cartoons—their faces flat white circles, with little shading, detail, or three-dimensionality (Figure 12). This is a technique called “masking,” which, as comics theorist Scott McCloud observes, allows readers to map themselves onto the schematically drawn protagonists. “When you look at a photo or realistic drawing of a face,” McCloud writes, “you see it as the face of another.” But when you look at a cartoon face, without too much specifying detail, “you see yourself.”Footnote 78

Figure 12. Barks's use of masking to distinguish the ducks from their background in Carl Barks, “Secret of Hondorica,” Donald Duck #46, 1956.

Barks did not just use masking to distinguish subject from object. He also used it to distinguish domestic from foreign. His most detailed backgrounds tended to be the faraway settings he had copied from National Geographic, whereas he drew Duckburg scenes more cartoonishly. Barks used his realistic style more on foreign people, too, especially those that posed threats (Figure 13). In so doing, he subtly signaled which characters were eligible for identification from readers and which were not. The inhabitants of the Global South appear, in Barks's stylistic vocabulary, less as characters than scenery. If the ideology of modernization rested on the universalist notion that even the King of Siam could and should learn science, Barks, in both form and content, depicted a world of irreconcilable difference.Footnote 79

Figure 13. Barks's use of masking to differentiate the ducks from foreigners in this two-panel sequence from Barks, “Gilded Man.”

Understanding Southern peoples as irredeemably primitive and cultural contact as disruptive led Barks to scoff at foreign aid. He did this in his adaptation of The King and I, but, remarkably, that was not the only developmentalist classic Barks took on. Five years later, he penned a version of William Lederer and Eugene Burdick's The Ugly American (1958). In that novel, the titular ugly American, ironically a hero, ventures to the fictional Southeast Asian country of Sarkhan, where he seeks to aid rice growers pump water into their terraced paddies. Working with a Sarkhanese helper, he invents a treadmill-powered pump using local materials that becomes popular, eases the burden of farmers, and generates a local pump-manufacturing business. The book became a bestseller, making an especially deep impression on John F. Kennedy, who started the Peace Corps in part under its influence.Footnote 80

The setting in Barks's version is the same: rice paddies in Southeast Asia, this time in the “less advanced” land of Farbakishan. Gyro Gearloose arrives from Duckburg as the proud representative of the “Brain Corps” and invents a treadmill-powered water pump. “Your troubles are solved, good people of Farbakishan!” he exclaims. Yet his invention quickly proves calamitous and Gyro flees. “I—I think I better get out of the country before I have another idea!” he stutters as he races away. A narrator's voice offers the grim conclusion: “Farbakishan stays un-uplifted, its people toiling like beasts.”Footnote 81

Barks's response to The Ugly American is even more remarkable because The Ugly American itself already represented a dissent from the ideology of modernization. In opposition to disruptive science- and technology-based impositions from abroad, the novel proposed a form of development in which poor societies would improve through community building, grassroots action, and slow cultural adaptation.Footnote 82 The authors of The Ugly American were not the only ones enamored of this vision. A large number of intellectuals, policy makers, and development practitioners favored this softer, less intrusive approach to development.Footnote 83

But not Barks. What distinguished him from modernizers like the Landons was not a preference for a more participatory style of development. It was his rejection of the possibility of development altogether. Barks dissented not just from modernization, in other words, but from developmentalism tout court. He shared with modernizers a vision of the world as divided into traditional and modern, but he lacked their optimism that the gulf could be bridged (Figure 14). Strikingly, Barks voiced doubts as to whether it should be bridged. Even for the ducks themselves, modernity does not appear in his stories as an unalloyed good.

Figure 14. Donald Duck, as a “Tutor Corpsman,” comes to teach “ignorant savages smarter ways to make a living” but ends up terrorizing them by unleashing giant animals on their village (Carl Barks, “A Spicy Tale,” Uncle Scrooge #39, 1962).

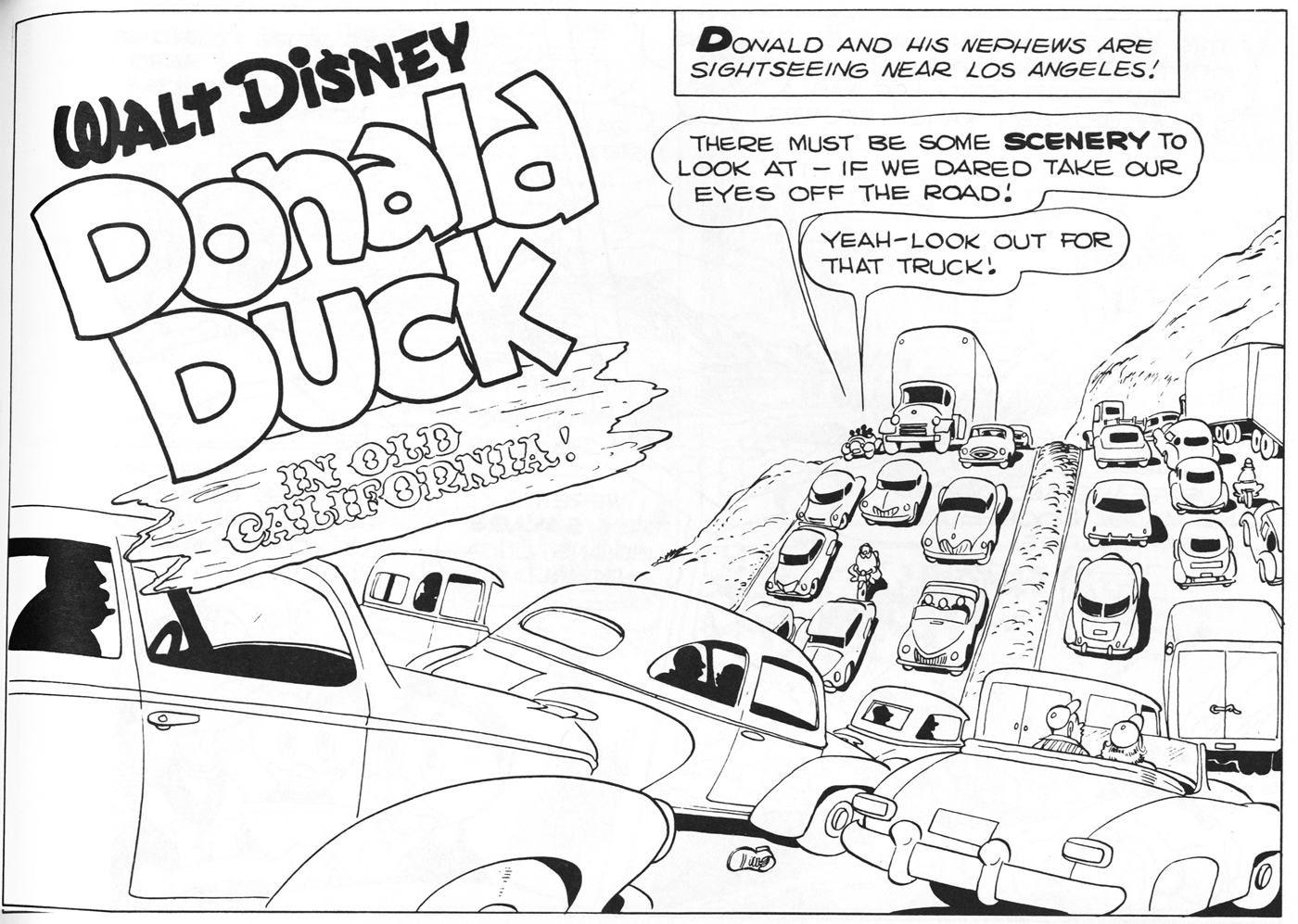

Barks's favorite of those stories was “In Old California” (1951), a tale of travel not in space but in time.Footnote 84 In it, the ducks drive around Southern California—Barks's own region—and are overwhelmed by the traffic (Figure 15). A frustrated Donald tells his nephews about California before the gold rush. It was “a land of peace and happiness,” Donald explains, where “there was plenty for everybody, and nobody wanted much.” Soon enough, the ducks have a car accident, fall into deep comas, and are mentally transported back more than a century, to California as it was “before the white men came” (Barks does not count the Spanish as white). Barks conjures up an innocent time, marked by a romantic culture and interracial harmony. Eventually, the discovery of gold destabilizes Old California and the ducks wake up. But, remembering their adventure, they seek out a dilapidated old ranch and serenade it, as passing motorists look on in confusion.Footnote 85

Figure 15. Donald and his nephews explore the region where Barks himself lived, an uncomfortably auto-stuffed Southern California of the 1950s, before being carried back a century in Carl Barks, “In Old California,” Four Color #328, 1951.

Comics historian Bradford Wright has argued that Dell comics never “questioned the state of American society.”Footnote 86 But a sense that modernization has overshot its mark—on ready display in his California story—pervades Barks's writing for Dell, often serving as a plot point. A number of stories begin with the ducks bemoaning life in Duckburg and yearning for something simpler. “I want to leave Duckburg with its smog and noise and shoving people,” Scrooge declares at the outset of one, “even though I am the guy that started all of these smelly industries!”Footnote 87 “I want to get away from my money!” is his lament at the start of another (Figure 16).Footnote 88

Figure 16. Scrooge, in peril of having his land flooded by a hydroelectric dam, attacks the premises of modernization in Carl Barks, “Migrating Millions,” Uncle Scrooge #15, 1956. Donald and the boys flee Duckburg for a simpler life abroad in an untitled story by Carl Barks in Walt Disney's Comics and Stories #201, 1957.

It is hard not to hear in these soliloquies the voice of Barks himself, who carefully limited his time in the city to mere minutes a month. When comics fans learned the Good Duck Artist's identity and interviewed him, they found a man profoundly uncomfortable with his own society. “I think the philosophy in my stories is conservative—conservative in the sense that I feel our civilization reached a peak about 1910. Since then we've been going downhill,” Barks explained.Footnote 89 He disliked television, he disliked most movies, and he complained that the United States tended “to make everybody exactly alike.”Footnote 90

Barks's skepticism of modernity and mass culture, not just his pessimism about the capacities of inhabitants of the Global South, led him to doubt whether the United States could play a useful role in world affairs. One reason he had left animation for comics during the Second World War, interviewers discovered, was that he had been “with the America First type of guys,” had “despised the darned war,” and had refused to participate in making war-related films for Disney.Footnote 91 “We didn't give a damn which side won as long as we could stay out of it,” he said.Footnote 92Stay out of it would not be a bad slogan for Barks's political vision. His was a world of fragile traditional societies and recklessly expanding modern ones, with no suggestion that the two might reconcile. In the duckverse, it is hard to imagine any productive collaboration between North and South.Footnote 93 The best one can hope for is protective segregation.

At the end of his career, Barks grew even more forthright in rejecting U.S. intervention. Though he loathed communism, Barks regarded the Vietnam War as an impossible quagmire. A 1966 tale set in the Southeast Asian country of “Unsteadystan” finds the ducks fighting guerrillas, who blow up the Duckburg embassy. It is only when the exiled king returns that the rebellion ends. “We suddenly think it'd be nice for Unsteadystan to have a king again—like in the good old days!” the repenting guerrillas declare as they turn their weapons on the leader of the revolution.Footnote 94 “I tried to turn things back,” explained Barks, in speaking of that story, to “make people think of the better times the people had before they got so damn mad that they were fighting all the time.”Footnote 95 Thus does one of Barks's last stories end in the same manner as the first, with the restoration of a monarchic culture and the strong suggestion that things should be left that way.

What can we make of Carl Barks and his dissent from the era's official culture? This is a particular form of a general question that has come up frequently in the cultural history of U.S. children after World War II. On one hand, it was a time of visible political repression. But on the other, scholars have perceived the rumblings of dissent in the era's pop culture—rumblings that preceded a volcanic eruption in the 1960s and 1970s, as the children born after the Second World War came of age.

The years after the Second World War saw what historians of children and youth have identified as the “reinvention of childhood” in the United States: a rapid and thoroughgoing transformation of nearly all the institutions involved in nurturing children.Footnote 96 This happened in part for demographic reasons—a pronounced reversal of the birth rate's decline that we in hindsight call the “baby boom.”Footnote 97 But children also received new scrutiny because the boomers grew up in the shadow of the Cold War. Other wars in U.S. history had been fought (with exceptions) quickly and on the battlefield.Footnote 98 This war was, on the home front, chiefly a contest of ideologies over a longer duration, to be fought in the classrooms. Cold Warriors cared about winning the next generation and made the beliefs of the young boomers a matter of national security.Footnote 99

The domestic cultural Cold War took many forms. Teachers, activists, and artists faced blacklisting for perceived communist sympathies. At times, repression could approach farce, as when Texan anticommunists sought to purge from their state's textbooks favorable references to the United Nations.Footnote 100 But it was not just a matter of cracking down on purported enemies of freedom. Ann Marie Kordas, Margaret Peacock, and Victoria Grieve have shown how cultural leaders aimed propaganda at children to build a political consensus on issues ranging from economic theory to gender performance.Footnote 101

Yet children rarely sit still for propaganda, and sometimes they seek out unruly stories that challenge adult values.Footnote 102 When scholars have turned away from the literature that parents pushed to the literature that children chose, they have found what Julia Mickenberg has called a “stream of dissent” flowing beneath the frozen surface of “the Cold War consensus.”Footnote 103 Children's culture was an inviting repository for subversive messages, comics especially so. First, comic books’ lowbrow status often allowed their creators to work under the radar, where they enjoyed “vast license,” as David Hajdu has written.Footnote 104 Second, their low prices and widespread availability meant children could buy them directly, without going through adults. And third, as Mickenberg has stressed, comic books and commercial children's books, as opposed to textbooks or films, were too numerous for adults to monitor easily.Footnote 105

Fear of what children chose drove Fredric Wertham's censorship campaign. Yet even after Wertham and his allies succeeded in driving some publishers out of business and removing the most visibly transgressive titles from the newsstand, the comics that remained did not all dutifully toe the line. Scholars have noted the quietly subversive politics of Peanuts (as discussed by Blake Scott Ball), the silver-age mutant superheroes (Robert Genter and Ramzi Fawaz), nuclear-themed comics (Paul Hirsch), and Mad magazine (David Hajdu).Footnote 106 Conflicting and complicated messages, it seems, were a regular part of children's cultural diet.

The big question about the underground “stream of dissent,” in Mickenberg's words, is whether it let out anywhere. Children grow up, and the boomers grew up to throw off many political presumptions with which they had been raised. Did what they read play a role? Mickenberg is intrigued by the fact that many of the 1960s New Left activists had read children's books written by older radicals in the 1940s and 1950s. “It would be impossible (and far too reductive) to draw some kind of cause-and-effect link between childhood reading and the rebellions of the 1960s,” she concedes. Nevertheless, Mickenberg argues, the connections are “not merely coincidental.”Footnote 107 The children's literature must have acted as a “bridge” between generations, even if it is hard to say exactly how.Footnote 108

The same question arises in the case of Barks. Children are time-shifted adults, and the generation that learned to read via the Barks comics became, a decade or two later, the generation that challenged the ideology of modernization head-on. Boomers found modernization uncompelling for numerous reasons, the war in Vietnam and the faltering of the U.S. economy prominent among them. As such factors diminished the ideology's allure, Barks's comics appeared prescient. In 1973, the New Left journal Radical America ran a piece about Donald Duck. The author, Dave Wagner, confessed that he had always assumed Disney characters to be “representative of the worst petit bourgeois tendencies in American popular culture.” Yet, rereading the Barks stories, Wagner saw in them a “biting parody” of capitalism and a “devastating attack on Western imperialism.”Footnote 109

Did reading Barks somehow prepare the baby boomers to reject the ideology of modernization? Mickenberg, in asking a similar question of her own corpus of leftist-authored children's books, hit an evidentiary wall. Yet in this case, we can trace a firmer connection—if not an entirely precise one—between childhood reading and adult politics. What is so methodologically promising about the Barks corpus in this regard is that it was a wildly popular body of work written by a single author with an idiosyncratic voice. Rather than asking whether boomers, as adults, adopted the general political outlook of Carl Barks, we can ask whether they used a distinctively Barksian idiom when doing so.

In Whit Stillman's film The Last Days of Disco (1998), set in the early 1980s, Chloë Sevigny's character, Alice Kinnon, sets out to seduce a thirty-something lawyer, Tom Platt, played by Robert Sean Leonard. Tom shows her his collection of Uncle Scrooge comics and his framed original pages by Carl Barks. “He's considered a bit of a genius,” Tom offers. “There's something really sexy about Scrooge McDuck,” Alice gamely replies. “I love Uncle Scrooge.”

Scrooge's avuncular-yet-pantsless sex appeal aside, Stillman got something right about the early 1980s. Though they had not been published since the 1960s, Barks's comics had an impressive staying power. Barks himself was surprised by how many of his readers, later in life, could quote his work back to him accurately, referencing individual panels on specific pages.Footnote 110 Those now-grown Barks fans also bought his work in new forms. When they bought original production pages, as Tom did, Barks saw no money—he had given those over to his publisher. But Barks discovered that he could offer something similar. And so, for twenty-six years after retiring from comics he supported himself as a painter, depicting the same characters but this time in oils. Barks started out charging less than $200 per painting, but by the end of his life his works were selling at auction for more than $75,000.Footnote 111 It was only in his nineties that Barks finally earned more than a working-class income.Footnote 112

Two rich buyers in particular bid up the prices of Barks originals: Steven Spielberg and George Lucas.Footnote 113 The directors weren't just art collectors. They were fans, members of the generation that had grown up reading Barks. Spielberg appears to have imbibed a healthy dose of Barks growing up. His biographer notes Spielberg's childhood love of Uncle Scrooge comics among such other interests as Disney television shows, dinosaurs, superheroes, and Mad magazine.Footnote 114 The force was stronger with Lucas, who was obsessed with comics as a boy. A friend could obtain unsold issues from the newsstand, and Lucas would sit quietly on that friend's porch, poring over the comics while his friend's family ate dinner. Lucas bought his own comics, too, purchased together with his sister Wendy with their pooled allowances. “We had so many that eventually my dad built a big shed in the back, and there was one room strictly devoted to comics, floor to ceiling,” Wendy recalled. George estimated that the collection contained at least 500 comic books. And his favorite? Scrooge McDuck.Footnote 115

The first piece of art George Lucas ever purchased was a production page from Barks's Uncle Scrooge.Footnote 116 But by that point, in the late 1960s, he had been buying Barks in a different form for a long time. He remembered getting “all the Uncle Scrooge comics I could find at the newsstand” as a child.Footnote 117 “To me, Uncle Scrooge … is a perfect indicator of the American psyche,” he told a reporter on the set of The Empire Strikes Back. “There's so much that is precisely the essence of America about him that it's staggering.”Footnote 118 Cast and crew passed Barks's comics around in the Tunisian desert during the shoot for Star Wars, and Gary Kurtz, that film's producer, published an anthology of Barks's Scrooge stories.Footnote 119 Lucas provided a gushing foreword. “These comics are one of the few things you can point to that say: Like it or not, this is what America is,” he wrote.Footnote 120 As he told Rolling Stone, “Uncle Scrooge swimming around in that money bin is a key to our culture.”Footnote 121

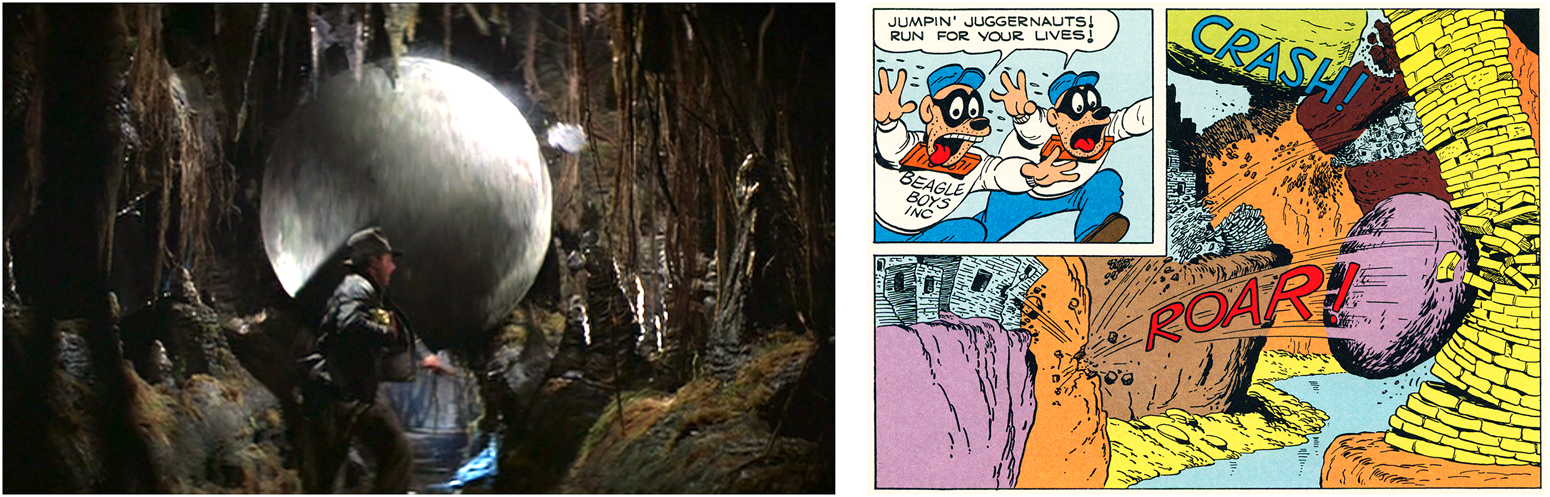

Lucas's and Spielberg's appreciation for Barks was not limited to kind words and bids on paintings. It came out in their films, particularly the three Indiana Jones films of the 1980s, which Lucas conceived and wrote and Spielberg directed: The Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981), Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom (1984), and Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade (1989) (another would appear much later, in 2008). The debts to Barks begin with the famous opening sequence of the first film, in which Jones, while plundering an ancient Latin American temple, takes a small booby-trapped statue of great value and triggers a mechanism that sends a giant boulder rolling at him—exactly the same scenario appears in Barks's “The Seven Cities of Cibola” (Figure 17).Footnote 122 The debts continue through the final scene of the last 1980s film, in which Jones meets a man in medieval armor who has stayed alive for centuries by drinking from the holy grail, which is then lost. Duck aficionados would recognize that as the plot of “That's No Fable”: Scrooge and his family meet a pair of centuries-old men in medieval armor who have kept alive by drinking from the fountain of youth, which is then destroyed.Footnote 123

Figure 17. The famous opening scene from The Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981) in which Indiana Jones outruns a boulder set loose by a booby-trapped statue, was inspired by Barks's “Seven Cities of Cibola,” in which the Beagle Boys outrun a boulder set loose by a booby-trapped statue.

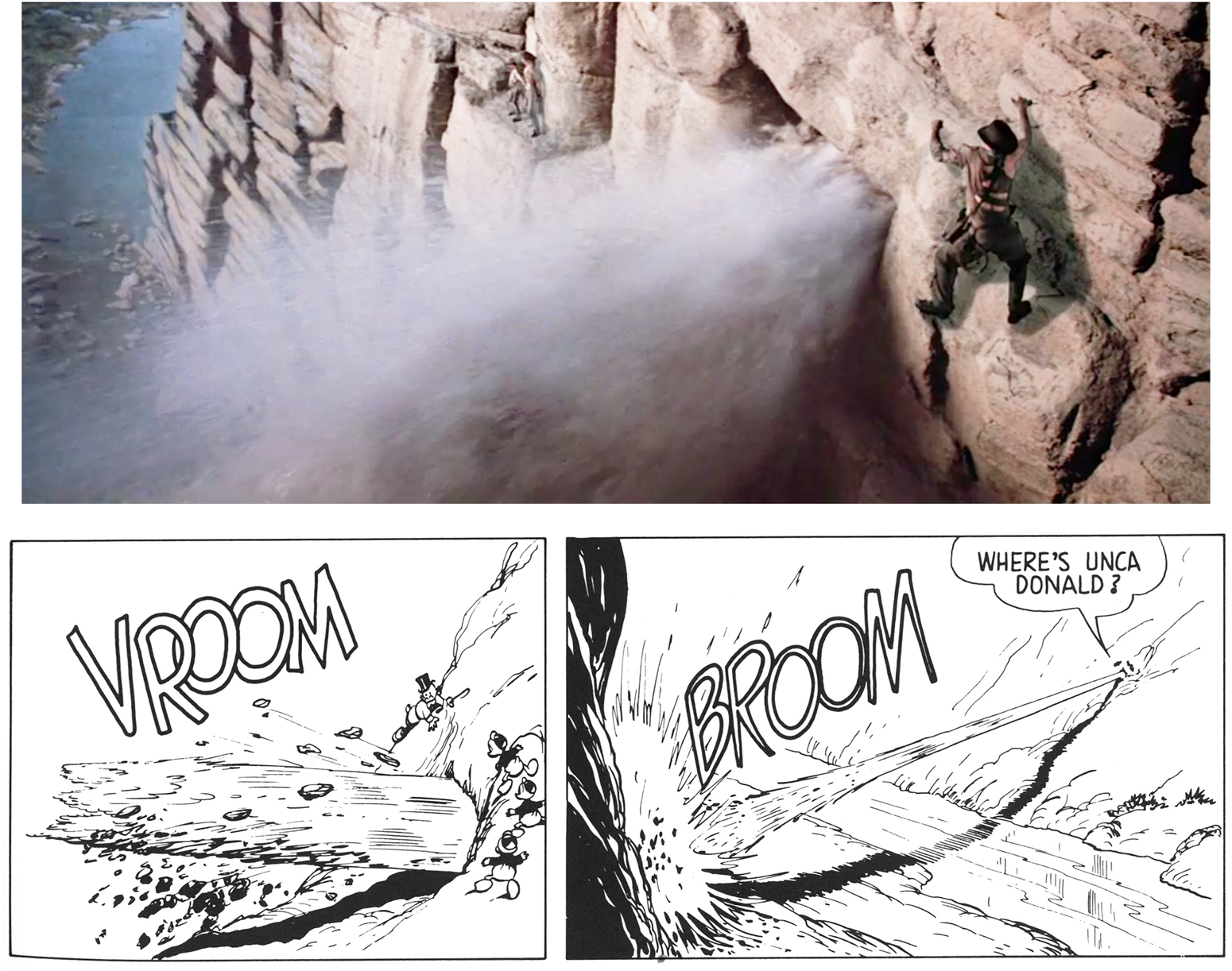

From the start of Raiders to the end of The Last Crusade, the mark of Barks is evident. Indiana Jones finds a battle-hardened lost love in a bar in a cold, remote area; Jones finds an anachronistically traditional society in a cave complex and floods it, sending a jet of water spurting out of a cave entrance; Jones triggers a trap in a tunnel and arrows shoot at him from all sides; Jones sets off a device that sends a giant blade swooping at neck level—replace “Indiana Jones” in these descriptions with “Scrooge McDuck” and you would be recounting Carl Barks stories (Figure 18).Footnote 124 Beyond these plot borrowings, Lucas and Spielberg filled the films with Barks-derived tropes: multigenerational all-male families on archeological quests, precocious child sidekicks in baseball caps, cursed objects, zombie dolls, hidden temples in the jungle, secret catacombs under churches, irate natives wielding bows and arrows, ancient ritual sacrifice, and globe-trotting heroes with distinctive hats.Footnote 125

Figure 18. In fleeing the “guardian of Pankot tradition” in Temple of Doom, Jones and his companions flood an underground complex and barely escape through a cave opening in a cliff face before a spurt of water jets out. Scrooge and his companions flood a similar cave complex, this one occupied by “Royal Guardians” of a centuries-old Peruvian tradition, and make a similar escape in Barks, “Prize of Pizarro.”

More than plots and characters, Spielberg and Lucas offer in the Indiana Jones films a thoroughly Barksian understanding of the Global South. Consider their second film, Temple of Doom. The main storyline commences when Jones visits a traditional village in India whose fields had dried up after the maharajah of Pankot stole its sacred stone. Jones journeys to Pankot and meets its prime minister, Chattar Ali, an erudite Oxford alumnus in a double-breasted suit. At first, Ali seems a perfect icon of modernization, a sort of Jawaharlal Nehru figure whose resemblance to the real Oxford-educated prime minister of postcolonial India is underscored when he appears in the next scene wearing a Nehru jacket. Yet this proves to be a false front. Jones finds a secret passage to an underground cavern, where he reveals the Pankot monarchy to be a Kali-worshipping death cult and Chattar Ali to be a robe-clad, knife-wielding assassin. Jones rescues his companion, a white woman, from ritual sacrifice, escapes, and returns the stone to the village, restoring its agriculture.

Spielberg and Lucas had sought to shoot their film in India. But the Indian government found the plot so offensive that it forbade them (they settled for Sri Lanka).Footnote 126 It is not hard to see why Indian officials objected. Temple of Doom dusts off nearly every colonialist stereotype about India—precisely the sort that had come so easily to Barks. In doing so it rejects the premise of Indian modernization. The bad Indians hew to bad traditions, the good Indians to good ones, but, either way, development is off the table.

Temple of Doom ends as many Barks tales do, with the stone going back to the village. This is a conspicuous feature of the 1980s Indiana Jones trilogy. Ancient societies, artifacts, and spaces are protected or destroyed, but they are never integrated into the modern world. In Raiders, Jones unearths the Ark of the Covenant, which turns out to be “something that man was not meant to disturb” and it ends up re-buried, now in a warehouse. The Last Crusade is a quest for the Holy Grail, which is discovered and then lost again. After Jones returns the sacred stone in Temple of Doom, he is asked why he did not keep it. “Ah, what for?” he shrugs. “They'd just put it in a museum.” It is a recognizably Barksian sentiment, reminiscent of “The Golden Helmet,” in which the ducks discover a centuries-old powerful artifact but, rather than give it to the Duckburg museum, sink it in the ocean.Footnote 127

Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom was, much like The King and I three decades before it, an influential film about the Global South. The two make for a telling comparison. They start the same way, with a visitor arriving at the palace of a traditional Asian kingdom. That they end so differently—with the maharajah reviving a centuries-old death cult rather than singing about science—speaks to an important shift in U.S. popular culture. Modernization was no longer the dominant worldview. In its place, Lucas and Spielberg offered a popular, indelible vision that was highly skeptical of the notion that technology and its fruits would improve foreign societies. Theirs was a world in which Ewoks should be protected, the ancient Jedi order restored, and extraterrestrials sent home.Footnote 128

A variety of antimodernization narratives flourished after the Vietnam War, and not all were Barks-derived. Conan the Barbarian (1982), a dark fantasy about a nomadic Nietzschean muscleman who slaughters effete city-dwellers, is one. The British-made Gandhi, which swept the 1983 Academy Awards, is another. Still, it is telling that the Spielberg and Lucas films were the ones with the most booming resonance. The two directors collectively made the four top-grossing films of the 1970s and 1980s, and eight of the top fifteen.Footnote 129

How much influence Barks had on his millions of readers remains impossible to calculate. Yet the evidence of Lucas and Spielberg is suggestive. It suggests that, for at least part of the baby boom generation, the texts of their childhood mattered. When the dominant ideology of modernization shattered in the 1970s, the boomers were not left without a fallback. They had a counternarrative at the ready, a way of understanding how the United States related to the rest of the world that did not rely on the tenets of modernization. That counternarrative dominated the box office in modernization's wake, carrying Barksian tropes into mainstream adult culture. Understanding children's literature in this way, we can see the 1970s intellectual crisis in developmentalist thought as decades in the making. Modernization had held sway in the midcentury halls of power. But in the children's rooms, the seeds of doubt had been planted, and they were waiting to sprout.