Introduction

In the past decade, Colombia has experienced a surge in tourism. The sector has emerged in a weak institutional and legal setting, leaving space for informal and haphazard processes to surface, which generates dominance and inequity. It is therefore critical to look closely at these developments when addressing issues involving tourism, informality and violence. In this article, I provide a picture of the political economy of tourism and violence in Medellín, Colombia's second city. I examine how criminal actors and tourism entrepreneurs share a territory, shedding light on the extortion of tour guides, street performers and business owners in some of Medellín's barrios populares. The main objective is to demonstrate how intimate relationships – between and among kin, friends, long-term acquaintances – impact the criminal governance of tourism.

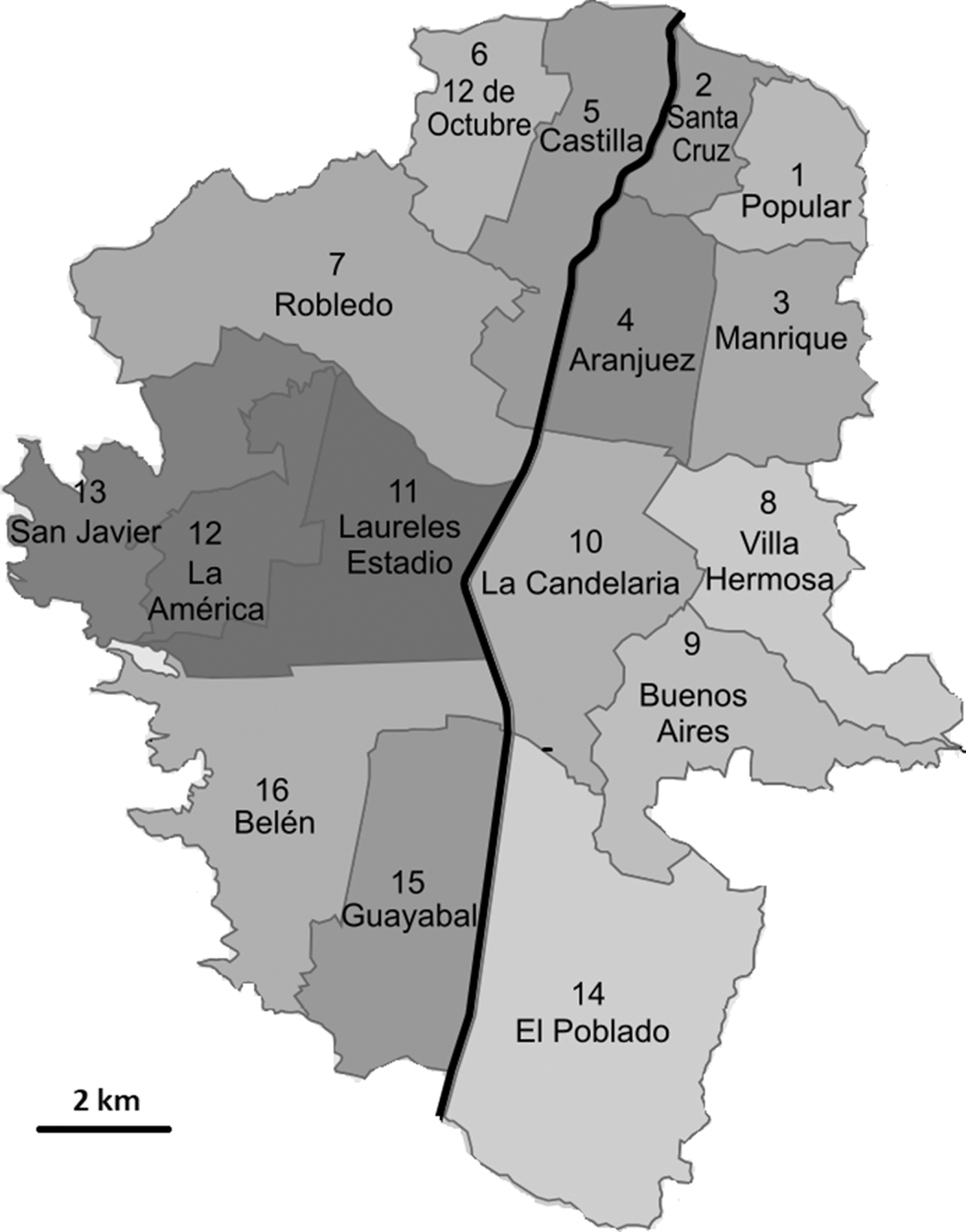

This sector offers an innovative way to consider the economic integration of criminal actors in general. While businesses throughout Colombia have suffered pressures from illegal groups for many years, tourism has become a target only more recently. Taking place in a relatively unregulated setting, the rapid expansion of tourism in Medellín provides a breeding ground for criminal integration. Exploring this process in more detail enables the deconstruction of what is often referred to as ‘the Medellín miracle’ – the transformation of ‘the most violent city’ into ‘the most innovative city’ in the world.Footnote 1 Tourism is an important tool in the diffusion of this triumphalist messaging, and its capture by criminals raises important questions. One of Medellín's peripheral communes provides a significant illustration of the criminal governance of tourism: the violence-ridden Comuna Trece (Commune 13 – see Figures 1 and 2), considered the most militarised zone of the country, has evolved into one of its biggest tourist attractions. Exploration of the criminal governance of tourism in this disputed context allows me to address the practice of extortion in Medellín, another phenomenon that has not yet attracted much academic interest.

Figure 1. Medellín: Communes

Source: Adapted from SajoR, ‘Comunas de Medellín’ (https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Comunas_de_Medell%C3%ADn#/media/Archivo:Comunas_de_Medellin.svg, last accessed 19 Dec. 2022), reproduced under Attribution-ShareAlike 2.5 Generic (CC BY-SA 2.5)

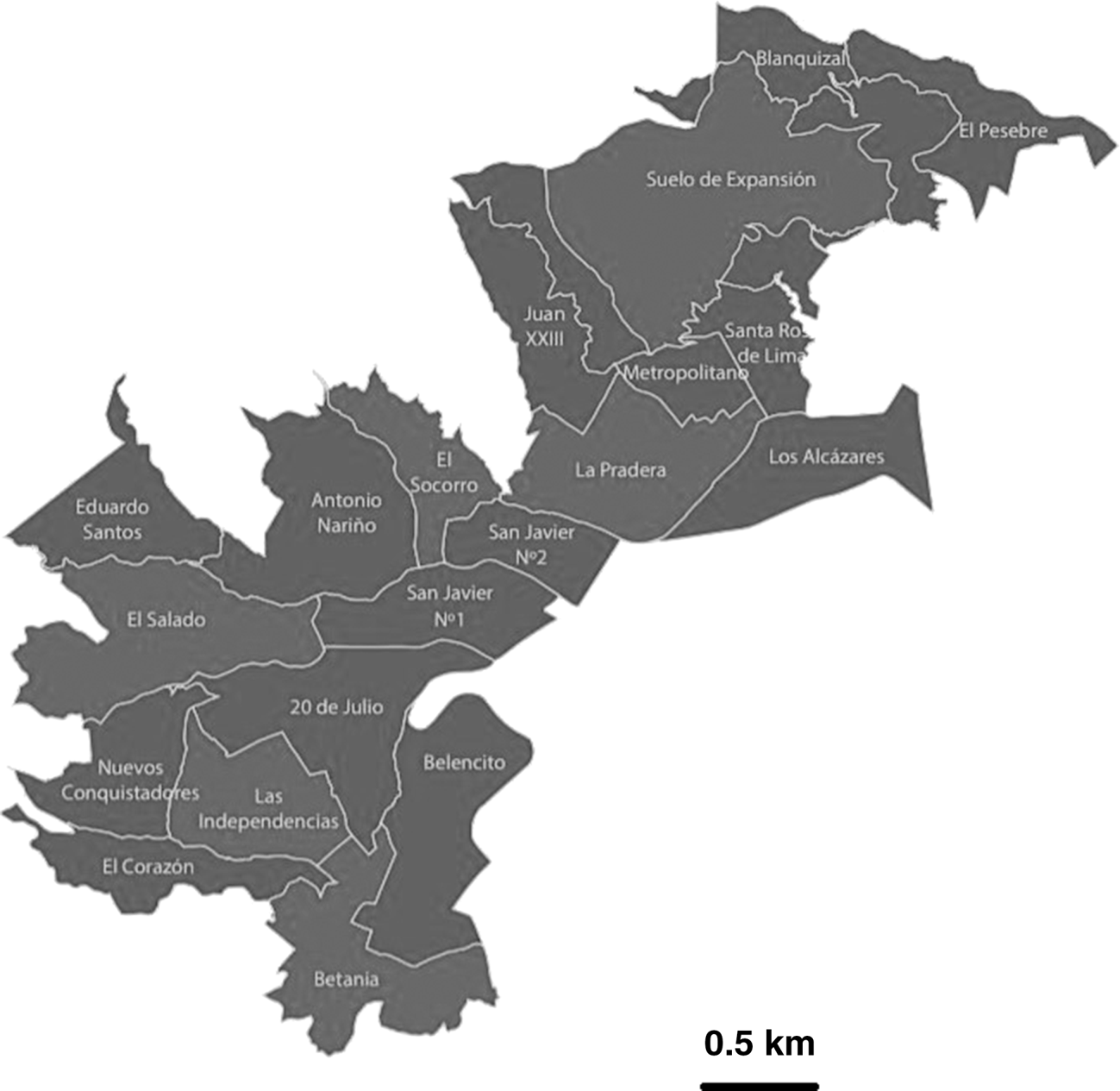

Figure 2. Medellín: Commune 13 (San Javier)

Source: Adapted from Alcaldía de Medellín, ‘Datos generales de Medellín’ (https://www.medellin.gov.co/es/conoce-algunos-datos-generales-de-la-ciudad/, last accessed 19 Dec. 2022)

Some scholars have described criminal governance as a rational, profit-oriented and sometimes even bureaucratic regulatory force,Footnote 2 while others have demonstrated the importance of intimacy in this context. Indeed, at the world's urban margins, where communities are often tightly knit, intimate relationships play a major role in the political organisation of neighbourhoods. Ben Penglase, for instance, conducted an ethnographic study of violence and daily life in a favela of Rio de Janeiro. He introduced the concept of ‘dangerous intimates’, looking at the ways residents and drug traffickers shared friendship and kinship bonds, and how these affected the organisation of this self-built neighbourhood.Footnote 3 As he suggests, violent non-state actors – dangerous intimates – ‘haunt’ these informal areas and are at the same time familiar figures. In Caracas, women negotiated with gang members, many of whom were their sons or nephews, to foster a relative peace. Verónica Zubillaga et al. demonstrated how these negotiations would paradoxically facilitate ceasefires but at the same time perpetuate the dynamics of violence.Footnote 4

Recent scholarship has also explored how criminal groups develop local armed regimes to provide a certain degree of security and social order at the urban margins of Latin America. For example, Jaime Amparo Alves coined the notion of ‘necropolitical governance’,Footnote 5 showing how it generates racialised arrangements of space and contested regimes of citizenship in São Paulo. He describes the dehumanisation of Black citizens, caused by their high level of incarceration and the police-linked death squads that target them, and by the day-to-day discriminations they endure. For Alves, this racialised urban governance is challenged locally by activists and by criminal actors such as the Primeiro Comando da Capital (First Command of the [State] Capital, PCC), which contest ‘the government's fantasies of security and peace through alternative narratives of space and order’.Footnote 6 Accordingly, Enrique Desmond Arias emphasises the importance of neighbourhood-level analysis to fully grasp the various micro-regimes that impact local governance practices.Footnote 7 Exploring criminal governance in Kingston (Jamaica), Rio de Janeiro and Medellín, he demonstrates how communities in informal neighbourhoods, which often see their demands entangled in bureaucracy, seek resources privately, relying on tight local networks and sometimes on criminal actors to improve their conditions. Local armed regimes are thus developed by criminal groups through coercion and cooperation. To maintain informal social contracts with residents, illegal actors such as gangs need to acquire a certain level of legitimacy. As Arias and Nicholas Barnes observed in Brazilian favelas, while these rules are often arbitrarily enforced, the maintenance of public order is nevertheless considered an important benefit and residents generally express ‘little fear of theft or abuse at the hands of neighbors and family members’.Footnote 8

Like Alves, Gabriel Feltran too uses the case of the PCC in São Paulo to illustrate the ambivalence of criminal governance – rational, intertwined with the state, but also with domestic, relational and intimate aspects.Footnote 9 While he demonstrates some of the bureaucratic practices its members adopted and how justice systems were strongly institutionalised, he nonetheless shows the importance of intimate relationships in the PCC's control of the favelas. Beyond the criminal world, intimacy is considered a regulatory construct by Natalie Oswin and Eric Olund,Footnote 10 who see ‘intimate governance’ as a bio-political ‘dispositive’ serving as a primary domain of the ‘microphysics of power’. Oswin and Olund use the term ‘dispositive’ as a literal translation of Michel Foucault's ‘dispositif’ (generally translated as ‘apparatus’): a heterogeneous set of discourses, institutions, architectural arrangements, rules, decisions, measures, scientific or moral statements. In Foucault's view, power is exercised not only in repressive and legal institutions (e.g. law, prison, police); other ‘dispositives’ (e.g. education, sexuality, hospitals) also contribute to domination over individuals within the ‘microphysics of power’.Footnote 11 Thus, ‘governing intimacy’, which is based on ‘[k]inship, procreation, cohabitation, family, sexual relations, love’, is for Oswin and Olund as much a matter of state as it is a matter of the heart.Footnote 12 Adopting this framework in the context of drug trafficking in South Africa and Nicaragua, Steffen Jensen and Dennis Rodgers focus on the importance of kinship, suggesting that the ‘intimate governance of drug dealing’ is not just about domestic arrangements; it ‘produces particular forms of order, often entangled with state and policing governance’.Footnote 13

Hence, by looking at the recent take-over of Medellín's tourism sector by criminal groups, I examine how intimacies produce governance. I suggest that interpersonal ties are critical not only in tourism in general, but also in the way gangs regulate the sector. The framework that I develop below reflects formal understandings of criminal governance, as well as some of the informal processes that contribute to shaping it. In sum, I explore the intimate governance of tourism by gangs, demonstrating how the actors involved, criminals, tourism entrepreneurs, and tourists themselves, participate in the political organisation of the barrios.

As a final point, I reveal how intimacy as a regulatory construct contributes to the production of relationships rooted in domination and inequity. Referring to Ann Laura Stoler, Jensen and Rodgers state that exploring intimate governance does not imply a rejection of structures of dominance, but relocates these processes in the domestic sphere.Footnote 14 In the community fabric, obligations, privileges, clientelism and reciprocity all contribute to shaping the power dynamics of the barrios. As illustrated by Arias and Corinne Davis Rodrigues in Rio de Janeiro, drug traffickers maintain order locally through careful handling of their political, social and emotional relationships with residents. They create what the two scholars see as a ‘myth of personal security’: residents believe they can guarantee their own safety through their personal relationships with traffickers, who as a result would be less likely to punish ‘respected and politically connected residents than those who are marginal to the political life of the favela community’.Footnote 15 For Feltran, these regimes of dominance imply that criminal governance is ultimately like liberal governance, ‘the violent forging of an order suitable to those who hold the reins of power’.Footnote 16

Studying seemingly opposed topics like violence and tourism in Medellín places the researcher in a somewhat paradoxical position. As this study suggests, while tourism spaces are seen as generally safe, they develop in broader environments, often characterised by higher levels of violence. Moreover, while tourism actors in the city aim to shed light on the local history and the cultural heritage of the barrios, the extortion they endure takes place in the shadows.Footnote 17 Based on concealment, it develops into what Dean MacCannell described in his seminal work on the anthropology of tourism as the ‘back region’ – what is supposed to stay behind the scenes.Footnote 18 To understand the dynamics that impact theses touristscapes, scholars thus need to enter the back regions and leave the securitised tourism milieu. This secretive and disputed context poses many challenges for scholars engaged in studies on urban violence, especially those who seek to go beyond desktop research.Footnote 19 Collecting first-hand information implies building trust with individuals who fear possible retribution. In his work on gangs in Medellín, Adam Baird insists on the importance of researchers accumulating local knowledge, socio-cultural competence and a feeling for these ‘rules of the game’. He adds that generating what he calls ‘ethnographic safety’ is possible only once in the field.Footnote 20 Research in a context like Medellín leads some scholars to reflect on their role in these disputed fields, to consider their position between insider and outsider. Luis Felipe Dávila and Caroline Doyle for instance stress the advantages of being an outsider, not only in terms of security and access to informants, but also by having the privilege of leaving in case of trouble.Footnote 21

As a white European male conducting research on Medellín's criminal governance, my own status of outsider implied a certain number of challenges and opportunities, especially in terms of building trust with research participants. This work would certainly not have been possible if I had not had previous experience in the field I was exploring. Long-term contacts, some of them close friends, enabled me to start a snowballing process to access victims of extortion, such as tour guides, artists/performers and business owners. It also meant I could interview former gang members, state officials and community leaders willing to discuss this topic. Previous research in Medellín, begun in 2014, gave me some insights into what several interviewees referred to as ‘the rules of the game’. Furthermore, my status of outsider allowed me to gather information and statements that I would perhaps have been unable to access if I had been more connected to the communities I was researching. Because they viewed me as a foreigner, some of my interlocutors talked more freely; they considered it less risky to do so since I was not directly involved in conflicts taking place in their barrio.

I conducted micro-level research in several neighbourhoods of Medellín controlled by street gangs, some of which were starting to experience the arrival of tourists. This article reflects results gathered in approximately 100 semi-directed interviews, many informal and informative encounters, and content analysis, mainly from the media and social networks. From 2020 onwards, with the travel restrictions due to the Covid-19 pandemic, I carried out interviews virtually with videoconference tools. A research assistant also conducted some dozen interviews, based on an interview grid that we created together. For their security, I refer to all interlocutors by pseudonym and have purposely not identified some locations.

The first section of this article presents recent scholarship on violence and tourism in Colombia. It shows that, despite decades of violence and the significant role of tourism in the current development of the country, studies focusing on tourism and violence in Colombia remain limited. It will then look at the importance of extortion in criminal governance, also pointing out how scarce literature is on this topic, especially concerning the tourism business. The second section describes the research setting, focusing on the take-over of tourism by gangs in certain areas of Medellín. It demonstrates tourism actors’ low level of resistance to extortion. Finally, the last section discusses the importance of intimacy in the criminal governance of tourism, looking at the ways it contributes to a precarious state of security in the barrios, often labelled ‘tense calm’.

A Political Economy of Tourism and Violence

Medellín, Colombia's second city, is a paradigmatic case in scholarship on urban violence. Researchers have mainly approached the topic through studies on security and state formation,Footnote 22 while others have focused on gender, youth or memory work.Footnote 23 Some scholars have looked at the nexus between tourism and peace in Colombia.Footnote 24 The criminal governance of tourism however has so far not been the focus of any studies.

Diana Ojeda has explored the growth of the sector through the lens of state securitisation, suggesting that it was central to the creation of a militarised and securitised space.Footnote 25 Mónica Guasca et al. too have carried out a significant amount of research in Colombia, viewing tourism as a resource for resisting structural violence and defending inhabitants’ livelihoods.Footnote 26 In my own research, I have examined the touristification of violence in Medellín, focusing on the way former narcos moved into the tourism sector, and showing how some of its barrios populares are gradually turning into touristscapes.Footnote 27 In other settings, researchers have explored the relationships between violence and tourism, not only in Brazil's favelas, but also in other regions.Footnote 28 This corpus of research generally focuses on the commodification of poverty and violence, and some have also emphasised how neighbourhoods considered ‘at the margin’ used their bad reputation as a means of forging their identity and international visibility.Footnote 29 Suburbs and urban backyards can offer visitors the perception of ‘securitised danger’, a feeling of marginality where ‘creative populations, bars and boutiques contribute to creating a sense of security’.Footnote 30 Finally, most scholarship converges on the central role of tourism discourses in contestation and resistance, raising issues such as violence, inequity and dispossession.Footnote 31

Hence, more research is needed in Colombia to better understand how tourism can foster peace or in contrast perpetuate violence; how it contributes to the security of cities or increases crime. It must also identify who are the actors in the tourism back regions and what are their goals. This article contributes to this emerging debate by highlighting the tension and resistance that have sprung up in parallel with the touristification of some of Medellín's barrios. Moreover, by looking at the impact of gangs on the tourism sector, this contribution aims at paving the way for further research on how illegal actors participate in creating touristscapes. While Ojeda highlights the importance of the state in the securitisation of places visited by tourists, this contribution will look at the role of tourism actors, criminals, and tourists themselves in this process. Rooted in a neighbourhood-based approach, the objective is to grasp some of the micro-dynamics that shape what has often been referred to as ‘the rules of the game’ in the touristification of Medellín's barrios populares. With its high level of criminal control and the tourism boom experienced in the last decade, much of it developed on gang turfs, Colombia's second city represents a critical case study for such an analysis.

Extortion and Criminal Governance in Medellín

In Medellín's downtown area, as well as in its outskirts, criminal groups ensure some degree of order in the public and private sphere, intervening in petty crime, neighbour-level conflicts and domestic violence. Doyle suggests that residents of Medellín's marginalised neighbourhoods turn to criminal groups because they perceive the state as unable or unwilling to provide them with services such as employment or security.Footnote 32 Gangs thus exploit this weakness to legitimise their control. Yet scholars have demonstrated that the integration of illegal actors in governance is not just the result of a governance void – the abandonment of poor communities by a state generally presented as ‘weak’ or ‘failed’.Footnote 33 Indeed, in Colombia and in Latin America, gangs did not emerge solely in lieu of state institutions: very often, so-called ‘criminal governance’ is the product of a coalition between criminal networks and some of the country's elites.Footnote 34 Furthermore, scholarship on criminal governance generally agrees on the central role of extortion in this context.Footnote 35

In Colombia, the extortion tax is commonly referred to as the ‘vacuna’ (vaccine). Francisco Gutiérrez Sanín and Mauricio Barón trace its origin to the 1980s, when the Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia (Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia, FARC) extorted cattle ranchers, and later sought payment from landlords to avoid being kidnapped.Footnote 36 Looking at extortion in Colombia, Mexico and El Salvador, Eduardo Moncada considers it the purest expression of criminal governance.Footnote 37 He demonstrates the contrasting strategies of resistance it generates, explaining these variations by reference to the political economies of the barrios, the time horizon of illegal actors and the criminal capture of police forces. Anthony W. Fontes offers another important contribution on the topic in an ethnographic study of extortion in Guatemala City.Footnote 38 While Fontes highlights the spectacular violence of extortion in Guatemala, Moncada claims that in Colombia it took the form of unspectacular and everyday victimisation.Footnote 39 Focusing on street vendors in Medellín city centre, he emphasises that their lack of resources in terms of organisation and connections with public authorities lead them to carry out ‘everyday resistance’ (James Scott's term):Footnote 40 negotiating extortion rather than trying to end it. Moncada considers the importance of community ties in these negotiations, showing that criminals and street vendors often share long-time social relationships. Some of them for instance had seen gang members growing up, or knew their parents or relatives, and used these ties to elicit forbearance.Footnote 41 Describing extortion as a brutal form of taxation with little pretence at governance, Fontes nonetheless acknowledges that it constitutes a pivotal social relationship in the communities where it has become entrenched.Footnote 42 In northern India, Lucia Michelutti too highlights how extortion is a socially embedded crime, shaped by webs of reciprocities, mutual obligations, friendships and complicities.Footnote 43

Finally, the nexus between tourism and extortion has so far been addressed only anecdotally. In Sicily, Francesca Forno and Roberta Garibaldi for instance touch on the topic in their study of host–guest relationships in Addiopizzo Travel, a travel agency that organises ‘pizzo-free’ (extortion free) trips centred on restaurants and hotels resisting Mafia extortion.Footnote 44 In the entertainment industry, Peter Gastrow has conducted a study of extortion targeting Cape Town's downtown bars and nightclubs, many of them popular with foreign tourists. He describes how the phenomenon has increased recently, due to the presence of illegal markets and to the lockdown the city lived through during the Covid-19 pandemic, when extortionists’ revenues from other food and drink establishments dried up.Footnote 45 This article contributes to the scholarship on extortion by proposing a case study on tourism, a topic hitherto overlooked.

The Tourism Vacuna

While internal violence has seriously affected the Colombian tourism sector for years, the country saw the arrival of more than 3 million international tourists in 2018, about twice as many as in 2009.Footnote 46 Tourists started to flock to Medellín from 2010 onwards – a phenomenon duly noted by criminal actors. Through their control of micro-territories and the collection of the infamous vacuna, they moved steadily into this lucrative business. Medellín, which was experiencing a real tourism boom before the Covid-19 pandemic, saw a total stoppage of the sector during the lockdown. Tourists returned to the city in large numbers from the end of 2021.

In Medellín, street gangs are usually referred to as ‘combos’: they are tied to a well-defined area (sometimes limited to just one block). However, although the term ‘combo’ is regularly used in the media, my own observations show that city dwellers, particularly in the barrios populares, refer to gangs in many other ways: ‘Los Muchachos’ (The Guys), ‘La Esquina’ (The Street Corner), ‘Los que Mandan’ (The Ones in Charge) or ‘La Vuelta’ (The Business).Footnote 47 With the exception of certain groups which have achieved relative independence, combos are overseen by supra-structures labelled by the public authorities ‘Grupos Delictivos Organizados’ (Organised Crime Groups, GDOs) or ‘Organizaciones Delincuenciales Integradas al Narcotráfico’ (Criminal Organisations Integrated with Drug Trafficking, ODINs). They are also designated ‘Razones’ by some researchers.Footnote 48 While the exact number of these structures is unclear, it is estimated that there are close to 400 combos in Medellín, directed by ten GDOs (according to the city's Secretaría de Seguridad y Convivencia (Department of Security and Coexistence))Footnote 49 or 17 ‘Razones’ (according to Christopher Blattman et al.).Footnote 50 Medellín's combos are usually composed of young males, born in the area and known to the local community. GDOs, on the other hand, are managed by older individuals, often former members of the paramilitary groups who ruled the city's underworld at the beginning of the 2000s. While this is the subject of much discussion, the media and public authorities believe that some GDOs are interconnected, negotiating their share of territory and implementing truces to keep homicides low and business flourishing.

As Blattman et al. have demonstrated, combos in Medellín earn revenues from their monopolies on illegal activities (which take place in so-called plazas de vicio (vice plazas) associated with drugs or prostitution) and in legal markets (e.g. fuel or food). They also make significant profits from the collection of the vacuna and from the local form of loan-sharking (‘gota a gota’, or ‘drop by drop’, with charges levied regularly). They may furthermore engage in other activities, for instance intervening in the resolution of conflicts (e.g. domestic violence or disputes between neighbours) or the policing of public spaces (e.g. prohibiting drunkenness on the street or drug consumption in specific areas).Footnote 51

While the term ‘combo’ generally refers to groups operating in peripheral neighbourhoods of the city, illegal actors controlling the city centre are colloquially designated members of the ‘Convivir’. This label is historically associated with a national cooperative neighbourhood watch programme created in the 1990s before being dismantled due to political pressure.Footnote 52 Historical ties to the paramilitary and the state give the so-called ‘Convivir’ groups some kind of legitimacy: they are now ‘security’ groups which extort businesses, regulate conflicts and control plazas de vicio. Anthropologist Aldo Civico recounted that three years after he was mugged on his first visit to the city centre in 2001, one of his informants, a former paramilitary, explained to him how police and demobilised paramilitaries had worked together to erase petty crime and ‘clean up’ the area, illustrating that paramilitaries, although officially dismantled, were still hand in glove with the state's apparatus of repression.Footnote 53

Medellín's city centre (La Candelaria, Comuna 10) is a major venue for drug-trafficking, prostitution and the trade in stolen goods. But in addition to hosting the main plazas de vicio, the downtown area also has the city's longest association with tourism, mainly due to the renowned Museum of Antioquia and the Plaza Botero, in which 23 sculptures by the eponymous artist are displayed. In 2020, more than 15 years after the mugging related by Civico, a former Asesor de Paz y Convivencia (Peace and Coexistence Advisor) for the city of Medellín explained to me how tourists were protected in the city centre: ‘Not by the police, but La Convivir … I assure you that if someone robs a tourist … they will beat him; take all his belongings; give back everything to the tourist … They may even kill the robber.’Footnote 54 During the previous two decades, (demobilised) paramilitaries displaced (and sometimes even assassinated) members of the marginalised population in Medellín's downtown (e.g. prostitutes, street vendors, recyclers, petty criminals) in a process described as limpieza (cleansing), to justify their carrying out of massacres, selective killings and disappearances.Footnote 55 Perversely, they have contributed to making the area more attractive for tourists and visitors in general. Foreign tourists are increasingly seen visiting the centre. They nevertheless go there mostly during the day, as this downtown area is still considered unsafe at night.

As it grew, tourism became a vector for spreading the image of a transformed city; it was also considered a resource benefitting the poor communities living at its margins. Hence, while the city centre may have the longest association with tourism, the area known as ‘Las Escaleras’ in the peripheral Comuna Trece was the most visited site in the city before the pandemic. ‘Las Escaleras’ are outdoor escalators originally built to improve residents’ mobility in this hilly area. Due to their innovative nature, and also to the surrounding street art, they became one of the most popular tourist attractions in the country. Las Escaleras, as well as the nearby urban cable cars, now feature as the most important symbols of Medellín's social urbanism, a world-acclaimed programme designed to address inequalities by investing in public infrastructure in poor neighbourhoods.Footnote 56 They embody the peaceful reintegration of the state in the barrio, after a decade in which its presence was mainly associated with armed operations. These urban features are now key components in the branding of the city; they also helped put ‘La Trece’ centre-stage in Medellín's growing tourism sector. The outdoor escalators and cable cars draw visitors interested in the city's urban innovations, including urban planners, architects, government representatives, scholars, students and other tourists. The international repute of the comuna was previously raised when Jeihhco and El Perro – two local hip-hop artists – organised ‘Graffitours’ of the surrounding street art, just before the opening of the escalators in 2011.

Following their success, similar tours, in which ‘community tourism’ featured prominently, were organised by a few local guides, several of whom were involved in the comuna's hip-hop scene. The objective was to provide benefits for the residents through the integration of local businesses and the neighbourhood's youth. The success of these tours drew increasing numbers of tourists to the area. According to a municipality census, Las Escaleras and the street art scene of La Trece welcomed 436,395 visitors in 2019, of whom 70 per cent were international tourists.Footnote 57 In 2020, approximately 450 guides were identified in the area by the Red de Turismo (Tourism Network) de la Comuna Trece, a tour guide and business owners’ organisation.Footnote 58 These tours are now widely advertised on websites, on travel forums and in hotels.

Initially community-based, the Graffitours have turned into mass tourism. From 2016, this flourishing market became increasingly managed by external entrepreneurs, reducing barrio residents’ involvement. Some of these new guides were from other neighbourhoods of the city; some came from abroad: Venezuela, Argentina or France. Although many had no connection with the history of the barrio they capitalised on their fluency in foreign languages. Many residents started to criticise the increasing commercialisation of their neighbourhood and what they saw as an appropriation of their collective memory.Footnote 59 Conflicts between tour guides increased and a dramatic drop in tourist numbers due to the pandemic significantly contributed to boosting tensions. Yet, even before the pandemic, many tour guides were already complaining about having their business stolen by outsiders. Fierce competition between tourism actors in La Trece provided a breeding ground for the take-over of the sector by local gangs.

The Rules of the Game

When I started to study the development of tourism around Las Escaleras in 2014, only a dozen guides were offering tours of the area. While some informants associated with the construction of the escalators confirmed the involvement of combos (mainly in the hire of labour and purchase of materials), none of my research participants working in tourism ever mentioned extortion or contacts with illegal groups. It was only during fieldwork in 2019 that I heard the first allusion to what I would then label the ‘tourism vacuna’. Two main factors explain the relatively late integration of criminal actors into this business. First, the international prestige of the site and its importance to the marketing of the city resulted in a significant presence of the state compared to that in other peripheral neighbourhoods. Soon after the escalators became operational, police officers regularly patrolled the area and municipal employees showed up to provide information to the local population, and then to visitors. Secondly, the novelty of tourism in the area and its low initial economic impact also explain the lack of interest from the combos. However, with the intense growth in tourism that followed, the economic prospects were too attractive for criminal actors to stay on the side-lines. Ernesto, a musician performing at the site, commented:

Do you remember when this business started? Most people did not notice it; there were very few guides … But when more guides started to join in, this is when the combos started to see the inflow of money … Another business … And with such demand they realised that they could also take a cut.Footnote 60

At Las Escaleras, tours are based on a specific itinerary, with guides choosing what to present in this high-crime area. The tours generally go into the barrios of Veinte de Julio and Las Independencias, where tourists are led along the escalators. Afterwards, they reach the upper area known as ‘El Viaducto’, a recently built pedestrian walkway overlooking the city, where souvenir shops, artisans’ galleries and street performers abound. Based on residents’ testimonies and data triangulation with former gang leaders, my research suggest that the extortion system is fragmented among micro-territories: various criminal groups are active in the tourist area around the escalators. The combo known as ‘Los del Uno’ controls most of the escalators and the Viaducto at the top, while ‘Los del Dos’ controls the lower area where cars and mini-buses park. Finally, ‘Los del Veinte’ and ‘La Torre’ operate only sporadically in the territory. All come under the authority of the GDO of Robledo (the commune to the north), which dominates large parts of Comuna Trece and defines the territories where these groups can collect the vacuna. The names given to combos and GDOs in Medellín need to be treated with caution. They are often those used by the police and repeated in the media.Footnote 61 As an example, the Robledo GDO is frequently called ‘Los del Pesebre’ by the inhabitants of the comuna (El Pesebre is a barrio in La Trece close to Robledo). Moreover, when tourism actors describe the combos which extort them, they simply refer to ‘Los de arriba’ (Those from above) and ‘Los de abajo’ (Those from below).

The extortion amounts are obviously not fixed sums; they vary depending on the business involved (e.g. a local guide or an external company), the guide himself (e.g. if he has relatives or friends in the combo) or the time of year (e.g. they rise at Christmas and Easter). In 2021, tour guides paid around Col$70,000 per week.Footnote 62 This amount was usually divided between ‘Los de arriba’ (Col$50,000) and ‘Los de abajo’ (Col$20,000). The lower area has many more non-tourist businesses than El Viaducto. The tourism vacuna was therefore lower at the bottom of the escalators, where ‘Los del Dos’ could rely on other income. Most tourism stakeholders in Comuna Trece interviewed for this research emphasised that combo members showed no interest in the content of the tour guides’ presentations. As Ernesto, the musician quoted above, explained: ‘They don't care about the content, they only care about money. They don't care about anybody, they wouldn't care if the world stopped. The only thing they care about is that when someone has to pay, he has to have the money.’Footnote 63

However, while the combos’ involvement in tourism is mostly limited to the extortion of guides, street performers and business owners, they can occasionally participate in the administration of the barrios by, for instance, influencing the distribution of building plots to businesses and intervening in conflicts. In a context of intense competition, Marco, who was one of the first guides to work in the comuna, suggested that the combos could have played a constructive role by regulating the increase in the number of guides:

More than the state, they could have provided a solution to all these guides, all these businesses … They could have controlled that. Right? And that is what business owners usually tell them: ‘I will pay you if you do not let the competition in.’ But what they did was the complete opposite. They said: ‘The more people there are wanting to be guides, the more money we will make.’Footnote 64

This comment sheds light on the main motivation behind the tourism vacuna in Comuna Trece. Extortion taxes are tied to guides, not to the number of tours or tourists. Therefore, the more guides there are, the more combos earn. According to one tour guide, Fernando, a rule was laid down at the beginning of 2021 to prevent guides from doing more than one tour per day. While the intention was to promote an equitable sharing of the market, it brought an increase in guides at a time when there were fewer tourists than before the pandemic. As he said, in the midst of the Covid-19 crisis, competition became unhealthy:

We have an agreement [stating] that each guide is limited to one tour a day. But there are a lot of us guides … There are people who always want more, who do not want to share and who do not understand that everybody needs to work … We did not make this agreement, it was made by the combos. They want to charge everybody. They do not want to charge the vacuna at the end of the week and be told that they [the guides] could not work.Footnote 65

Fernando added however that there was some flexibility in the rule, especially since guides hired by an external company would generally refer combo members to their employer for the payment of the vacuna:

I did three tours in one day. I was criticised by everybody and of course someone went to talk to ‘Los de la Vuelta’. In the afternoon – after I finished the tours – they caught up with me and asked me about it. I had to show them the messages and chats [to prove to them] I was a third party … I had a booking [from an outside tour company] so I could do it. I was not en la esquina (on the street corner) grabbing the tourists and taking away an opportunity from a compañero. Footnote 66

Extortion and Resistance

Interviews with tourism actors revealed that very few of them resisted the vacuna. The main reason is obviously the risk involved, which can lead to a severe beating, the loss of business, forced displacement or even death. Furthermore, the very low expectations of seeing any official intervention against a widespread practice like extortion seriously discourage any form of resistance. Tourism entrepreneurs described the various levels of intimidation they were subjected to, ranging from repeated damage to their property to physical attacks. Ernesto for instance related how members of the combo would occupy the spot where he and his band were to perform hip-hop shows. The musician explained that they prevented his band from earning money by discouraging tourists from watching their performance and redirecting guides to other parts of El Viaducto. Tensions eventually resulted in a confrontation: ‘In the middle of the dispute, one of them took out a 38 [calibre] gun and threatened us. He said that he was el que mandaba (the one in charge); that we were going to pay or that he would kill all of us.’Footnote 67

The relatively low level of the vacuna compared to the money tourism brings in is another reason for the weak resistance to extortion. A guide usually charges tourists Col$30,000 for a tour, and some guides explained that on a good day they could earn around Col$300,000. The vacuna was thus considered a low cut. As Fernando put it, the risk of being at best expelled from the barrio or at worst killed was not worth it: ‘For what? Col$40,000? I make a lot more than this in a week so I pay it without any problem.’Footnote 68

Some comments even implied a favourable view of this illegal practice, compared to official taxes. Combos were portrayed as funcionarios del barrio (barrio officials) or compared to a bank: ‘The bank also charges me a vacuna every time I go to the cash dispenser. Their vacuna is legal and this other one is illegal.’Footnote 69 The tourism company owner who made this comment also explained how he was charged the vacuna for the five guides he was hiring and how he would negotiate: ‘I need to befriend them and negotiate: “¡Dale Papy! (Come on, man!) Reduce it because it is very expensive!”’Footnote 70 Several interviewees had a similarly humorous view of the practice, as the comment of this shop owner selling pipes for smoking cannabis illustrates: ‘One of them who was selling products [drugs] was interested in my goods and laughed: “When you need to fill them up you know where to go!”’Footnote 71 Some tourism actors also commented positively on the fact that after the pandemic started the vacuna was demanded less frequently. The comparison of the vacuna to legal taxes associated with banks or the state demonstrates a lack of trust in these institutions. The fact that, with the growth of the sector, tourism profits were increasingly being redirected outside the comuna – for instance into the pockets of external tour operators – came in for frequent criticism. As devil's advocate, I could argue that the contribution to illegal but local groups can be considered as a form of ‘community tourism’. While I am well aware that most of the illegal profits do not remain in the barrio, some of the comments above suggest that, in some part of the local imaginary, paying a tax to the local combo, run by muchachos who are often well known in the community, is seen as a lesser evil than giving money to legal – but external – institutions.

Some tour guides also questioned the effect of public criticism of the combos, stating that it made them more aggressive. Sabrina criticised a particular accusation: ‘He made it on social networks and also on the television news, and all this impacted us negatively: those who charged us became more gruñones (grumpy).’Footnote 72 She added that, in the following weeks, combos became even stricter about the payment of the vacuna. In her view, the police would never intervene as they were in collusion with criminal actors; in the end, the impact of public criticism would only be negative for the rest of the guides. Jason, another tour guide, commented on the importance of not opposing the dynamics of these territories, but of trying to change them in the long term: ‘The dynamics in the barrios can be very strong and you don't know who is who. One thing that characterises [our company] is that we are friends with everybody, young and old, businesses, with la esquina (the gang) … everyone.’Footnote 73 My research has nevertheless revealed that at least two organisations have decided to stop their tours, as they did not want to contribute to the profits of criminal groups. As Eda, a member of one of these organisations, explained, paying the vacuna would have meant giving money to the extortionists: ‘It would be giving money to those things that we are trying to transform in the comuna – drug trafficking, violence – so we were definitely not prepared to give them money … no way!’Footnote 74 It is important to specify that both these organisations were offering tours in parallel with their main activities, which was art and memory work. The fact that they were not entirely reliant on tourism might in part explain their decision.

The (Intimate) Governance of Tourism

In Medellín, the informal development of tourism in the barrios illustrates what Moncada considers to be an ‘atomized political economy’. Tourism actors are evolving in a context characterised by a lack of organisational structures, both amongst themselves and with the official authorities.Footnote 75 Moreover, some of my interlocutors suggested that police forces were working hand in hand with the combos controlling tourism. Like the street vendors in Medellín described by Moncada, tourism actors lack the resources that would enable them to mobilise and resist collectively. They can resort only to ‘everyday resistance’: they do not try to oppose the payment of the vacuna, but they occasionally negotiate its amount. Yet, in contrast to street vendors, many tourism actors seem to consider what they earn as high enough to tolerate extortion. The cost-benefit of the tourism vacuna is often seen as acceptable.

Some examples in my research demonstrate a rational dimension to gang control. Even if the tourism vacuna is not set in stone and extortion practices sometimes appear haphazard, statements nevertheless suggested a relative consistency in the level and collection of the fee. Other accounts – as reported above – indicate that tour guides could for instance present evidence of working for a third party (who would then pay the vacuna), a process that was accepted by combos. Moreover, the perception of criminal actors as funcionarios del barrio suggests that the practice of extortion is in some way viewed as an administrative procedure.

Describing tourism's illegal governance as taking place solely in a rational framework, however, does not present the whole picture. As in Moncada's study, where street vendors use personal relationships and shared social histories with their extortionists to negotiate the vacuna, several interviewees similarly emphasised how kinship and friendship could influence the way combos manage extortion, resolve conflicts or distribute resources. A store owner in La Trece explained for instance how his family ties enabled him to avoid paying the vacuna: ‘A lot of people from here and integrantes del combo (gang members) were kids that my mother taught while she was a school teacher. I see that as a kind of gratitude toward her.’Footnote 76 As this comment suggests, residents in the barrios populares, whether or not involved in illegality, have often shared ties for generations; they have common experiences in the street, in their family or at school. Clearly, intimate relationships contribute to shaping the rules of the game in the barrio. In the tourism business, some interviewees for instance mentioned bans on organising tours where tension existed with the relatives of a combo member. Others commented on the stress this could generate:

They came – ‘Los de arriba’ and ‘Los de abajo’: ‘Any problems you have, just tell us.’ So [I told them,] ‘ … I have a problem with this guide because she stole a tour from me. Call her and fine her.’ But all you get is a ‘No’, because the guide is the girlfriend of a pelado de la vuelta (guy in the gang).Footnote 77

The founder of a tourist attraction in Comuna Trece, who had to pay the equivalent of several thousand dollars to the local combo in order to start his business, underlined how residents shared close ties with criminal actors. For him, it was therefore impossible to escape them. Moreover, as he had known several of them for years, he felt even more obliged to offer them a discount:

Many of them are friends or acquaintances. If someone tells me he has no relationships with the combo, he is lying. For instance, recently, people from the combo came and asked to [use the facilities]. I could not let them in for free, but I charged them half-price.Footnote 78

Following the success of tourism around Las Escaleras, other barrios populares capitalised on their troubled past and their creativity in order to attract tourists. Moravia (Comuna 4), Santo Domingo (Comuna 1) and Barrio Pablo Escobar (Comuna 9),Footnote 79 among others, began seeing an influx of tourists before the pandemic, albeit in limited numbers. Illegal actors were also implicated in the control of these micro-territories, where tourism was blossoming. A discussion I have partly transcribed below provides another illustration of the tensions that arise when gangs and tourism entrepreneurs share the same turf.

Lucho is the son of a duro (gang lord) in a barrio which began seeing the development of guided tours as of 2019. He considers his whole family to be profesionales de manejar la vuelta (gang management professionals): ‘When they killed my grandma's eldest son, my family was very big, with a lot of men. So they set up a combo and shot those who did not like us.’ While he does not claim to be a member of the combo, he is involved in several illegal activities. He explained he liked taking care of the barrio: ‘Even as a “nobody”, I watch out for the barrio. I don't like thieves and bandits.’Footnote 80 Indeed, on several occasions I saw him impose order when we were strolling together in the streets (for instance censuring kids who were smoking cripa (marijuana) in a ‘smoke-free area’). In the lines below, he shares with William, a community leader, a negative experience he had with a group of foreign visitors and their guide.

Lucho: There were like 15 Mexicans with gringos, all revueltos (mixed), with cameras de loco (of madmen), cameras of 20 or 30 million pesos. And there were three other foreigners. There were all botados (lost) over there … So I asked them who their guide was.

William: Sure! Because when we [bring foreigners], if we go into a place, as community leaders, we know that esa vuelta (that gang) is working here. So we tell people: ‘Keep your cameras and phones out of sight, they don't like that here.’ ¡Mijo! (Hey, son!) Over there they could really have been mugged! ¡Ciao! (Jeez!)

Lucho: ¡Ciao! She [the guide] misinterprets everything I said. It's not something that the muchachos told me to do, like to conspire or something … I told them: ‘Come with me to avoid getting mugged. You give me 20 or 30 thousand and I will walk with you.’ I told her [the guide]: ‘You need to be more careful. If you are going there with so many foreigners at least involve the community, guys of the barrio, to protect you.’Footnote 81

In the view of Lucho and William, the mugging of foreigners was very unlikely in this area as long as you knew where you were going, and especially if the combo did too. Lucho added that thieves from outside often came into the barrio. They did not have the same respect for the place as the residents and were therefore unconcerned about committing crimes. Hence, if the combo was not aware of the tourists’ presence, it could not intervene if visitors were robbed by outsiders. Moreover, due to his family ties, Lucho's contribution to the debate on tourism development was viewed by the guide and other residents as an attempt to provide ‘protection’ from his family:

They then made such a fuss [polémica] about it! … I didn't give you my opinion so that you would make a deal with the muchachos or private security to walk around with them [the tourists]. I just said that if they [the guides] came into the barrio with a lot of tourists, at least they needed to make sure that they all stayed together!Footnote 82

This controversy shows how Lucho's family context shaped his relationships with entrepreneurs building a new touristscape. While Lucho insisted on his non-affiliation to his family combo, his family status nevertheless led him to intervene in the tourism development of his barrio. His knowledge of the area – and especially his fine understanding of the rules of the game – meant he could criticise wannabe tour guides for what he considered inappropriate behaviour. Indeed, while tour guides in La Trece stick to a well-known itinerary and have a good understanding of the rules, in other neighbourhoods, where tourism is emerging, tourism actors are navigating in murky waters.

These examples shed light on the challenges inherent in the development of tourism in informal urban contexts partly governed by illegal actors and where the role of public bodies is often dubious. Despite triumphalist public discourse on social urbanism, some of it in the tourism sector, the state's presence in Medellín's barrios populares, and particularly in Comuna Trece, is still associated more with repression than with social support. While municipal programmes in Comuna Trece aiming to empower local youth through art and tourism have existed for several years, the training of guides is very recent and poorly managed. Potential tour guides are required to follow a training course from the Servicio Nacional de Aprendizaje (National Apprenticeship Service, SENA) in order to be certified. In reality guides are rarely checked up on and most are not officially recognised. Recently, some collectives offering tourism activities have decided to train their own guides independently.

Although tourism around Las Escaleras tops the promotional agenda of the city, regulation of the sector is precarious. Apart from shiny websites and catchy slogans promoting the site, the infrastructure remains very weak. Moreover, actors directly or indirectly associated with the tourism sector do not see the state providing any form of protection or any means of conflict resolution. Nowadays, apart from the SENA training course, the only other institutional ties between the city authorities and the guides are to be found in the Red de Turismo de la Comuna Trece. However, this network is struggling to unite all these actors within its organisation, as many of them prefer to work autonomously. In this atomised political economy, reliance on combos may well appear a pragmatic solution, especially when the vacuna is seen as a small take from a flourishing business. While my research tends to demonstrate a fairly low resistance to extortion, many interviewees were nevertheless very critical of this situation and pessimistic about the future. During the pandemic, the founder of the tourist attraction mentioned above was not optimistic about the development of tourism in La Trece: ‘Guides are threatened; they are fighting each other with knives. It is starting to be a big problem, so a lot of companies do not want to come back … because of this and because of the extortion. If nothing is done now, tourism will come to an end.’Footnote 83

This last comment sums up the wide concern at the lack of adequate governance in the tourism sector. In those Medellín touristscapes where governance mechanisms are present, they often reproduce social injustice through a neoliberal process, ‘exploiting rather than exposing injustice’.Footnote 84 The example of tourism demonstrates that, when combos rule, clientelism and privileges due to kinship and friendship often determine the outcome of conflict resolution. My research partly confirms what Arias and Rodrigues identified in their conception of a ‘myth of personal security’. Reflecting their description of traffickers’ governance in Rio de Janeiro, Medellín's combos tend to favour the interests of respected and well-connected residents over those on the margins of the political life of the barrio. Aligned with Oswin and Olund's concept of intimate governance, the organisation of the tourism sector is critically influenced by interpersonal relations. As a ‘dispositive’, intimate and criminal governance shapes how power is organised and exercised. Tourism development in Medellín's barrios takes place within the ‘microphysics of power’, where favours and debts often generate inequity and dominance.

‘Tense Calm’ and Tourists’ Security

Some scholars working on extortion have stressed how criminal governance could paradoxically help to foster a certain level of security.Footnote 85 For instance, when Moncada observes resistance to extortion by informal vendors in Medellín, he shows that some of them welcome protection because of the high level of crime in the city centre.Footnote 86 Echoing the argument I described above between Lucho and a tour guide, illustrating the importance of keeping tourists safe, several examples in my research highlight how tourism entrepreneurs and illegal actors, as well as tourists themselves, contribute to the security of the barrio. The discussion I had with Juan in 2019, shortly after he decided to end his criminal career and leave ‘Los del Veinte’, illustrates a common assumption that the barrios populares are safer than wealthy areas of town. As in Arias and Rodrigues’ account of the favela, the barrio, often seen as dangerous by outsiders, is considered by its residents a safe place:

Juan: [The goal] is integration between people; avoiding problems between them; so that everybody lives well together; so that people can go out any time they want … Nowadays, you are more likely to be robbed in El Poblado than here.Footnote 87

Author: So I can wander about safely, even as a mono?Footnote 88

Juan: If you want … and [even] if you have a gold chain or a watch … you enter, leave, come back. They [the combos] will watch out for you.Footnote 89

For several interviewees in Medellín, the tourism vacuna contributes to the safety of visitors in former no-go zones; it therefore facilitates their work as tour guides, performers or shop-owners. As an art gallery owner summed up:

I do not see it as something bad, but more like a win–win. Qué chimba (It would be great) if this did not exist, right? But I don't want to kill myself thinking: ‘What to do?’ It is something that exists and I know in what kind of place I live … the history it has. So it is just another business expense … I feel secure, I feel good. We had misunderstandings with some people and they helped us resolve the problem.Footnote 90

Several interviewees however compared the barrios populares in Medellín to ‘powder kegs’ or ‘sleeping lions’, which might explode or wake up at any time. Indeed, Comuna Trece is an unfortunate example of this volatility: several waves of homicides have occurred in the barrios of La Trece in the last decade. They usually lead to a large and temporary presence of public forces in the comuna. In February 2020, seven homicides (six in 48 hours) occurred about one kilometre away from Las Escaleras. They were attributed to a confrontation between ‘La Agonía’ and ‘Las Peñitas’. The clash between these two combos spurred the deployment of approximately 300 members of the police and military forces and led to the arrest of 47 members of ‘La Agonía’.Footnote 91 These homicides went unnoticed by the tourists who were visiting the comuna at the time, but they significantly impacted the dynamics of the territory: anxiety tied to the prospect of more shootings increased in the community; messages from criminal groups popped up on residents’ WhatsApp groups, with orders to avoid specific streets; police forces accompanied children to school the following week; combo members disappeared from street corners, fearing arrest.

As some scholars have observed, this climate of mistrust and precarious security is known in Colombia as ‘calma tensa’ (tense calm): ‘the psychological grip generated by fear that gangs held over the community’.Footnote 92 ‘Tense calm’ resonates in the words of Armando, a Comuna Trece performer, who commented on the status of tourists in this context:

There is always the fear of [a confrontation with] ‘Los de la Torre’ (Those from the Tower), ‘Los de la Sexta’ (Those from the Sixth [Street]) or ‘Los de la Terminal’ (Those from the Terminal) … There is some rivalry, but there can't be war, now that tourists and people from other parts of the world are present. If a foreigner were to die the problem would be gravísimo (extremely serious), so there is a truce.Footnote 93

As my research illustrates, intimacy in strongly knit communities represents an important regulatory dynamic in tourism entrepreneurs’ practices. Armando's comment, however, suggests that community outsiders – tourists and foreigners – also participate in fostering security. He implies that the presence of international tourists contributes to the absence of violence, or at least limits visible acts of violence. His vision presents foreigners as untouchables, whose presence contributes to the (tense) calm of the barrio.

Similarly, ‘international accompaniers’ use their outsider status as ‘unarmed bodyguards’ to provide security to social leaders during risky journeys in Colombia. As Sara Koopman puts it, they are ‘less likely to be attacked because … their passports make their lives “worth more”’.Footnote 94 Like the ‘international accompaniers’, tourists in Medellín too seem to contribute to the security of the place, albeit unwittingly. Several interlocutors for instance linked the need for tourists’ security with the city's miraculous transformation, suggesting that everyone benefitted from their presence. In their view, public authorities, private bodies and illegal groups’ objectives merged when the goal was to increase foreign investment and tourism. Meanwhile, inhabitants on the margins remain ‘hostage to pervasive systems of fear’ or calma tensa. Footnote 95 Medellín's tourism vacuna also contrasts with the spectacular brutality described by Fontes in the context of extortion in Guatemala, where the gangs’ business models thrive on expressions of violence circulating in the community and the press. According to Fontes, the ‘smoothness’ of extortion works only in spaces where control over the use of violence has been established.Footnote 96 Tourism entrepreneurs in Medellín are similarly dependent on the calma tensa that characterises some of its comunas and facilitates the ‘smooth’ running of the tourism sector.

Finally, while the presence of tourists contributes to security, it is not without tensions. The following contrasting statements show some of the disputed representations that the touristification of Medellín's periphery generates. The first is from a tour guide who suggested building a hotel in Comuna Trece. The second is from a community leader who presented a critical view of tourists in the comuna:

Tour guide: [Tourists] would be able to experience playing football with the kids of the barrio; experience talking with business owners. It is a lot stronger than if you were staying in La 70 (a street known for its nightlife) or in El Poblado, because you will have contact with real people. We want this experience to be more than a hotel, an experience where people would say: ‘Wow! I was in Comuna Trece.’ And at any moment anything can happen …Footnote 97

Community leader: Tourists find this more interesting! ‘I am not only smoking weed, I am smoking it in Comuna Trece …’ Plus the danger that a shooting can happen. I see these tourists coming here completely unaware [of the dangers they expose themselves to].Footnote 98

In the first comment, Medellín's reputation as a ‘powder keg’ contributes to the tourism experience. Calma tensa, the possibility of an outburst of violence, is presented by the guide as an added value, a consideration that, in contrast, is seen as offensive by the second interlocutor, who has no connection with the tourism sector. Calma tensa is part of the buzz of a visit to La Trece, and seems to flourish in a context of ‘securitised danger’. This phenomenon is criticised by some as being a form of commodification and glamorisation of violence and illegality. The comment of the first interlocutor should nevertheless be seen as more than a simple presentation of violent exoticism. What is really offered to tourists in this hotel project is once again intimacy, a component of foremost importance in the tourism encounter. In his reflection on the tourism back regions, MacCannell suggested that intimacy and closeness with locals led some tourists to feel morally superior, more ‘real’: ‘Being “one of them”, or at one with “them”, means, in part, being permitted to share back regions with “them”.’Footnote 99 When the interviewee quoted above explained his desire to build a hotel in Comuna Trece, he highlighted the attraction for tourists of being with ‘real people’. However, when the ‘back region’ includes violence and extortion, taking tourists behind the scenes can be a source of tensions. Yet again, allowing tourists to explore the back region may give them more accurate insights into what it means to live on the margins of a city in Latin America.

Conclusion

In Medellín, the practice of extortion arouses little resistance among tourism entrepreneurs. They may attempt to lower the tourism vacuna, but generally do not try to stop it. Extortion is also well controlled: each combo has an assigned territory and none of the tourism actors interviewed suggested that they were simultaneously charged by rival gangs. Furthermore, some of them felt that the tourism vacuna contributed to their security, and even more to that of the tourists, who were not subjected to extortion.

This research contributes to scholarship on the unspectacular violence of extortion in Colombia's political economies by examining the role of intimacy in this context. Focusing on the micro-dynamics operating in a web of relationships between gangs and tourism entrepreneurs, I have emphasised the importance of interpersonal relationships in the criminal governance of tourism. As Oswin and Olund state, intimacy is personal. It is also, therefore, political. Intimate governance provides an effective tool for understanding who is vulnerable, and who is not.Footnote 100 On a spectrum ranging from community insiders to outsiders, it shows the status of various actors in this process. While some individuals who are well connected within the social fabric of the barrio might earn more privileges and respect from gangs than others, outsiders like tourists are considered untouchable. They are highly protected, in contrast to some city dwellers on the margins, who are condemned to live in a permanent state of calma tensa.

In this analysis I have also attempted to deconstruct some well-worn and preconceived ideas associated with Medellín's transformation, particularly in the space known as Las Escaleras. The tourism boom has undeniably brought some business opportunities for the community, but at the same time it handed many others to criminal groups. Behind the well-polished image of Medellín's miracle propagated by the tourism sector, a situation of profound inequity and severe violence prevails. Medellín illustrates a paradox, where tourism brings socio-economic resources to peripheral neighbourhoods, but at the same time participates in the victimisation of their residents. In La Trece, for instance, tourism initially had a political message, highlighting the roots of the violence in the area. However, in the long run it has empowered the criminal structures it was criticising. These micro-dynamics taking place in the shadows, like the mundane violence of extortion, demonstrate that, despite its miraculous transformation, Medellín still faces many challenges. Beyond the spectacular violence of homicides, inhabitants in its barrios populares struggle with everyday issues like extortion, domestic violence, threats and vandalism. Social and urban innovations heavily promoted by the municipality and the private sector have certainly contributed to a decrease in homicides in the last two decades. Yet, as this study shows, criminal actors demonstrated innovative skills when they moved into the lucrative business of tourism.

Finally, I hope that this conceptual analysis of criminal governance will lead to further interpretations of this phenomenon, beyond tourism, Medellín and Colombia. That being said, more attention should be paid to Medellín itself. While a large part of the testimonies presented in this article were collected in Comuna Trece, tourism is also growing in other peripheral areas of the city. The dynamics observed in La Trece can shed some light on the consequences of tourism development in urban areas that have lived with – and continue to live with – intense violence. While many hope for a prompt recovery of tourism in Colombia, now is certainly an opportune time to explore its recent and intense growth, in order to understand some of the pitfalls. My research seeks to advance this debate in Colombia and elsewhere, and to stimulate further reflections on the role of violence, informality and intimacy in this sector. By emphasising some of the power-laden relationships embedded in the practices generated by violence and tourism, I call for more studies on these seemingly unrelated topics. When tourism develops in contexts where crime lingers, it can provide resources for local communities, but it can also exacerbate their victimisation and perpetuate violence.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Prof. Dennis Rodgers for reading the first draft of this article and for his constructive comments, as well as the three anonymous referees for their pertinent suggestions.