Introduction

On International Workers’ Day 1961 the International Labour Exhibition (ILE) opened in Turin. The exhibition, with the title ‘Man at Work: A Hundred Years of Technical and Social Development: Achievements and Prospects’, was part of the festivities celebrating the centenary of the unification of Italy across the country. It also, as this article reveals, became a site of high-level cultural diplomacy where participating countries from across the political divide made claims about the superiority of their labour policies and the social security they offered. These claims were evidenced by examples of modern design and architecture, which each state employed not only as a means to communicate their ideas about social provision but also to conceptualise and substantiate them.

The ILE attracted the attention of the editors of the leading Italian design periodical, Casabella-continuity (Casabella-continuità), who made it the feature subject of their June 1961 issue. The opening article, written by the magazine's editor-in-chief, Ernesto Nathan Rogers, examined the exhibition through the lens of the historical legacy of the Risorgimento.Footnote 1 In Rogers’ opinion, the exhibition revealed the fundamental ‘national error’ that modern Italy was facing – social inequality. In his passionate critique he pointed out that despite the ‘Italian miracle’, the country had failed to resolve the pressing issues of public education, housing, healthcare and transport. Design had been an essential part of the country's post-war success, and Rogers contended that it should have been employed to improve the lives of the Italian population. The state, however, showed no interest in harnessing the power of Italian design – which at the time was at the height of its international acclaim – to solve the domestic problems of working people. In Rogers’ opinion, this negligence, as the Italian section of the ILE revealed, attested to the Italian state's lack of social commitment: the authorities used design merely as scenography, which, although at times brilliant, obscured the country's very real social problems.

The ILE also featured in the Polish design magazine Projekt, published at roughly the same time. In various articles authors outlined the historical alliances between Poland and Italy, explained the foundations of modern Italian history and introduced the ILE to a domestic audience, with a clear focus on Poland's participation. One of the articles, written by a prolific cultural commentator, Jerzy Olkiewicz, framed the Polish display as a demonstration of the social commitment of the Polish state. Explaining the narrative of the Polish exhibition, he stated that:

The social theme of the exhibition is linked directly with architecture – through the construction of modern industrial halls, sanatoria, hospitals, clinics, nurseries, schools or aged care homes – and indirectly with art, which is manifested in its focus on the purposeful and artistically interesting design of the interiors of newly built facilities.Footnote 2

Although Polish design and architecture had much less currency internationally than those of the Italian hosts, the exhibition in Turin, as Olkiewicz boldly argued, was devised to demonstrate the Polish state's deployment of design and architecture for the benefit of the entire society.

This article examines the premises of this declaration by addressing both the content and the form of the Polish exhibit and by discussing it in the broader context of cultural diplomacy. The text advances the debate about the latter in two ways. First, by using the example of People's Poland, it demonstrates that countries were positioned in competition with each other not only in terms of technology, individual consumption and societal values, but also in terms of their approach to social issues. In doing this, the article contributes with the original case study to the scholarship that has expanded the framework within which international exhibitions have traditionally been studied.Footnote 3 Second, by highlighting the importance of designers as non-governmental stakeholders in the process of forming a favourable image of the nation abroad, this article contributes to the burgeoning scholarship on design diplomacy, a specific category of cultural diplomacy.Footnote 4 It reconstructs the rationale and the design of the Polish ILE exhibit and provides an interpretation based on archival material and supported by the existing literature in design history, exhibition studies and Cold War history. An important caveat should be placed here: the archival material documenting the Polish exhibition in Turin is extremely scarce. The New Documents Archives, the major repository of documents relating to Poland's industrial and thematic exhibitions, holds documents related to work of the Labour and Payroll Committee, some of which mention the Turin exhibition, while the Warsaw-based Archeology of Photography Foundation hosts a collection of photographs and preparatory drawings which has been crucial for reconstructing the exhibition. The Turin National Archives (Archivio di Stato di Torino) and the Historical Archive of the City of Turin (Archivio Storico della Citta di Torino) contain brief notes about the Polish contribution to the ILE. These archives also hold ILE catalogues, comprehensive guides, promotional brochures and monthly bulletins released by the national committee, along with international press reports, which provide fragmented information about the exhibition's planning, rationale, content and critical reception. What emerges from this incomplete data is an original and multi-layered diplomatic project conceived in the midst of the Cold War, shortly after a period of political upheaval in the Eastern Bloc. This article argues that welfare was an original component of Poland's self-imagining as a socialist, yet distinctly unique, state.

Design Diplomacy

The International Labour Exhibition, from the outset, demonstrated the Turin organisers’ global ambitions.Footnote 5 They first secured the support of both the Italian government and international bodies, including the International Labour Organisation (ILO), before being finally endorsed by the Bureau International des Expositions. As an officially recognised specialist international exhibition, the ILE was obliged to ensure that the main theme had a global outlook and that it would address the broader needs of civilisation.Footnote 6 By following this guidance, the ILE was continuing the tradition of international expositions that promoted collaboration between nations for the benefit of the whole of humanity.

Once the event had attained official status, the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs issued invitations through its official diplomatic channels to the international community. In response, eighteen states from both sides of the Iron Curtain declared their intention to participate: Poland was one of five participants from the Eastern Bloc.Footnote 7 The ILE quickly became a showcase for national achievements that actively avoided raising the question of the situation of the working class.Footnote 8 It also had very little to do with the buoyant narrative of collaboration between nations that the organisers had initially suggested. Instead, the event became a site for cultural diplomacy – or, more specifically, design diplomacy – in the midst of the Cold War.

Cultural diplomacy has been gaining scholarly prominence since the 1990s, when a number of historical studies concerning the diplomatic efforts of the United States during the Cold War were published.Footnote 9 From an investigation of different national case studies throughout the twentieth century, a number of definitions were formulated that aimed to identify this transnational phenomenon by defining the objectives and strategies, the actors and the broader networks involved in cultural diplomatic projects. During this period, cultural diplomacy became conceptualised as an instrument of national policy, devised by states in collaboration with non-governmental actors, including members of artistic milieux, that was intended to shape international public opinion through the creation of a favourable national image. Design diplomacy, a term coined to describe a more specific area of cultural diplomacy, has been employed in practice for many decades but emerged as a subject in historical studies only in the 2000s. It grew from historians’ interest in design as a marker of national identity that various states utilised for their national benefit, whether this was commercial profit or political leverage.Footnote 10 For some researchers the term highlighted the subject at the centre of the diplomatic effort, i.e. the design culture of a particular nation as it was demonstrated through production and consumption, and as it was conceptualised for an international audience.Footnote 11 For others, the term implied the engagement of design professionals in governmental actions in a global context.Footnote 12 Susan Reid has explained design diplomacy as the study of ‘how international relations have been materialized and played out in the multimedia form of international expositions, and, conversely, how the design of such expositions helped shape international relations’.Footnote 13 This paper combines these two approaches to design diplomacy. It demonstrates that by deploying graphic design, exhibition design and the design of modern facilities for public use, the exhibition makers, including a labour policy expert and a team of experienced designers, created ‘a brilliant scenography’ – as Rogers termed it – for presenting the post-Stalinist welfare project of People's Poland. Modern design, however, not only ensured that this idea was communicated in an interesting fashion to an international audience: it also underpinned the humanist premise of the socialist welfare state.

In the post-war period, design emerged as a significant ‘soft power’, a term popularised by Joseph Nye. However, Nye considered that this power was ‘a staple of daily democratic politics’, whereas ‘leaders in authoritarian countries’ relied on coercion in order to achieve their goals.Footnote 14 In the last fifteen years or so this misjudged differentiation between the East and the West, at least on the international front, has been widely challenged by the revelation of the efforts of cultural diplomacy undertaken by the Soviet Union, its republics and other countries from the Eastern Bloc.Footnote 15 These studies have not only proved that soft power was an important component of diplomatic endeavours for regimes on both sides of the Iron Curtain, but have also inspired further research into its specificity, often from the vantage point of broadly understood design. Greg Castillo, for example, compared the ways in which actors from both sides of the political divide used displays of domestic interiors to represent their own ‘culture, values, belief systems, and perceived moral authority’.Footnote 16 His study, among many others, revealed that governments in both blocs often resorted to a similar set of ideas, such as modernisation or consumption, to prove the superiority of their political systems. In this way, national exhibitions functioned as a response or reaction to a proposition that the other side was expected to make.Footnote 17 Although Khrushchev's stated ambition ‘to catch up and overtake' the capitalist West signals the origin of the initial stimulus, this article proposes that it was not always the capitalist West that provided a prompt for this competition.Footnote 18

In Turin, by showcasing the ‘social achievements of People's Poland’ embodied by modern design in the display – architecture for schools, housing, factories and recreation facilities and an animated film – and the design of the display – the spatial arrangement of the Polish section featured photomontage banners – the Polish exhibition articulated the moral authority of socialism.Footnote 19 By doing so, Poland marked its position in what Herbert Obinger and Carina Schmitt called ‘the welfare race’, a competition between the countries and the political blocs that had as their focus the welfare of their respective citizens.Footnote 20 The idea that the Cold War contest concerned not only the well-recognised areas of space conquest, military power or the provision of consumer goods is productive here, for at least two reasons. First, it recognises the existence of the socialist welfare state, a phenomenon that for decades scholars have been extremely cautious and defensive about, as they associated the welfare state with democratic societies.Footnote 21 Second, the term suggests that, over time, both democratic and socialist models of welfare developed their own specific characteristics. Both of these points are highly relevant in the context of the ILE, where different states struggled to manifest their distinctiveness within the thematic frame of technical and social developments in relation to labour.

Historical Premises of the Polish Welfare Project

The Second World War prompted the unprecedented development of the welfare state globally, and the competitive climate of the Cold War made each country consider its own specific approach to social welfare.Footnote 22 While in the West the inclusive and egalitarian approach to social policy resulted from the discourse around the general principles of human behaviour prompted by the United Nations’ 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights, in the East it was underpinned by socialist ideology.Footnote 23 That is not to say that social policies in the Eastern Bloc countries imitated the Soviet model. On the contrary, they were shaped by their respective national expertise and organisational structures that had been developed in the 1920s and 1930s.Footnote 24 All these countries nonetheless shared the ideological premises of the socialist welfare state – full employment and state-subsidised health services, education and housing, which were to be provided equally to all citizens. Over the following decades, as Michael Lebovitz has suggested, they became ‘part of the norms that formed the moral economy of the working class in Real Socialism’.Footnote 25

The Polish welfare state was presented in Turin as an example of a socialist welfare state, yet it should be considered as an outcome of broader historical developments underpinning the relationship between the state and the people. Scholars of modern history, as well as social and political scientists, have already examined the trajectory of the Polish welfare projects from many different perspectives: as part of a comparative study of Central and Eastern Europe; within a nation-specific enquiry that spanned the period from the nineteenth century to the post-socialist period; or as an aspect of research into a specific type of social benefits system and its recipients.Footnote 26 In the context of this article and the deployment of welfare in Poland's diplomatic project, two aspects of this history should be emphasised: the specificity of the welfare system of People's Poland informed by the country's socio-economic profile and welfare reform attempts in the first post-Thaw years.

In October 1956, following a series of workers’ strikes, Władysław Gomułka became the new leader of the Polish Communist Party. To stabilise the situation in the country he made a series of ad hoc changes in social policy. The majority of them focused on workers’ welfare, a strategic decision that was intended to ensure the workers’ support for the new regime. For example, the newly formed workers’ councils were given the authority to manage the organisation of work in a way that resembled the Yugoslavian model of self-management. This gesture raised hopes across Polish society for genuine political change, but these evaporated two years later when the regime curtailed the role of the councils and revoked the workers’ right to political representation.Footnote 27 Gomułka's manoeuvre was one of many instances in which the state used welfare provision to ensure support for its rule. Padraig Kenney has suggested that by prioritising workers employed in strategically important branches of the national economy from the late 1940s onwards, the state was aiming to ensure the stability of the system.Footnote 28 The social reforms were instrumentalised, and were predominantly driven by political and economic rationales, not the real needs of Polish society.

The Polish contribution to the International Labour Exhibition presented the relative growth of social welfare in Gomułka's five years of office in a different light. It emphasised the role of state intervention in the difficult life situations that impacted individuals’ ability to work. By referring to the constitution of the Polish People's Republic it presented social protection as the legal right of every Polish citizen. It also showcased buildings with a social role, namely houses, public schools, workplaces and leisure facilities, which represented the most widespread form of social welfare developed in Poland: state-subsidised accommodation; free, compulsory, universal public education, introduced shortly after the war; full employment and organised holidays. It presented Poland as an examplary socialist welfare state with the strong position of the state and highlighted the breadth of the social welfare programmes it offered. At the same time, the exhibition aimed to demonstrate the specificity of the Polish welfare state that evolved as part of its post-Stalinist modernising project.

Social Achievements versus Technological Advancements

The Polish presentation in Turin was organised by the Labour and Payroll Committee (Komitet Pracy i Płac), a governmental body established in 1960 after the Ministry of Labour and Social Welfare (Ministerstwo Pracy i Opieki Społecznej) was disbanded. This de facto defunct public institution was an unusual commissioner – most of the exhibitions that Poland had previously sent abroad had been overseen by governmental institutions with an overt international agenda, such as the Ministry of Art and Culture (Ministerstwo Kultury i Sztuki), the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (Ministerstwo Spraw Zagranicznych) or the Ministry of International Trade (Ministerstwo Handlu Zagranicznego), or their dependent agencies. Their involvement in devising exhibitions clearly indicated the aims of the Polish presentations – to promote Polish culture, expand exports and develop international alliances. Although not obvious, the Committee's involvement with the ILE could also be explained through external obligations, which included the ‘exchange of information, experiences, experts and grants’ with foreign institutions such as the International Labour Organisation.Footnote 29 Therefore, although it was not a diplomatic institution as such, in Turin the Committee had a diplomatic mission to fulfil.

Jerzy Licki (Jerzy Finkelkraut), a leading labour scholar and experienced public servant, was responsible for this project as commissar of the Polish exhibition. Educated in the early 1920s, Licki belonged to an influential milieu of Polish sociologists in the early days of the discipline. Alongside his prolific academic career, he was involved in several initiatives related to social law, including acting as Poland's representative at the annual International Labour Organisation conferences. His expertise led him to the Ministry of Labour and Social Policy (Ministerstwo Pracy i Opieki Społecznej), where he was employed in various roles in the decades that followed.Footnote 30 His professional pathway confirms what some scholars considered the most important aspect of the formation of the social welfare system in the post-war societies that were under Moscow's influence. Mojca Novak, for example, suggests that the greatest impact on the development of social policy in Eastern Europe was ‘not the current structure of welfare state institutions, but which actors (meaning the elite and groups) and factors’ were involved in the process.Footnote 31 Like many other civil servants, intellectuals and academics who began their careers in the inter-war period, Licki is a good example of this trans-systemic legacy. From the mid-1950s, after a period of Stalinist persecutions, the state turned to the expertise of these groups to establish new national policies and institutional structures. The approach of welfare experts such as Licki was more technocratic than ideological, and this made the transfer of their expertise between the systems feasible. This does not mean their work was not politicised; on the contrary, it was deeply embedded in the contemporary political agenda.

A decade earlier, Licki, together with Eugenia Pragierowa, a lawyer and member of parliament, had authored a booklet, Ten Years of People's Poland, which praised the social achievements of the Polish state from the moment ‘when the working class took power’.Footnote 32 Despite the enduring legacy of the inter-war developments – which both Licki and Pragierowa were part of – the text presented the current system of social welfare as the outcome of post-war political transformation. It argued that whereas the inter-war governments had been incapable of resolving issues such as unemployment, the provision of wide access to education, the securing of women's right to work and the ensuring of safety in the workplace (the text described them as incapable, negligent and incompetent at handling social issues), the post-war socialist state had already begun a social transformation.

This comparative narrative between the inter- and post-war periods reverberated in the synopsis of the Polish exhibition published in the ILE catalogue, that was probably written by Licki. The text outlined the rationale and legal foundation of the support that the state provided to those whose capacity to earn a living had been affected. It claimed that the socialist state protected ‘working people against complete or partial loss of work, the source of their livelihood’, which was caused by old age, maternity, illness or injury, or the loss of the family breadwinner.Footnote 33 While it was written into the constitution of People's Poland that employment was a ‘right, obligation and a matter of honour of every citizen’, in these extreme circumstances, when someone became destitute, the state acknowledged its responsibility to step in with help.Footnote 34 The socialist state, the catalogue recounted, following ‘the demands of the working people and their struggles for partial or complete protection’, developed appropriate policies that aimed to support affected individuals.Footnote 35 The social programme, as the text further elaborated, constituted a ‘social reply’, the evidence of which was represented on the large white curved walls of the Polish exhibition. Although the text did not mention any actual policy, it recalled that each ‘reply’ was guaranteed by the constitution, relevant excerpts of which were displayed across specific sections. These responses were presented against a visual representation of life circumstances that threatened an individual's ability to work, such as emigration, illness, maternity, disability and old age. In this way, ‘The symbol of the “negative” or “evil” is answered in each case by the “positive”, – the “reply” illustrating the means of easing the ensuing evil or removing its basis’.Footnote 36

The relationship between labour and social policy was also highlighted by other participants from behind the Iron Curtain, who emphasised the significance of the working class to their national economy and cultural life. The Hungarian exhibition showed ‘the relationship between man and work in a society building socialism’, exemplified by the products of the country's manual labour, from crafts to precision manufacturing.Footnote 37 Romania focused on the post-war development of its petrochemical industry, including the ‘evolution of working conditions, and the living standard of oil workers, some aspects of the new towns, dwellings, canteens, hospitals, nurseries, sports grounds’.Footnote 38 Czechoslovakia provided a celebratory account of advances in cooperative agriculture over the previous century, with special insights into ‘the material and cultural welfare of the cooperative farmers’.Footnote 39 The Soviet Union's exhibition, which not only occupied the most space among the Eastern European participants but was also one of the biggest national exhibits in the Palazzo del Lavoro, focused on the improvement of the working environment and its impact on workers’ efficiency and wellbeing. The Soviet exhibition's slogan, ‘Everything for the good of man’, underlined the benefits that citizens were guaranteed by its constitution: ‘right to work, to rest, to education, right to assistance in old age and in the case of inability to work’.Footnote 40 The exhibition presented aspects of everyday life, such as consumption, healthcare and recreation, which had been improved through the development of ‘holidays, rest-houses, tourism and sport’. It also incorporated the recent success of the Soviet space programme – just a few weeks earlier, cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin had successfully completed his journey into outer space – and portrayed it as the country's victory over the United States in the space race.

Even a quick glimpse of these extracts from the curatorial statements reveals that all the Eastern European participants shared a narrative about the state's care for the wellbeing of workers. On the other hand, the narrative that permeated most of the Western countries’ exhibits was entirely different, focusing instead on their technological capabilities in the context of modern labour. The United States, for instance, presented an early computer and demonstrated its use for communication not only between countries but also with outer space, while the United Kingdom proudly declared that their scientific research could and would advance modern society. Many international organisations present in Turin pursued similar technological ideals in their own exhibits, demonstrating their belief that modern technology could improve the working conditions of people across the globe. For example, the exhibition prepared by the Organisation for European Economic Co-operation promoted ‘co-operative efforts to place science and technology at the service of men, to fit the worker to his job and the job to the worker’.Footnote 41 The International Labour Organisation more cautiously asserted that although modern machinery had significantly improved working conditions, ‘new techniques create new problems’.Footnote 42

The Italian organisers sympathised with both the worker-centred and the techno-determinist messages that the East and the West respectively were projecting to the world through their exhibitions. In the words of the Italian governmental commissioner, Giustino Arpesani, the ILE aimed to ‘re-establish the dignity of workers and to emphasise their constant need of support, legal protection and the continuous development of social justice’.Footnote 43 On the other hand, the ILE committee heralded modern technology as having ‘true power and importance, something which is given to the service of man and a great tool which man himself has created and uses at will to organize the material conditions of his future existence according to a noble and reasonable ideal’.Footnote 44 By doing so, the ILE followed the tradition of many post-war world fairs, which celebrated modern science as a means for achieving global peace and prosperity.Footnote 45

While the organisers intended their declarations to consolidate these two sentiments, as the title of the ILE suggested, the transformative potential of technology in the context of modern labour was clearly aligned with the narratives of the Western participants. The Soviet Union, with the presentation of its space exploration programme, was a notable exception. Poland and other Eastern European countries relied on the presentation of social welfare, provided by strong protective states, to manifest their contribution to the debate about labour conditions. This does not mean that the Polish government entirely disregarded modern technology and its role in the organisation of work and the everyday life of working people. Indeed, the regime's interest in advanced technologies increased a few years later, underlined by programmes of industrial reforms and economic policies under Gomułka and Gierek.Footnote 46 In the early 1960s, the Polish authorities, however, still felt much more confident about building their international presence by projecting their social, rather than their technological, credentials, especially as it was clear that the capitalist West was incapable of providing equally extensive welfare support for its citizens.

Post-Thaw Humanism and the Protective State

The Polish exhibits included no physical objects; instead, the entire show was conceived around enlarged photographs, illustrations, informative panels and an animated film played on a loop. While the written statement in the exhibition catalogue briefly presented the rationale of the Polish welfare state, the exhibition design translated the principles of the socialist welfare state into a comprehensive visual story (Figures 1 and 2).

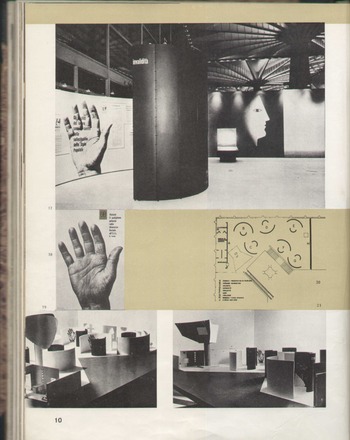

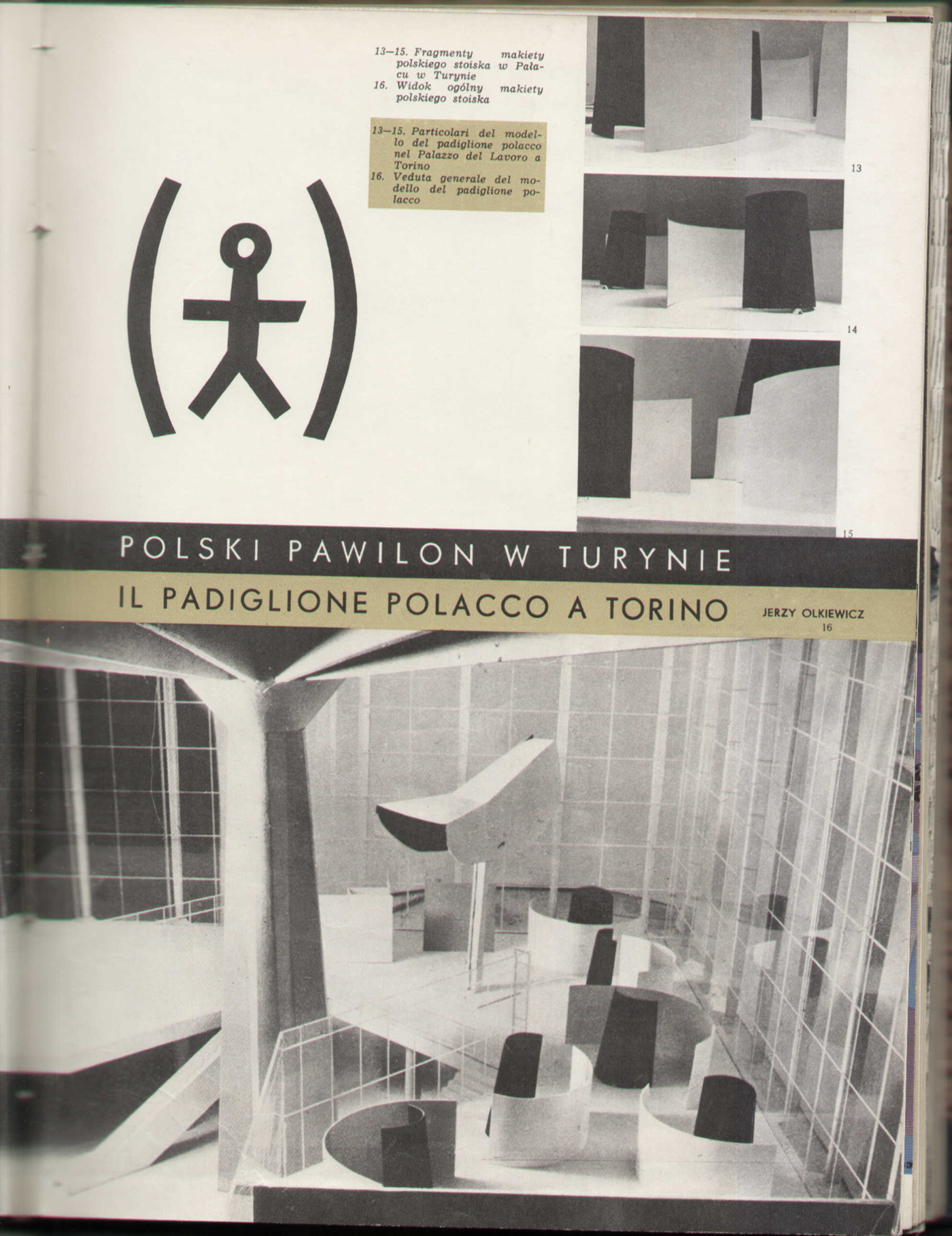

Figure 1. A spreadsheet of Projekt magazine featuring images from the Polish pavilion at the International Labour Exhibition in Turin. ‘Polski Pawilon w Turynie’, Projekt, 6, 3 (1961), 10.

Figure 2. A spreadsheet of Projekt magazine featuring images from the Polish pavilion at the International Labour Exhibition in Turin. ‘Polski Pawilon w Turynie’, Projekt, 6, 3 (1961), 11.

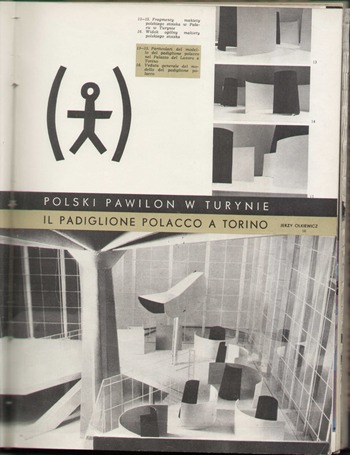

The exhibition was conceived by a team of the most prolific graphic designers working in Poland at the time – Wojciech Zamecznik, Wojciech Fangor, Jan Lenica, Józef Mroszczak, Julian Pałka and Henryk Tomaszewski – in collaboration with the architect Kazimierz Husarski. These were internationally acclaimed artists associated with the Polish School of Posters, but additionally they – often collaboratively – had designed numerous exhibitions on national industry, agriculture, art and craft that Poland had presented around the world. This part of their practice, although prolific, was less known to their contemporaries (and scholars alike), and it was rarely publicly attributed. Their designs for exhibitions included both spatial arrangements and graphic design, and were characterised by a ‘painterly and semantically complex’ language similar to that found in their posters and printed works.Footnote 47 In Turin, this unique quality not only allowed them to communicate political ideas about the country's social achievements in an attractive form, but also, as the following part of this article will demonstrate, added another level to the interpretation of the exhibit's overall theme. The exhibition logo acted as a prelude to the metaphorical imagery that the Polish exhibit explored. A simplified human silhouette placed within parentheses was an ingenious representation of the Polish welfare state: the brackets shielded the figure from external danger and symbolised the state's custodianship of its citizens. The logo, in a concise way, summarised the relationship between the citizen and the state, which assumed paternal responsibilities for vulnerable individuals with the promise to protect them against the evils of the contemporary world.Footnote 48

Set out on one of the mezzanines of the Palazzo del Lavoro, the Polish exhibition opened with an animated film that was displayed above the entrance. This ‘modern medium’, as the text in the catalogue explained, offered visitors ‘a more accurate apprehension of the subject’.Footnote 49 A more formal introduction to the theme was provided by the introductory panel that visitors saw when they entered the Polish section. It traced the historical origins of the Polish welfare system and linked them with the expansion of the labour movement in the post-war period. The opposite wall, which was conceived as the closing component of the narrative, offered remarks about the future of welfare. This section expressed ‘faith in the realization of social justice, based on lasting peace, and lasting peace based on social justice’.Footnote 50 It included large decorative panels in red and white – Poland's national colours – featuring paintings with the blurred contours characteristic of Wojciech Fangor's style. While little is known about these sections of the Polish exhibition, the documentation of the main part provides a better insight into how it looked. It consisted of concave partitions that divided the space into six differently themed sections, which organised the exhibition in spatial, but also narrative, terms. The walls, repeating the curvature of the brackets, turned the Polish exhibit into a three-dimensional interpretation of the exhibition logo. Each section addressed one specific social issue that was considered in two parts: a black wall presented the problem, while a white wall outlined the solution.Footnote 51 Colourful photographs of modern architecture demonstrated the state's achievement in the fields of housing, education and health provision. The exhibit closed with a small library with books and brochures about social and welfare services in socialist Poland that enabled the visitor to learn about the exhibition's themes in greater depth.

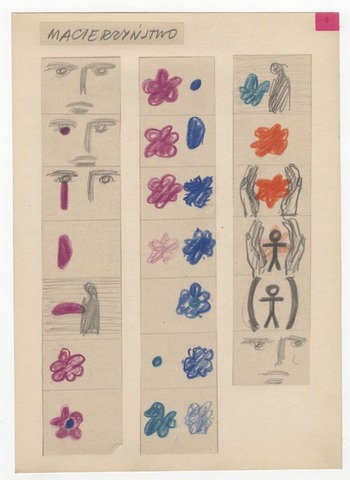

The dominant visual motif of the exhibition was that of the hand. Cupped hands, which served as a metaphor for the paternalistic state, appeared in the initial concept drawings (Figure 3) of the exhibition logo and were later replaced with parentheses. Enlarged black-and-white photographs of an open palm were displayed on the rounded walls. Here, too, the hand symbolised the protection of a socialist state – its legal foundations were outlined in the fragments of the Polish constitution that were printed over every photograph, ‘illustrating the means of easing the ensuing evil or removing its basis’.Footnote 52 The same image of a hand was repeated in Italia 61, an animated film created by Wojciech Zamecznik and Jan Lenica that was screened at the entrance to the Polish section. While many other participants used films to entertain audiences and deliver an optimistic message about their country's latest achievements, the Polish film was far from cheerful.Footnote 53 It was composed of a stream of photomontages that portrayed transformative moments in human life, such as unemployment, emigration, war, sickness, old age and maternity.Footnote 54 The visual vignettes dissolved into each other to the rhythm of a soundtrack composed by the pioneer of musique concrète in Poland, Andrzej Markowski.Footnote 55 As one Polish journalist recounted:

A human face, its transformation into ruins and its reappearance with eyes shut, a red teardrop rolling down from them – that's war. A hand that moves and then all of a sudden is lifeless – that's unemployment. Emigration is shown as the transfiguration of a human face into a white bird flowing through red streaks, then a black bird, etc.Footnote 56

Figure 3. An early version of the storyboard for the animated film Italia 61 by Wojciech Zamecznik and Jan Lenica. Courtesy of J. & S. Zamecznik/Archeology of Photography Foundation.

In contrast to its use in the logo or on the walls, the hand here symbolised not the state but the human – or more precisely, the worker's – body, and its exposure to numerous physical and psychological challenges. The meaning of the hand – whether it referred to the worker or the state – and what it represented – labour or protection – shifted continually throughout the exhibition. The original contexts of the photographs that Zamecznik and Lenica reused in their designs for Turin deepened this visual narrative further.

To create this visually compelling story, Zamecznik and Lenica used reproductions of existing photographs, some of which can be identified.Footnote 57 The main photograph of a hand that appeared in many configurations in the design of the Polish exhibition was taken by a Swiss photographer, Ernst Koehli. It was part of a series of hand studies that Koehli produced between the 1930s and the 1950s while working on a commission to document the labour movement in Switzerland. Little is known about the photographer himself, but his photos were widely reproduced in international photographic journals of the time, which is where the designers of the Polish exhibition had encountered them.Footnote 58 Zamecznik and Lenica also found inspiration in photographs of hands by a Polish photographer associated with the Lvov cultural circle, Janina Mierzecka. Best known for her early pictorial portraits, in her later work Mierzecka pursued an entirely different aesthetic, that had much in common with the ‘new objectivity’ that was being explored at that time by German artists.Footnote 59 The hand studies that she developed from 1925 to the 1930s, which had drawn Zamecznik's and Lenica's interest, originated as a series of illustrations for a research project on the impact of labour conditions on human skin, undertaken by Mierzecka's husband, a well-known dermatologist.Footnote 60 They were published in an illustrated anatomical atlas with the title The Working Hand, but soon attracted the attention of critics, who were drawn to their artistic value.Footnote 61

The studies by both Koehli and Mierzecka featured the hands of workers in heavy industry. The high contrast used in these photographs accentuated the roughness of the skin, a map of deep furrows marked by years of manual labour. These were intimate portraits of the working class that did not present strong silhouettes of workers in heroic poses but instead focused on body fragments that exposed their fragility and weariness. This compassionate imagery of the working class suggested a shift away from celebrating productivity towards embracing a humanist approach. In Turin, the workers were portrayed not as heroes whose labour was contributing to the reconstruction of the Polish industry or the development of the socialist economy, but as vulnerable human beings.

The use of work by American photographers Russell Lee, Elliott Erwitt, Robert Mottar and Wayne F. Miller further accentuated the humanist undertones of the presentation of the Polish welfare system. The designers probably encountered these images in the landmark exhibition The Family of Man, curated by Edward Steichen for the New York Museum of Modern Art in 1955. Following an enthusiastic reception in New York, and thanks to the support of the United States Information Agency (USIA), the exhibition then toured internationally, this time as part of an American cultural diplomacy project that aimed to promote national values in the midst of the Cold War. Over the next decade it was shown in forty-eight countries across the world, and in 1959 the exhibition came to Poland, where it was shown in seven different locations.Footnote 62 The most prestigious Polish exhibition venue was Warsaw's National Theatre, for which Wojciech Zamecznik designed the poster and his cousin Stanisław the spatial arrangement.Footnote 63

In their design for Turin, Zamecznik and Lenica not only used some of the works from the American exhibition in their photomontages, but also echoed the narrative proposed by Steichen. It evolved around a belief in shared human experience. Over 500 photographs from 68 countries collectively reflected, as Steichen noted, ‘the universal elements and emotions in the everydayness of life’.Footnote 64 This focus on the universal aspects of human existence was reiterated in the visual narrative of the Polish exhibition. The animated film portrayed transformative moments in human life without locating them in any particular geography or political system. A limited use of script and a focus on abstract imagery made the film particularly suitable for international screenings, but also allowed viewers to identify with the figures whose fate it captured. The film and the exhibits conceived for a diplomatic purpose were to represent the values and ideas of the Polish state. Paradoxically, then, Zamecznik and Lenica reused the American photographs displayed in The Family of Man to tell a story about working people's rights in socialist Poland; through this process ‘the sentimental humanism’ of the American show was remodelled into ‘Thaw humanism’.Footnote 65

This interest in the human condition and the desire to capture the universal dimension of human life was shared by intellectuals worldwide, for whom humanism was a tenet of many philosophical, artistic and political projects.Footnote 66 It was, for the most part, a reaction to the atrocities of the Second World War and the resulting post-war trauma. In the Eastern Europe of the mid-1950s, it emerged as an intellectual current against the strictures of the Stalinist system. On the wave of the political Thaw, intellectuals – including designers, architects, writers and filmmakers – adopted a humanist approach in their work to articulate the subjectivity of the individual as opposed to the spirit of collectivism that was sanctioned by the doctrine of socialist realism in the early 1950s.Footnote 67 Zamecznik's earlier photographic works, which often captured the everyday life of the street or his own domestic setting, manifested ‘a particular type of humanism, oriented towards the structure of the individual and his/her sensual and emotional experiences’.Footnote 68 Lenica's observation skills originated from his early work as a cartoonist and as he moved into more comprehensive projects evolved into, as one reviewer pointed out, ‘a profound interest in the problems of a human being who is lost in the mechanisms of contemporaneity […] the battle against evil and human harm, ignorance and the loss of humanity between the cogs of the machine of militarism, fascism and bureaucracy’.Footnote 69 In Turin, both designers drew from their earlier experiences as they juxtaposed the universal imagery of human misfortune with the specific ‘responses’ offered by the state. This narrative gradually unfolded for the exhibition's visitors as they moved through the space – the animated film portrayed personal tragedies, exhibition panels outlined the ideological and legislative foundation of the state's response, and the photographs of modern architecture for public use served as material evidence of the social system that was in place in socialist Poland.

The Tangible Examples of the Social Securities

The exhibition featured housing estates, educational facilities, factories and holiday resorts, which were types of buildings that constituted what some scholars have called ‘the built reality of welfare state policies’.Footnote 70 These examples of mid-century architectural modernism that emerged in Poland after the political Thaw created the physical conditions for the implementation of the Gomułka's regime's social policies. Additionally, as various scholars have shown, the wide adaptation of the Modernist style in architecture for social building projects across Europe was driven by the development of the welfare state itself.Footnote 71

Social housing, despite being widely promoted by states across the political divide to exemplify their welfare credentials, occupied only a small part of the Polish exhibition in Turin.Footnote 72 The exhibition featured newly completed housing estates in Gdańsk and Tarnobrzeg, a city in south-eastern Poland that had grown exponentially with the expansion of sulphur mining in the 1950s.Footnote 73 Both estates, which included housing, nurseries, schools, canteens, sports clubs and other facilities for workers in the local industry and their families, were presented in the context of a wider transformation of Polish industry, which drove the development of towns around new industrial hubs. The application of standardised solutions – introduced in the late 1950s, almost a decade later than in Czechoslovakia and East Germany – increased the spread of these projects.Footnote 74 Thanks to the changes in the official building regulations during the first five years of Gomułka's regime, the number of available apartments increased from 90,800 in 1956 to 144,200 in 1961.Footnote 75

The late 1950s and early 1960s saw a spectacular expansion of an educational infrastructure that was triggered by demographic growth and educational reform, embedded in a political narrative. Free, compulsory, universal public education, introduced shortly after the war, was one of the most important social achievements of the socialist state, and the modern design of educational facilities in Poland, as one architectural commentator suggested, reflected the egalitarian nature of the Polish education system.Footnote 76 The exhibition featured a small selection of these projects, including primary schools in Warsaw's Bielany district and in Nowe Tychy, a new industrial town in southern Poland.Footnote 77 These ‘schools of the future’, as they were dubbed in the state propaganda, followed the same architectural model of a two- or three-storey building constructed with prefabricated components. Built en masse as part of the Millennium initiative, they constituted the state's response to the Catholic Church's celebration of the 1000th anniversary of the establishment of the first Polish nation, marked by the Christianization of Poland.Footnote 78 While the Church placed special emphasis on engaging with society – and youth in particular – on a spiritual plane, the Party addressed the educational needs of the younger generation. At the end of the programme, which lasted nearly fifteen years, over 1,400 new schools had been built. The state promoted these new facilities, that were largely financed by public contributions, as a testament to the regime's commitment to eliminating illiteracy and ensuring social mobility through education.Footnote 79

The textile factories in western and central Poland that featured in Turin not only represented the country's post-war industrialisation but also drew attention to an important shift towards light industry.Footnote 80 In the late 1950s, following a change in economic priorities, textiles became a leading element of Polish exports to the Soviet Union and other Eastern European countries.Footnote 81 In response to the growing demands for Polish products new plants were built, and existing factories were significantly expanded and modernised. State-of-the-art technologies, often bought abroad, were deployed to ensure production efficiency – ‘one weaver operates 1100 spindles which equals [the amount of work performed by] 1100 of our grandmothers [working with] spinning wheels’, as a newsreel from Kalisz reported.Footnote 82 The new industrial architecture was a frequent subject of photo essays published in popular magazines such as Polska, an illustrated monthly issued in several European languages, and in the design periodical Projekt. Journalists not only applauded their aesthetic and functional qualities, but also recognised them as a sign that the state was embracing the potential of design in the battle to improve labour productivity and organisation.Footnote 83 The Kalisz factory, mentioned in one of these articles and featured at the exhibition in Turin, was a pioneering example of this approach. Its design was informed by advancements in technology and the application of new materials, such as reinforced concrete, but it also benefited from interdisciplinary collaboration between architects, construction engineers and artists, who worked on the official state commission. In turn, thoughtfully designed factory interiors reportedly improved workers’ health and safety and boosted their spirits.Footnote 84 In fact, the impact of design on workers’ wellbeing and the organisation of labour in the early 1960s attracted the interest of the wider Polish design community. For example, the designer and educator Andrzej Pawłowski, who championed the professionalisation of the discipline in Poland, argued that one of the major tasks of an artist working with industry – or, as he put it, a ‘designer of industrial forms’ – should involve designing tools, the means of production and factories.Footnote 85

The state investment in workers’ health and wellbeing through modern design was even more pronounced in health resorts and holiday facilities. This was a relatively new category of amenities that developed steadily from the 1950s onwards to cater for the needs of workers and their families. As their popularity grew, the state used them to support the official narrative of socialist consumption.Footnote 86 The exhibition featured The Steelworker (Hutnik), a mountain spa in Szczawnica in southern Poland designed by Zofia Fedyk and Jerzy Nowicki and completed in 1960. The material qualities of this and other similar facilities constituted part of the narrative of the socialist welfare state. While the prefabricated technology and reinforced concrete enabled high occupancy and suggested the wide availability of the state-subsidised holiday, the artistic decoration, such as the mosaics, added a human touch to these high-rise buildings while referencing the state's artistic patronage. The health resorts and holiday facilities were, as Diane P. Koenker suggested, ‘workshops for the repair of toilers’, and holidays there were considered as a reward for the good work that the workers performed for the rest of the year.Footnote 87 As access to these facilities was offered primarily to employees of strategically important industries, these facilities demonstrated the entanglement of economic and social policies, and between labour and leisure in the socialist system.Footnote 88

The modern buildings were, as one commentator noted, ‘tangible examples of the social securities’.Footnote 89 By displaying them within the symbolic arrangement of the exhibit space, the Polish organisers intended to visualise the state's paternalistic care of its workers by ensuring their protection, wellbeing and personal growth. Despite these efforts, the exhibition failed to mobilise the imagination of the international critics, perhaps understandably – Poland's was just a small display, competing for audiences’ attention with the other ILE exhibits and the grandiose programmes of events, such as the commemoration of Italy's unification, which included, amongst other events, a flower display, many fashion catwalk shows, a Leonardo da Vinci retrospective exhibition and an exhibition of historical photography.Footnote 90 Reviewers mentioned the Polish exhibition only in passing, barely acknowledging the country's presence and its main focus, meaning that Poland's diplomatic effort was to little avail.

Most critics applauded the skilful use of exhibition design across the ILE, while noting that it turned the exhibition into a ‘sort of painless pedagogy’.Footnote 91 Each country used visual means to communicate their latest social achievements, and the flamboyance of these aesthetic solutions overcame the messages themselves. British journalist Peter Rawstorne, who reviewed the exhibition for the magazine The Spectator, noted that these design strategies were largely aimed at attracting an international audience in order to project an impression of national superiority in comparison with other exhibits. For the purposes of propaganda, he reported, ‘the skill of the international designers has been stretched to its limit’.Footnote 92 It was indeed a testament to design diplomacy at work. Modern aesthetics dominated the majority of the national displays, which used bold typography, film projections and clear spatial layouts to offer an imaginative interpretation of their selected theme. Different exhibits made use of state-of-the-art technology to provide visitors with entertainment, but still, as a journalist from The Economist suggested, the whole event called ‘for an elevated frame of mind and an uncomfortable degree of concentration’.Footnote 93 The exhibition as a whole reportedly revealed a bias towards an educated audience who were able to understand and appreciate its Modernist aesthetics. The sophisticated visual language made it inaccessible to many working-class visitors, whose contribution to the development of both Italy and the modern world the event was intended to celebrate. A journalist writing for Turin's daily newspaper, Gazzetta Del Popolo, suggested that its abundant symbolism and tendency towards synthesis made the exhibition ‘a bit murky to an “untrained” visitor’.Footnote 94

All of these comments were equally applicable to the Polish section, which presented design and architecture as a far-fetched metaphor for the promise of equality and a secure life under the socialist system. The highly symbolic language of the Polish exhibition appealed predominantly to Italian intellectuals who, as a Polish journalist reporting for the official daily Dziennik Polski noted, appreciated its ‘modern, elegant and succinct style’.Footnote 95 In this context, one element of the Polish exhibition appears to have been more successful in conveying the message about social welfare provided by the socialist state – the exhibition logo, which some of the reviews reprinted. This image of ‘the protected little man of Poland' (l'omino protteto della Polonia), as one People's Gazette (Gazzetta Del Popolo) journalist described it, aptly captured the essence of the Polish exhibit.Footnote 96 Despite the lukewarm critical reception to the Polish exhibit, this symbol proved to be effective in working towards a diplomatic goal by encapsulating a complex political idea in a simple sign.

Conclusion

The Polish display in Turin, like many other exhibitions before and after it, testified to an incompatibility between the ideas on display and the everyday living conditions of the nation. The regime's declaration of its breadth of coverage and provision for basic needs was a promise that was never entirely fulfilled.Footnote 97 During the period of ‘real socialism’, not only did the quality of benefits fail to respond to demand; many citizens also remained ineligible for state support. Despite the apparently egalitarian nature of socialism, the state prioritised some occupational groups over others, which resulted in the development of a system of privileges and social hierarchy. The International Labour Exhibition, with its celebratory character, was not the place for claims about Poland's social credentials to be scrutinised in regard to the restriction of personal liberties, nor would the discrepancy between the real and the imagined be challenged, or the actual situation of the working population critically addressed. Nonetheless, the Polish exhibition, by presenting a vision of a strong, compassionate state whose actions were driven by ideological principles rather than economic profit, put forward an alternative model, which is perhaps more thought-provoking today than it would have been in the midst of the Cold War.

The Polish political authorities instrumentalised the concept of the welfare state for decades to gain legitimacy in the eyes of the workers, to manifest its political aspirations and to foreground large ideological projects. This article demonstrates another use of the welfare state project beyond the domestic setting, one in which what was at stake was a battle for the hearts and minds of international public opinion. Rather than resorting to statistics and detailed descriptions of what Polish social policies consisted of following the post-Stalinist reforms, the exhibition employed bold symbolic visual language to emphasise the universal human need for security and protection. The photographic representations of modern architectural projects provided evidence of the welfare system in situ, and by doing so they demonstrated precisely what, according to Rogers, the Italian exhibit had failed to manifest: the state's engagement with modern design to improve the everyday life of working people.

By focusing on the Polish national exhibit and locating it within the broader historical context of Cold War rivalry, this article intends to make two points. First, the text demonstrates that socialist countries like Poland actively sought ways of presenting themselves vis-à-vis other nations. In these efforts, they tried to avoid the comparative blueprint that had been established around the provision of consumer goods or pioneering technology, which from the outset favoured capitalist countries. The socialist welfare project, and in particular its humanistic dimension, largely unparalleled in the West, offered a promising, decentring narrative. Whether the state considered the decision to turn towards social policy as a mark of the country's originality as part of a long-term strategy, and the implications this had in terms of benefit for the nation, remains beyond the scope of this article. Instead, what this article proposes is that the Polish exhibition in Turin makes a case for expanding our understanding of cultural diplomacy and its subject. Second, the article intends to foreground the role of designers as important stakeholders in state diplomatic projects by demonstrating that they actively shaped the country's self-image abroad, often surpassing the official narrative. By recognising designers’ agency, this article further problematises the relationship between socialist state power and creative milieux and broadens its existing literary, cinematographic, fine arts or architectural focus by considering a new professional group. I argue that the very fact that design and designers became indispensable for various national projects in the second part of the twentieth century in turn foregrounds the debate about the role of design diplomacy as a specific aspect of cultural diplomacy.

Acknowledgements

I presented an early version of this article at the welfare state workshop at the University of Oxford in 2020 and I would like to thank my co-convenor, Alessandro Iandolo, and all participants for their useful feedback. I am grateful to the anonymous reviewers and the editor of Contemporary European History for their insightful comments and support in preparing this article.